Numerous ambrosia beetles have become introduced species. Their invasions are facilitated by their cryptic habits and ecologies, wide host ranges, and specialized breeding systems – all of which allow extremely low populations to start an infestation. The way they breed often results in low genetic diversity in their introduced ranges, but this has not hampered their success. [Bierman et al. 2022]

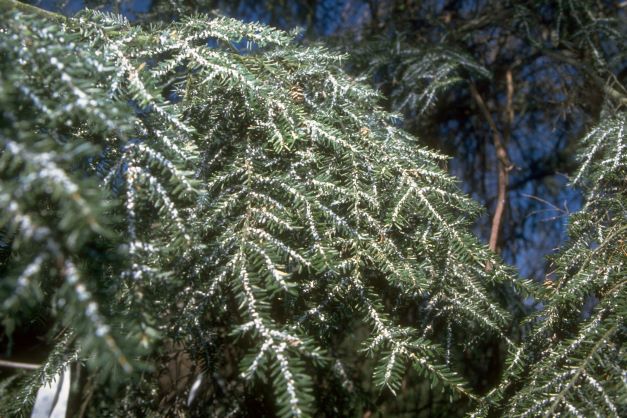

Also, ambrosia beetles carry fungi, which provide food needed by their larvae. While most of these fungi don’t harm living trees, some do. The United States has been invaded by three damaging ambrosia beetle-fungal complexes: laurel wilt in the Southeast, and Fusarium dieback disease, carried to southern California with polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers.

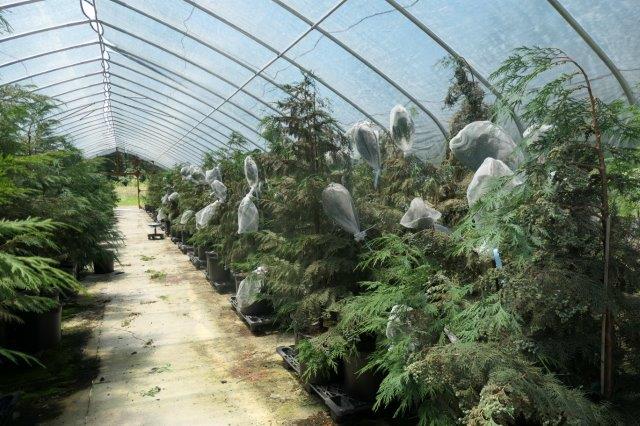

These shot hole borers and their fungi represent an especially high risk to our forests because they can be transported in both living and dead wood. So not only massive U.S. imports of live plants but also the global movement of goods enclosed in solid wood packaging offer ready pathways for them to arrive and spread here. Neither pathway is regulated effectively enough to prevent either pest imports or interstate spread.

Invasive ambrosia beetles in California and Hawai’i

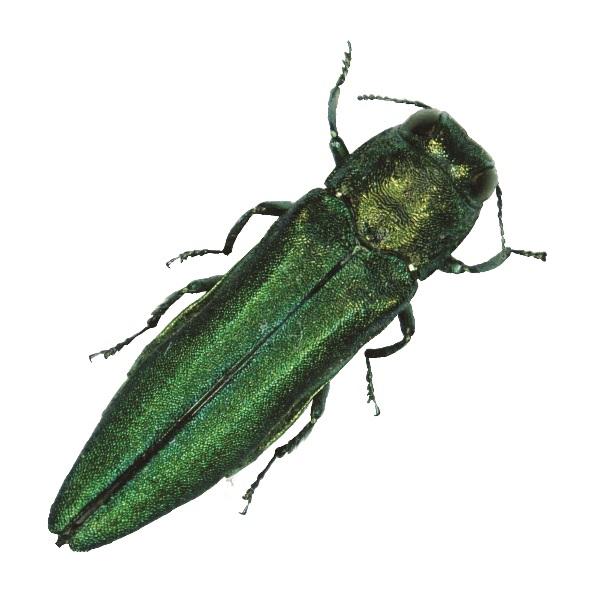

The invasive ambrosia beetles introduced to California are in the genus Euwallacea. This genus has undergone several taxonomic revisions. Now, the Euwallacea are divided into four species (Stouthammer 2017), of which three are in the U.S.:

- Euwallacea fornicatus s.s. – common name polyphagous shot hole borer; first came to attention in southern California in 2012; formerly known as E. whitfordiodendrus.

