If you have not communicated to your Representative and senators your support for adequate funding of U.S. government programs to address non-native insects and pathogens threatening our forests, please do so now!

If political leaders do not hear from us that expanding these programs is important, these programs will continue to languish. It is easiest – and most direct – to inform your representative and Senators of your support. Please do so! If you do not agree that these programs should be expanded & strengthened, I ask that you send a comment outlining what approach you think would be more effective in curtailing introductions, minimizing impacts, and restoring affected tree species. I can then initiate a discussion to explore these suggestions. [I already have endorsed the suggestion to create a CDC-like body to oversee management of non-native forest pests.] You can find your member of Congress here. Your Senators here.

Last week the Biden Administration sent to Congress its proposed budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2021. I find it falls short in key areas. Next, the House and Senate will pass a package of appropriations bills to set actual funding levels. This is the moment to press for boosted funding. In an earlier blog I explained my reasons for seeking specific funding levels.

Two USDA agencies lead efforts to protect U.S. wildland, rural, and urban forests from non-native insects and pathogens. Their funding is set by two separate – and critical — appropriations bills:

- USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has legal responsibility for preventing introduction of tree-killing pests; detecting newly introduced pests; and initiating eradication and containment programs intended to minimize their damage. Funding for APHIS is contained in the Agriculture Appropriations bill.

- USDA Forest Service (USFS)

- The Forest Health Management (FHM) program provides funding and applied science to help partners manage pests. The program has two sides: the Cooperative component helps states and private forest managers, so it can address pests where they are first found – usually near cities – and when they spread. The federal lands component helps the USFS, National Park Service, and other federal agencies counter pests that have spread to the more rural/wildland areas that they manage.

- The Research and Development (R&D) program supports research into pest-host relationships; pathways of introduction and spread;; management strategies (including biocontrol); and host resistance breeding

Forest Service funds are appropriated through the Interior Appropriations bill.

APHIS – the Administration’s official budget proposal, and justification, is here.

The Administration proposes a small increase for three of four APHIS programs that are particularly important for preventing introductions of forest pests or eradicating or containing those that do enter. The Administration proposed significant funding for a fourth program that plays a small but important role in managing two specific forest pests.

| APHIS Program | Current (FY 2021) | FY22 Administration proposed | FY 2022 Campbell recommended |

