Guest blog by Kristy M. McAndrew, Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University

Spread of non-native species is a facet of global change that is an unintended consequence of the modern global trade network. Despite efforts put in place to limit such transport, such as International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs), unintentional spread of species continues, and thus, an important part of forest health research and management includes non-native monitoring and control efforts. As other aspects of global change, such as climate and weather patterns, shift, the dynamics between native landscapes and introduced pests may unexpectedly shift as well. For example, increased climate stress of tree hosts may weaken tree defenses, allowing species that historically have not been pests of concern to reach pest status.

Japanese cedar longhorned beetle (Callidiellum rufipenne; JCLB) is a wood boring beetle in the longhorned beetle family, Cerambycidae. The adults are reddish brown in color, and relatively small for longhorned beetles, at only around 1 cm in length. Japanese cedar longhorned beetle has a long history of establishing outside of its native range but has largely been considered a non-issue. It has long been disregarded as a pest because it feeds primarily on dead or dying trees in both the native and invaded ranges. However, there are more examples of these beetles feeding on stressed, but alive, trees in North America. Therefore, I think it is an important insect to take a closer look at.

Life cycle

These beetles have a one-year life cycle, most of which is spent inside a host tree. Adults emerge from host trees in the early spring and seek out other adults to mate with and trees to lay eggs on. Eggs are laid on thin parts of bark or in bark crevices, and when the eggs hatch larvae chew beneath the bark where they feed on the phloem until they have completed larval development. Once larvae are fully developed, they burrow further into the tree, into the xylem tissue, where they pupate, overwinter as fully formed adults, and continue the cycle the following spring.

Native range

The native range of JCLB is eastern Asia. It is common throughout the Korean peninsula and across the islands of Japan. It is also considered native to Eastern China and Russia. Within the native range JCLB is found primarily on dead and/or dying trees and is thus considered a secondary pest. On dead trees they can be found on any diameter of dead woody material, but on declining trees they will likely be in the small diameter branches and stems.