- E. perbrevis – common name tea shot hole borer; formerly known as E. fornicatus s.l.

- E. kuroshio – unchanged nomenclature since detected in California in 2013;

- E. fornicatior — apparently has not invaded outside of its native range in Asia.

Those now in the U.S. have been introduced to naïve habitats here and elsewhere, often with dire consequences. E. perbrevis, and possibly other species in the complex, are established on the Hawaiian islands.

For an extensive discussion of their introduction history go here

The Fungi: U.S. and Worldwide

Several fungal associates are vectored by the polyphagous shot hole borer (PSHB) and Kuroshio shot hole borer (KSHB). The most important are Fusarium euwallacea and Fusarium kuroshium, respectively. These fungi were only described after they appeared in California in the 2010s. They cause Fusarium dieback disease.

Because the two beetle species are difficult to distinguish and the associated diseases cause very similar impacts, Californians studying them and educating stakeholders now speak of the two beetle-fungus complexes as one unit, “invasive shot hole borers”.

Both PSHB and KSHB have numerous genetic strains, or haplotypes. For PSHB, the greatest haplotype diversity is in Asia – Thailand, Vietnam and China. Remember that these same regions are also a center of diversity for the huge genus Phytophthora, blog a genus widely recognized as containing many plant pathogens. https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/pest_pathogen/sudden-oak-death-syndrome-html/ One of the PSHB haplotypes, H33, has invaded many more regions than the others, including Israel, California, and South Africa. It has also been detected in several tropical plant greenhouses in Europe (where it has been eradicated). H33apparently is native to Vietnam – near Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City – the country’s major ports (Rugman-Jones et al 2020 and pers. comm.). Does this haplotype’s spread to three continents reflect circumstances, such as the proximity of its native range to major ports and a “bridgehead effect” from its multiple introductions (the insects can be introduced to new regions on shipments from invaded regions established earlier)? Or does it point to an unknown genetic superiority (Bierman et al. 2022). This issue seems worth exploring.

I have blogged about the rising volume of imports from Vietnam, including to ports on the Gulf Coast –a region that has climatic similarities to Vietnam and known host species, so it seems quite vulnerable to invasion by either PSHB or KSHB.

A second species in the genus, KSHB, was detected in southern California in 2012; it has now spread to Mexico. So far, only one haplotype of this species has been detected in North America; this haplotype is widespread in Taiwan.

Finally, E. perbrevis (formerly known as E. fornicatus s.l.) has been detected in Florida, Hawai`i (island of Maui), and West Australia (to which it is probably native). This species has also been detected in nurseries in the Netherlands, where authorities report that it has been eradicated (Rugman-Jones et al. 2020).

Some species or haplotypes have been detected in only one introduced location: E. fornicatus H35 and E. kuroshio (H20) in California; H38 in South Africa; H43 on Oahu and the Big Island of Hawai`i; and an unnamed haplotype in West Australia (Rugman-Jones et al. 2020).

This is a brief guide to worldwide invasions by one or more Euwallacea-fungus complexes (Rugman-Jones et al. 2020):

- Southern California — two haplotypes of E. fornicatus s.s. (H33 & H35) and E. kuroshio (one haplotype).

- Hawai`i – a unique haplotype of E. fornicatus s.s. (H43) on Oahu, the Big Island, and possibly other islands; E. perbrevis on Maui and possibly other islands.

- Israel — E. fornicatus s.s. haplotype H33 only.

- South Africa — E. fornicatus s.s. haplotype H33 and a unique haplotype (H38).

- Western Australia — a unique haplotype of E. fornicatus s.s. and E. perbrevis (which is probably native in northern Queensland).

- Greenhouses in Europe – both E. fornicatus s.s. (haplotype not specified) and – in the Netherlands — E. perbrevis; both reported eradicated.

