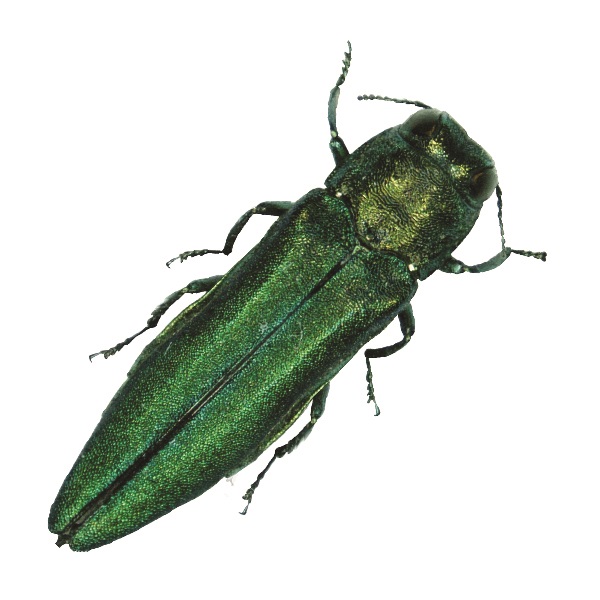

Environmental Entomology, in partnership with other journals from the Entomological Society of America, has published a special collection of papers on the spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula. All papers in the collection are freely available to read and download through February 16, 2022. I will summarize key points, with brief references to the specific article.

The papers are available at https://academic.oup.com/ee/pages/research-on-spotted-lanternfly

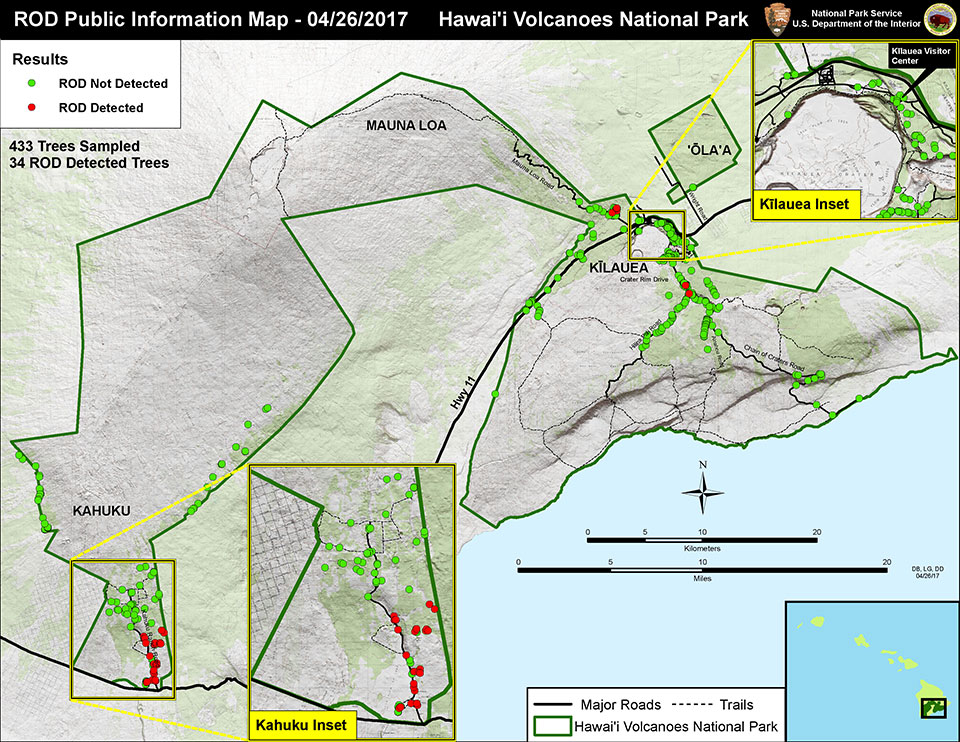

Areas at Risk

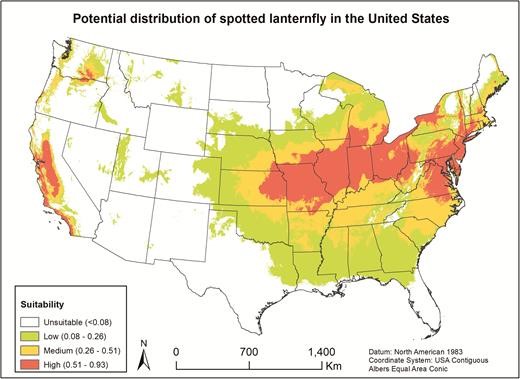

As this map shows, the spotted lanternfly (SLF) is thought able to establish in more than 26 states.