Invasion history

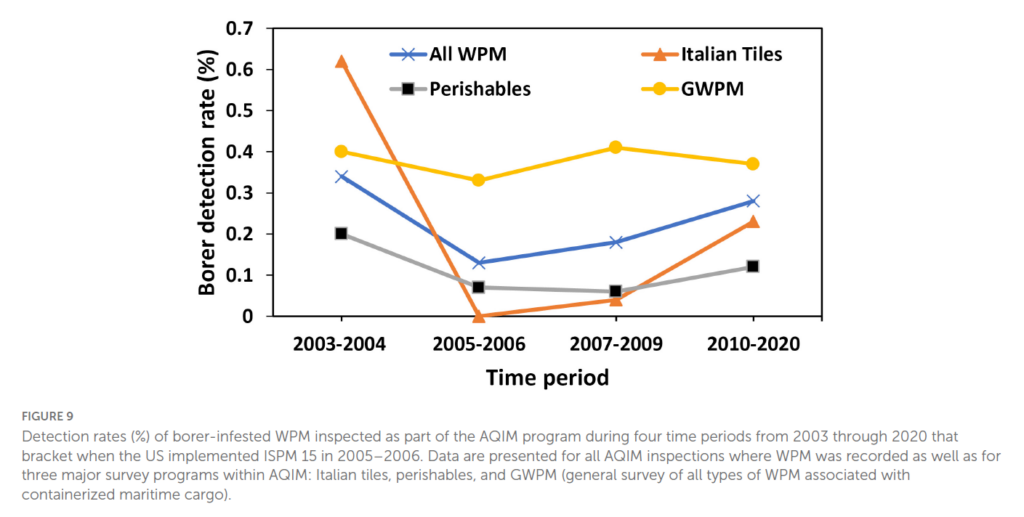

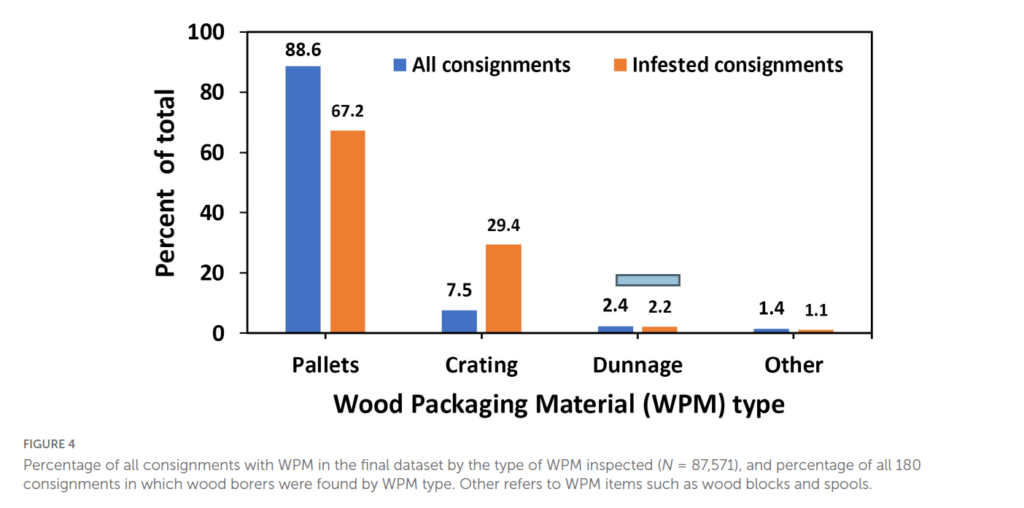

Japanese cedar longhorned beetle was first documented as an invasive pest in the early 1900s in France, and since then has established in at least fifteen countries (Clément 2023). Most of these countries are in Europe, but the United States and Argentina also have established populations. As with most woodboring insects, the invasion pathway is believed to have been wood packaging material being transported via global trade routes. Between 1914 and 2022 it was intercepted over 700 times (reviewed by KM). Since the implementation of ISPM No. 15, only six interceptions have been reported up to 2022 (USDA APHIS data reviewed by K.M.). [For Faith’s view on the regulation of wood packaging, see Fading Forests II and III (links provided at the end of this blog) and earlier blogs posted here under the category “wood packaging”. esp. 1 from 2015].

A USDA risk assessment completed in 2000 suggested other possible pathways of introduction, including balled nursery stock, green logs, and pruned branches (USDA APHIS and Forest Service, 2000).

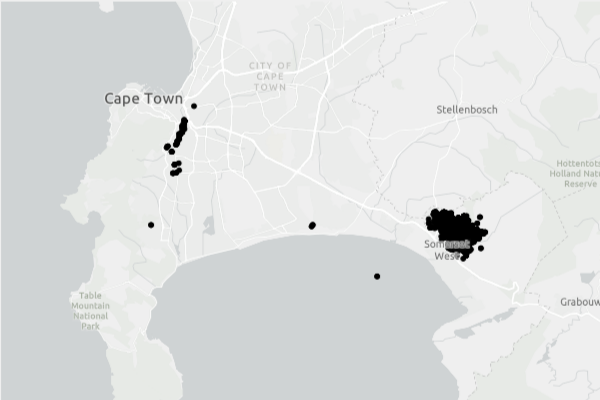

In terms of establishments in North America, JCLB was first detected in natural forests in North Carolina in 1997. It was soon discovered in Connecticut in 1998; in neighboring New York in 1999; and in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island in 2000. It was quickly discovered feeding on live arborvitae (also called northern white cedar; Thuja occidentalis) in these invaded regions. JCLB has since been found in Pennsylvania (in 2010) and Maryland (in 2011). It is important to note that it is not clear when this species truly established, because of its previously discussed long history of being intercepted in ports of entry.

Most introduced populations of JCLB are found in either dead hosts or in the damaged/dead limbs of live hosts. In Buenos Aires, for example, storm-damaged trees with broken limbs are often where beetles are collected (Turienzo 2007). In the United States, eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) and common juniper (Juniperus communis ) are the two native species most commonly affected, but so far there is no evidence of live trees of these species being infested (Maier 2007). However, a growing concern in the United States is that JCLB has been documented on live trees – particularly in urban environments. These trees are typically arborvitae, and they are typically stressed urban trees that have been overwatered and often show signs and symptoms of other health issues.

Host breadth

The host breadth of JCLB encompasses much of the family Cupressaceae. Maier (2007) identified 19 potential hosts from the literature and research, with the vast majority (14) of the hosts being Cupressaceae species, which is indicative of JCLB being a relative generalist, especially when considering species in the cypress family. This is important, because there are over 130 species within Cupressaceae worldwide that could be suitable hosts for JCLB, meaning host will not be a limiting factor in many invasion scenarios for this insect. Most often trees infested by JCLB need to be either stressed or dead, which limits suitability to an extent. However, many landscape trees are inherently stressed, whether it be from a history of roots being balled and wrapped in burlap, being planted in less than ideal scenarios, or being overwatered.