When a location has been invaded by two or more species or haplotypes, this is probably an indication of separate introductions. Multiple introductions thus are suspected in California (Stouthamer et al. 2017; Bierman et al. 2022); South Africa (Bierman et al. 2022); and Hawai`i (Bierman et al. 2022).

As is true of other pathogens, e.g., Phytophthoras, there appears to have been a spurt of introductions in recent decades, to, e.g., California, South Africa, and the second species in Hawai`i. Bierman et al 2022 note the constantly growing number of locations with introductions.

Impact and Spread

As is common in the case of forest pests, especially pathogens, detection occurred only years after the initial introduction. In South Africa this delay was five years – from 2012 to 2017 or 2018. In California, identification of the species as PSHB in 2012 was nine years after the organism was first detected in the state (2003).

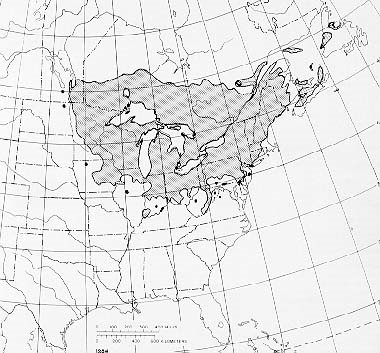

Over the decade since 2012, PHSB, KSHB, and the pathogens they transmit have spread through large portions of southern California. KSHB has spread through “jumps” to distant locations in Orange, Los Angeles, and as far as Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. There have also been detections in even more distant San Luis Obispo and Santa Clara. These latter apparently have not become established.

A likely explanation for this pattern is the movement of firewood. (Rugman-Jones et al 2020 and pers. comm.) See the map here The two beetles and the plant pathogens they carry are expected to spread throughout much of California wherever their many host plants occur.

On Hawai`i, PSHB is attacking several endemic species including one of the largest forest trees, Acacia koa, as well as Pipturus albidus and Planchonella sandwicensis. Numerous non-native species growing on the Islandsare also attacked, including crops (Macadamia and Mangifera) and invasive species

In South Africa, PSHB has spread faster and farther. It has been present since at least 2012 (Stouthamer et al. 2017), although it was not identified until 2018. In about a decade it has spread to every province except Limpopo – PSHB’s largest geographical outbreak of this beetle [Bierman et al. 2022]