Source: T.T Wakie et al., 2020. The Establishment Risk of Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) in the United States and Globally. Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 113, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 306-314, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toz259

Host Trees

SLF prefers the invasive tree species, Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), especially for oviposition. Ailanthus is widespread, so this is not very limiting. However, the SLF can complete its life cycle in the absence of this host. [O. Uyi et al. 2020. Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) Can Complete Development and Reproduce Without Access to the Preferred Host, Ailanthus altissima. Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 1185–1190, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa083]

Spotted lanternflies have been recorded as feeding on at least 56 plant species in North America and 103 plant species worldwide; most are shrubs, trees, or stout vines. [L. Barringer and C.M. Ciafré. 2020. Worldwide Feeding Host Plants of Spotted Lanternfly, With Significant Additions From North America. Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 999–1011, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa093]

SLF aggregates on tree-of-heaven by its adult stage. However, egg masses are found on 24 types of substrates with tree-of-heaven, black cherry, black birch, and sweet cherry. [H. Liu. 2019. Oviposition Substrate Selection, Egg Mass Characteristics, Host Preference, and Life History of the Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) in North America. Environmental Entomology, Volume 48, Issue 6, December 2019, Pages 1452–1468, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvz123]

An evaluation of spotted lanternfly survivorship on 26 host plant species in 17 families found that eight species supported development from first instar to adult: black walnut, chinaberry, oriental bittersweet, tree-of-heaven, hops, sawtooth oak, butternut, and tulip tree. When offered a choice between black walnut and tree-of-heaven, nymphs showed no preference; adults showed a significant preference for tree-of-heaven. [K. Murman et al. 2020. Distribution, Survival, and Development of Spotted Lanternfly on Host Plants Found in North America. Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 6, December 2020, Pages 1270–1281, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa126]

Dispersal

Spotted lanternfly nymphs (all instars) usually moved only short distances over a 7-day period, but a few were discovered 50-65 meters away. [J.A. Keller et al. 2020. Dispersal of Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) Nymphs Through Contiguous, Deciduous Forest. Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 1012–1018, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa089]

Detection – Traps & Lures

A test of 43 host plant volatiles found 11 to be significantly attractive. [N.T. Derstine et al. 2020. Plant Volatiles Help Mediate Host Plant Selection and Attraction of the Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae): a Generalist With a Preferred Host. Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 1049–1062, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa080]

A comparison of several trap types found that circle traps caught more SLF than sticky bands, and fewer non-target organisms. Traps placed on the trunks of trees caught more SLF than traps placed in the tree canopy. [J.A. Francese, et al. 2020. Developing Traps for the Spotted Lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 2, April 2020, Pages 269–276, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvz166] In one study, addition of a lure containing methyl salicylate did not increase captures. [L.J. Nixon, et al. 2020. Development of Behaviorally Based Monitoring and Biosurveillance Tools for the Invasive Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 1117–1126, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa084] his contradicted an earlier study that suggested that traps with high release methyl salicylate lures did capture more SLF. [M.F. Cooperband, et al. 2019. Discovery of Three Kairomones in Relation to Trap and Lure Development for Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 112, Issue 2, April 2019, Pages 671–682, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toy412]

Potential Controls: Parasites, Parasitoids, and a Pathogen

Significant efforts are afoot to find possible biocontrol agents. Scientists have surveyed SLF and associated parasites/parasitoids across 27 provinces and administrative regions of China from 2015 to 2019. They recovered an egg parasitoid, Anastatus orientalis, and a nymphal parasitoid, Dryinus sinicus, and are studying these further as potential biological control agents of spotted lanternfly. [B. Xin et al. 2020. Exploratory Survey of Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) and Its Natural Enemies in China Environmental Entomology, nvaa137, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa137]

The egg parasitoid Anastatus orientalis has the advantages of being easy to rear and long lived. Research is under way to tests its host specificity. [H.J. Broadley et al. 2020. Life History and Rearing of Anastatus orientalis (Hymenoptera: Eupelmidae), an Egg Parasitoid of the Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Environmental Entomology, nvaa124, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa124]

The spotted lanternfly leaves behind a chemical trail when walking – a trail which the parasitoid wasp Anastatus orientalis uses to locate the host’s eggs. [R. Malek et al. 2019. Footprints and Ootheca of Lycorma delicatula Influence Host-Searching and -Acceptance of the Egg-Parasitoid Anastatus orientalis [Environmental Entomology, Volume 48, Issue 6, December 2019, Pages 1270–1276, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvz110]

The established gypsy moth egg parasitoid Ooencyrtus kuvanae has been observed attacking SLF egg masses in the field. [H. Liu and J. Mottern. 2017. An Old Remedy for a New Problem? Identification of Ooencyrtus kuvanae (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae), an Egg Parasitoid of Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) in North America. Journal of Insect Science, Volume 17, Issue 1, January 2017, 18, https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/iew114]

Single applications of the insect pathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana strain GHA killed 43-48% of spotted lanternflies on preferred host plants in a park. Adult spotted lanternflies feeding on potted grapevines were sprayed with the same fungus, resulting in 100% mortality after 9 days. [E.H. Clifton, et al. 2020. Applications of Beauveria bassiana (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) to Control Populations of Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae), in Semi-Natural Landscapes and on Grapevines Environmental Entomology, Volume 49, Issue 4, August 2020, Pages 854 – 864, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa064]