A few reports from research in Japan record JCLB feeding on plants in Pinaceae, primarily Pinus and Abies species. One article reports use of Larix kaempferi; another documented JCLB on the Taxaceae species, Taxus cuspidata. North American pine (Pinus spp.) and fir (Abies spp.) species have not been tested, but if they are revealed as suitable that would increase the availability of hosts in North America significantly.

In southern New England at least nine species have been confirmed as suitable, all of which are in the family Cupressaceae. Native and abundant junipers, such as Juniperus virginiana, appear to be highly suitable hosts. Additional host testing would be beneficial – especially Cupressaceae species that are either threatened or have a limited range. Within the United States there are a total of 28 native Cupressaceae species. Thus the suitable range (in terms of hosts) covers the entire Eastern half of North America through central Texas, most of the Pacific Coast, and widespread but spotty/disjunct areas throughout the Intermountain West and High Plains regions.

Suitability

Tools such as environmental niche models can give helpful estimates of suitability. For species that are typically secondary pests, such as JCLB, it can be difficult to obtain non-biased data with good coverage to make reliable predictions. Preliminary research (unpublished) has been completed to estimate suitable habitat with limited occurrence records from the native range. Despite limited occurrences, models performed well and estimated moderate to high suitability in most temperate regions globally. These preliminary models are still being optimized by working with collaborators within the native range of JCLB to increase the number of occurrences. It is also important to note that these models are only accounting for climate data. Host data was not included, but Cupressaceae species are abundant globally, and therefore host availability is not likely a limiting factor for JCLB in establishing in regions.

Importance of monitoring species

While JCLB is still mostly limited to dead, dying trees, many of the species it may affect in the Eastern United States are already of heightened conservation concern. Wetland Cupressaceae, such as bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) and Atlantic White Cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides), are valuable in terms of ecosystem services they provide in coastal, and inland, wetlands. These wetlands are encountering heightened stress in the form of increasing saltwater intrusion, increased storm strength, and changing landscapes, all of which may predispose trees to insect attack. Japanese cedar longhorned beetle has been successfully reared out of logs of Atlantic White Cedar, but thankfully has not been documented on live trees of this species (Maier 2009)[Ma1] . Bald cypress has not yet been tested for suitability. It is unknown if the stressors these trees are facing and will continue to face will impact JCLB’s ability to infest these landscapes, or if they will remain restricted to dead trees in these coastal forests. Regardless, given JCLB already has an established foothold in the Eastern United States, it is important to better understand the potential impacts of this insect.

First steps to understanding those impacts include 1) better documenting the host range in the regions and 2) determining the climate that may support the species. Hopefully we can continue research in these areas to best manage this non-native pest.

Much of the research conducted on JCLB in North America took place almost 20 years ago (Maier 2007, 2009), so updated sampling has potential to provide a wealth of information regarding spread rate, suitable climate, and establishment patterns.

Sources

Clément F. 2023. Le point sur la distribution en France et en Europe de Callidiellum rufipenne (Motschulsky, 1861)(Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Cerambycinae, Callidiini). Le Coléoptériste. 26(3):188–203.

Maier CT. 2007. Distribution and Hosts of Callidiellum rufipenne (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), an Asian Cedar Borer Established in the Eastern United States. JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC ENTOMOLOGY. 100(4).

Maier CT. 2009. Distributional and host records of Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) associated with Cupressaceae in New England, New York, and New Jersey. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 111(2):438–453. https://doi.org/10.4289/0013-8797-111.2.438

Turienzo P. 2007. New records and emergence period of Callidiellum rufipenne (Motschulsky, 1860) [Coleoptera:Cerambycidae: Cerambycinae: Callidiini] in Argentina. Boletín de Sanidad Vegetal, Plagas. 33:341–349.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and Forest Service 2000. (Pasek, J.E., H.H. Burdsall, J.F. Cavey, A. Eglitis, R.A. Haack, D.A. Haugen, M.I. Haverty, C.S. Hodges, D.R. Kucera, J.D. Lattin, W.J. Mattson, D.J. Nowak, J.G. O’Brien, R.L. Orr, R.A. Sequeira, E.B. Smalley, B.M. Tkacz, W.W. Wallner) Pest Risk Assessment for Importation of Solid Wood Packing Materials into the United States. USDA APHIS and Forest Service. August 2000.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or

[Ma1]another old source