Hosts and Areas at Greatest Risk

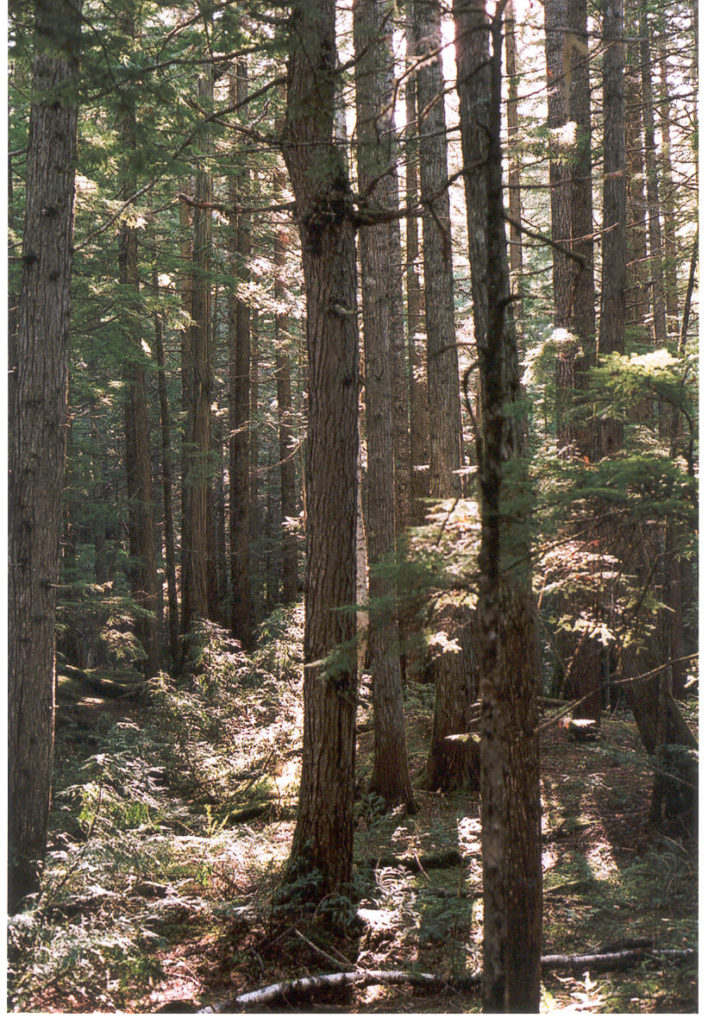

Hundreds of plant species in at least 33 plant families support successful reproduction of both beetle and fungus. These include many species widespread in southern California, other parts of the U.S., and South Africa. Some California ecosystems are at particular risk because they are dominated by susceptible tree or shrub species. These vulnerable ecosystems are mixed evergreen forests, oak woodlands, foothill woodlands, and riparian habitats. In San Diego County alone, more than 58,000 acres of riparian woodlands are at risk (California Forest Pest Council).

Experience with the Kuroshio shot hole borer (KSHB) in the Tijuana River valley along the California-Mexico border demonstrates the importance of ecological factors in determining disease outcomes. Following introduction, the KSHB killed a high proportion of the willows near the main river channel. However, beginning in 2016, these trees have regrown to almost pre-infestation sizes. Lead researcher John Boland is not certain why these new, fast-growing trees have not been attacked by the KSHB which remains in the area. See links to the Boland studies below.

Urban forests are at particular risk. For example, in South Africa, conservative estimates were that 25% of urban trees would be lost (Bierman et al. 2022). In California, a model developed by Shannon Lynch found the cities at greatest jeopardy are San Diego, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay area, and Sacramento. In other areas in the state that lack data on city tree composition, Lynch applied climate models; this approach extended the list of threatened areas to the eastern half of southern California and other parts of the Central Valley. (Lynch presentation to ISHB webinar April 2022; 2nd day.) In my view, this model should also be applied to cities in Arizona and Nevada with similar climates.

Management

Symptoms of PSHB attack and fungus infection differ among tree species. For illustrations of the symptoms on various species, visit here.

Most important, prevent the beetles’ spread through movement of dead or cut wood, e.g., green waste, firewood, and even large wood chips or mulch. Websites provide information on managing these sources.

Where the beetles have already established, California scientists recommend focusing management on heavily infested “amplifier trees”. On these trees, dead limbs should be pruned; dying trees and those with beetles infesting the main trunk should be removed. The wood must be disposed of properly.

Sources

Bierman, A., F. Roets, J.S. Terblanche. 2022. Population structure of the invasive ambrosia beetle, Euwallacea fornicatus, indicates multiple introductions into South Africa. Biol Invasions (2022) 24:2301–2312 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02801-x

Boland, J.M. — all of Boland’s reports and articles on the KSHB are available at: The Ecology and Management of the Kuroshio Shot Hole Borer in the Tijuana River Valley — Tijuana Estuary : TRNERR]

California Forest Pest Council. 2015. 2015 California Forest Pest Conditions. http://bofdata.fire.ca.gov/hot_topics_resources/2015_california_forest_pest_conditions_report.pdf

Eskalen, A., Stouthamer, R., Lynch, S. C., Twizeyimana, M., Gonzalez, A., and Thibault, T. 2013. Host range of Fusarium dieback and its ambrosia beetle (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) vector in southern California. Plant Dis. 97:938-951.

Stouthamer, R., P. Rugman-Jones, P.Q. Thu, et al. 2017. Tracing the origin of a cryptic invader: phylogeography of the Euwallacea fornicatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) species complex. Agric For Entomol 19:366-375. https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12215

recordings of April 2022 webinar posted at https://youtu.be/RyqJYyLkshk day 1; and https://youtu.be/kWmtcbjTczw day 2

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or