| Tree & Wood Pest | $60.456 million | $61 million | $70 million |

| Specialty Crops | $196.553 million | 209 million | $200 million |

| Pest Detection | $27.733 million | No change | $30 million |

| Methods Development | $20.844 million | No change | $25 million |

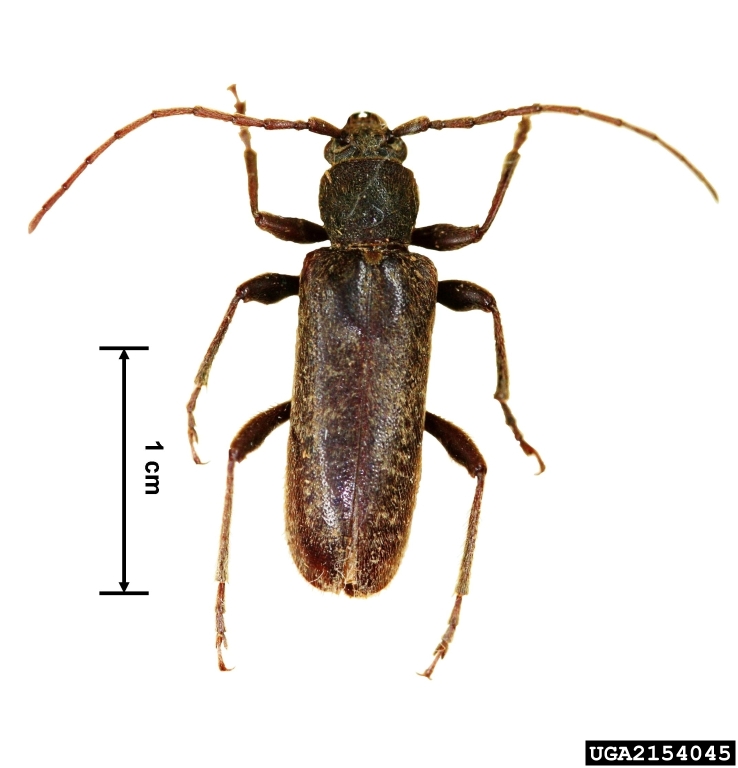

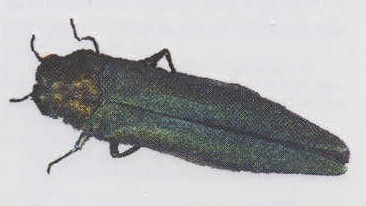

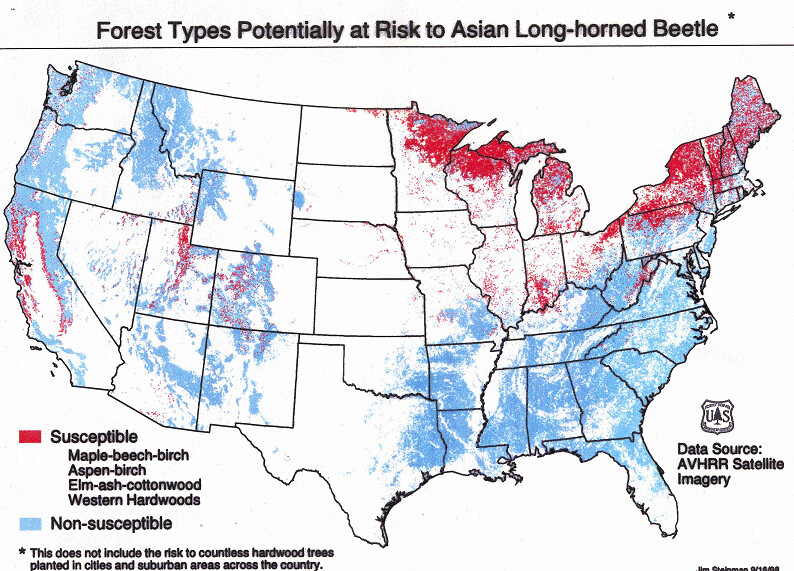

Tree and Wood Pests: It will be a major challenge for APHIS to eradicate the current outbreak of Asian longhorned beetles (ALB) in the swamps of South Carolina. APHIS should also address other pests. Even after cutting spending on the emerald ash borer (EAB), I think APHIS needs significantly more money in this account.

The Specialty Crops program is supported by such traditional USDA constituencies as the nursery and orchard industries, which probably explains the proposed increase. APHIS’ program to curtail spread of the sudden oak death (SOD) pathogen through interstate nursery trade receives funding from this program – about $5 million. I believe this program also now funds the agency’s efforts to slow spread of the spotted lanternfly.

I would like the Pest Detection program to receive a small increase so the agency and its cooperators can better deal with rising trade volumes and associated pest risk. Similarly, Methods Development should receive a boost because of the need for improved detection and management tools.

USDA Forest Service – the Administration’s official budget proposal is here.

While the Forest Health Management (FHM) and Research and Development (R&D) programs are the principal USFS programs that address introduced forest pests, neither has non-native pests as the principle focus. Non-native forest pests constitute only a portion of the programs’ activities. In the case of Research, this is a very small portion indeed.

President Biden’s budget proposes to spend $59.2 million on the Forest Health Management program and $313.5 million for Research. Both represent significant increases over spending during the current fiscal year. However, the FHM level is still below spending in recent years, although both the number of introduced pests and the geographic areas affected have been rising for decades.

In my earlier blog I suggested the funding levels:

| USFS PROGRAM | Current (FY21) | FY22 Administration | FY22 my recommendation |

| FHP Coop Lands | $30.747 million | $36.747 million | $51 million (to cover both program work & personnel costs) |

| FHP Federal lands | $15.485 million | 22.485 million | $25 million (ditto) |

| Research & Develop | $258.7 million; of which about $3.6 million allocated to invasive species | $313.560 million | $320 million; I seek report language instructing the USFS to spend more on invasive species |

Under the FHM program, a table on pp. 46-47 of the budget justification lists existing and proposed spending on 14 pest taxa (plus invasive plants and subterranean termites). Spending on these 14 species is proposed to total $30.3 million. Of this amount, less than half – $14.9 million – is allocated to such high-profile invasive species of forests as the emerald ash borer (EAB), hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), sudden oak death (SOD), and threats to whitebark pine (recently listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act). (The USFS does not engage in efforts to eradicate Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) outbreaks; it leaves that task to APHIS.) And of the nearly $15 million allocated to invasive non-native pests, more than half – $8 million – is allocated to European gypsy moths. While I agree that the gypsy moth program has been highly successful, I decry this imbalance. Other non-native pests cause much higher levels of mortality among hosts than does the gypsy moth.

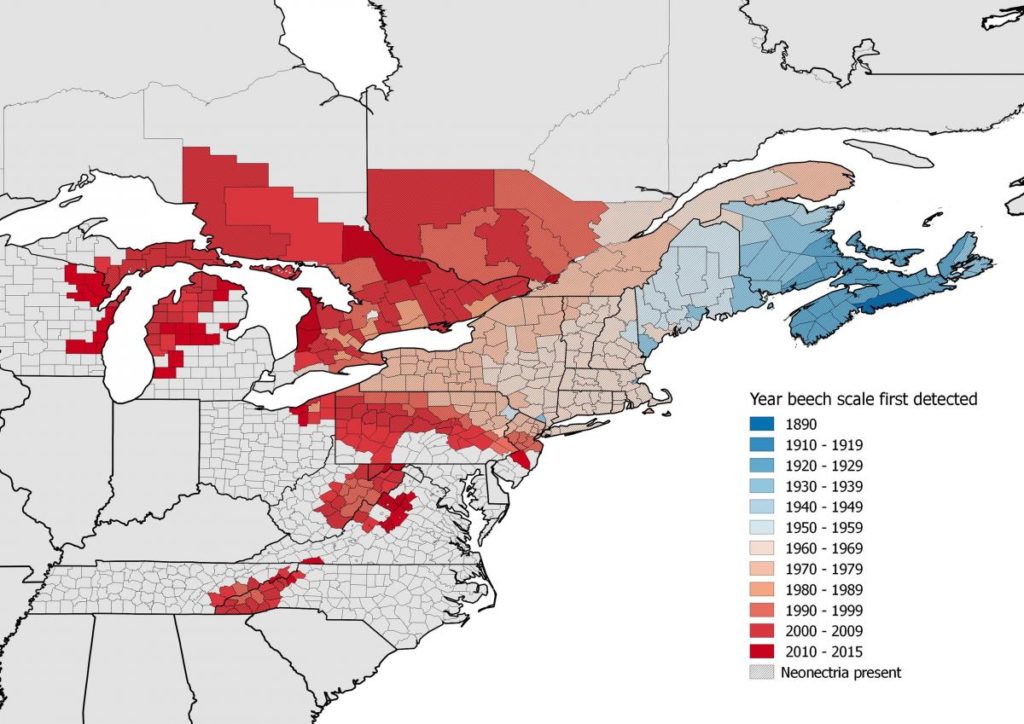

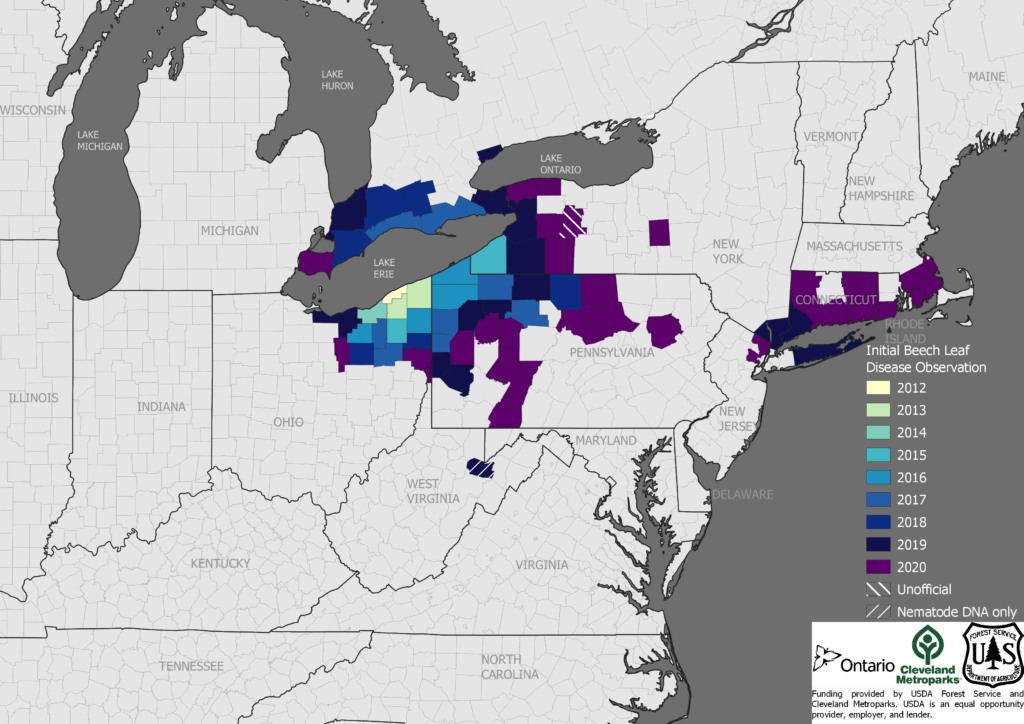

I applaud the modest increases in the Administration’s budget for other non-native forest pests. These range from tens to a few hundred thousand dollars per pest. FHM also supports smaller programs targetting rapid ohia death, beech leaf disease, the invasive shot hole borers in southern California, Mediterranean oak beetle, etc. Budget documents don’t report on these efforts.

The imbalance of funding allocated to damaging non-native pests compared to other forest management concerns is even worse in the Research program. Of the $313.5 million proposed in the budget for the full research program, only $9.2 million is allocated to the 14 pest taxa (plus invasive plants and subterranean termites) specified in the table on pp. 46-47. Of this amount, less than half — $4.5 million – is allocated to the high-profile invasive species, e.g., ALB, EAB, HWA, SOD, and threats to whitebark pine. The budget does provide extremely modest increases for several of these species, ranging from $12,000 for ALB to $114,000 for EAB. Again, some smaller programs managed at the USFS regional level might address other pests. Still – the budget proposes that USFS R&D allocate only 1.4% of its total budget to addressing these threats to America’s forests! This despite plenty of documentation – including by USFS scientists – that non-native species “have caused, and will continue to cause, enormous ecological and economic damage.” (Poland et al. 2021; full citation at the end of the blog). Poland et al. go on to say:

Invasive insects and plant pathogens (or complexes involving both) cause tree mortality, resulting in canopy gaps, stand thinning, or overstory removals that, in turn, alter microenvironments and hydrologic or biogeochemical cycling regimes. These changes can shift the overall species composition and structure of the plant community, with associated effects on terrestrial and aquatic fauna. In the short term, invasive insects and diseases can generally reduce productivity of desired species in forests. Tree mortality or defoliation can affect leaf-level transpiration rates, affecting watershed hydrology. Tree mortality … also leads to enormously high costs for tree removal, other management responses, and reduced property values in urban and residential landscapes.

I seek report language specifying that at least 5% of research funding should be devoted to research in pathways of invasive species’ introduction and spread; their impacts; and management and restoration strategies, including breeding of resistant trees. Several coalitions of which the Center for Invasive Species is a member have agreed to less specific language, not the 5% goal.

Two other USFS programs contribute to invasive species management. The Urban and Community Forest program provided $2.5 million for a competitive grant program to help communities address threats to urban forest health and resilience. Of 23 projects funded in FY2020, 11 are helping communities recover from the loss of ash trees to EAB. (On average, each program received $109,000.)

The Forest Service’ International Program is helping academic and other partners establish “sentinel gardens” in China and Europe. North American trees are planted and monitored so researchers can identify insects or pathogens that attack them. This provides advance notice of organisms that could be damaging pests if introduced to the United States.

REFERENCE:

Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States. Editors T.M. Poland, T. Patel-Weynand, D.M. Finch, C.F. Miniat, D.C. Hayes, V.M. Lopez Open access!

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm