photo by A. Gawel

We know the dire threats to Hawaiian forests from pathogens. Some threaten the most widespread tree – ohia. Others are insects threatening trees and shrubs in the remnant dryland forests.

The forests of smaller islands of the Pacific also appear to be facing severe threats – although I have been unable to find information on the current situation.

Guam and its Neighbors

The forests of Guam, Palau, and others in the Western Pacific are among those threatened.

They are geographically isolated and hard to reach, but that distance has not protected them from biological invaders. Their predicament illustrates the dominant role of global movement and trade in spreading pests. In this case, it’s mostly trade in ornamental plants.

These islands have unique flora and fauna. And true to invasive species experts’ expectations, they are vulnerable to bioinvaders. Guam’s most famous invasive species is the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), which over a few decades eradicated many bird species and the only native terrestrial mammal, the fruit bat.

Less known, but equally damaging, have been a group of insects that are decimating Guam’s native forest flora.

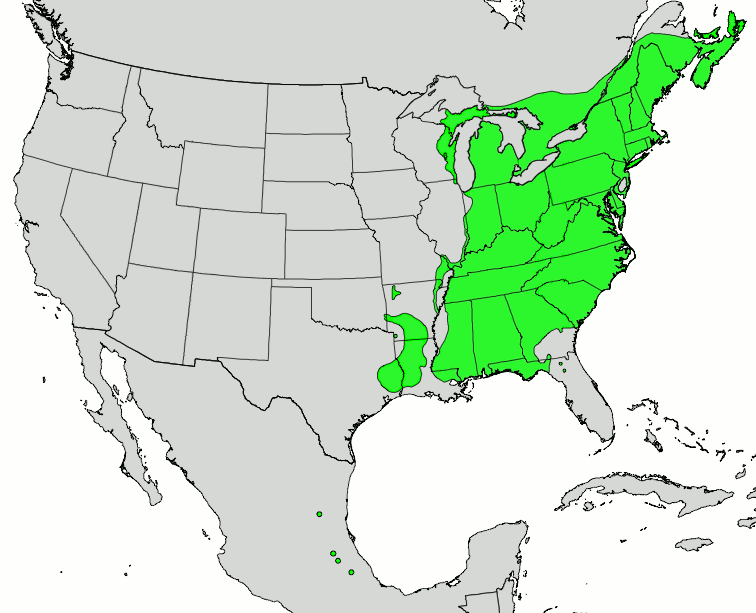

The most widespread arboreal species in the forests of Guam and neighboring islands is the Micronesian cycad, Cycas micronesica. Its range is Micronesia, the Marianas Group including Guam and Rota Islands; and several of the western Caroline Islands, e.g., Palau and Yap (Marler, Haynes, and Lindstrom 2010).

These forests have already absorbed severe habitat destruction as the sites of fierce fighting in World War II and – in some cases – construction of large military bases. Still, cycads were the most common species in the forest as late as 2002 (Moore, A., T. Marler, R. Miller, and L. Yudin. Date uncertain).

The Worst Pest: Asian Cycad Scale

The most severe current threat to the cycads are introduced insects, especially the Asian cycad scale Aulacaspis ysumatsui.

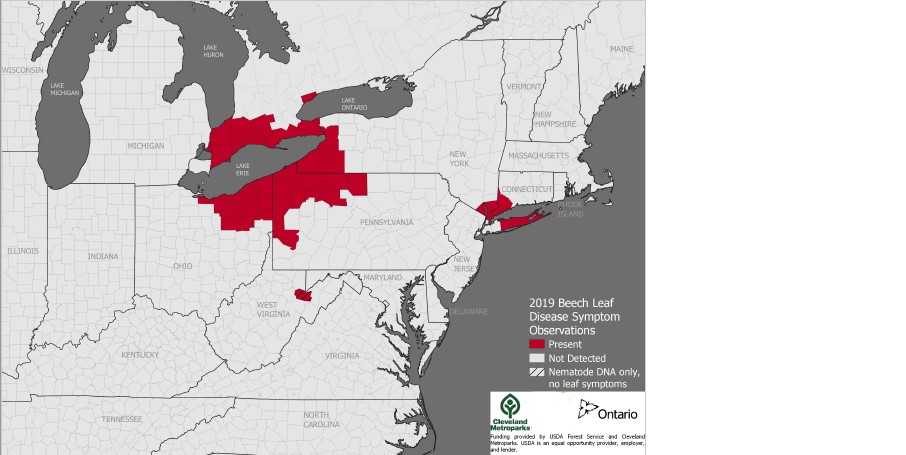

The cycad scale is native to Southeast Asia. It was first detected on Guam in 2003, when officials noticed that cycads planted near hotels had begun to die. However, this scale had already been spreading thanks to the trade in ornamental cycads. It was detected in Florida in 1996, on Hawai`i in 1998. It continued to spread rapidly in the western Pacific: to Rota in 2007, Palau in 2008 (University of Guam 2012). By late 2019, the scale had spread globally – numerous islands and neighboring mainland areas in the Caribbean (including Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands), several US states in the Southeast, California, and Taiwan (Moore, Marler, Miller, and Yudin. Date uncertain.) and South Africa. (vanWilgen, et. al. 2020) Also, see the map prepared by CABI.

In every case, the scale has apparently been spread on nursery stock. It is difficult to contain by standard phytosanitary measures – visual inspection – because the scale is tiny and hides deep in the base of the plant’s stiff leaves and other crevices. (Marler and Moore 2010)

By 2005 the scale was killing the native cycad on Guam. Within four years, the millions of C. micronesica on Guam were reduced by more than 90% (Marler, T.E. and K.J. Niklas. 2011). The last time cycads on Guam reproduced in any significant number was in 2004 (Marler and Niklas 2018).

The severe impact of the scale was so rapid that the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) changed its listing of C. micronesica from “near threatened” in 2003 to “endangered” in 2006. (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Online 2008).

Scientists have made several attempts to introduce a biocontrol agent. However, the most promising – the lady beetle Rhyzobius lophanthae – has failed to control the scale, despite having become virtually ubiquitous on Guam. The beetle is too big to reach the significant proportion of scale insects living in small cracks and voids within the plant structures. Evidence from another cycad species indicates that the beetles also don’t prey on scale insects living beneath trichomes (fine hairlike structures on the leaves) or on parts of the plant close to the ground. (Moore, Marler, Miller, and Yudin. Date uncertain.).

Attempts to introduce a second biocontrol organism – the parasitoid wasp Aphytis lignanensis – were stymied by the presence of R. lophanthae (Moore, Marler, Miller, and Yudin. Date uncertain).

photo by Lauren Gutierrez

Other Invasive Species Attacking Cycads

The cycad blue butterfly (Chilades pandava) was detected in 2005 and spread throughout Guam within months (IUCN 2009). Also, it’s been found on Saipan (1996) and Rota (2006). The butterfly is native to southern Asia from Sri Lanka to Thailand and Indonesia. High populations can cause complete defoliation of new foliage. Repeated defoliations can kill the plant. Cycads on Guam are particularly vulnerable because the scale has already caused loss of most of their leaves. Butterfly larvae are often protected by ants (Anonymous).

On cultivated plants the butterfly can be controlled by microbial insecticides containing Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Moore). Scientists at the University of Guam are exploring use of injected insecticides (Moore). They have found an egg parasite, but parasitism levels are low. Any biocontrol agent targetting larvae would have to contend with the ants (Anonymous).

A longhorned beetle (Dihammus (Acalolepta) marianarum) and a snail (Satsuma mercatorius) are also feeding on the cycads (Marler 2010).

The Indo-Malayan termite Schedorhinotermes longirostris was detected in 2011. The termites weaken the cycad stems, which are then toppled by feeding by introduced deer. The termites are also damaging the cycad’s reproductive structures (megastrobili). Termite attacks on cycads surprised scientists since cycads do not form true wood. The termite had probably been introduced recently because, as of 2011, it had been detected only near the Andersen Air Force Base airport (Marler, Yudin, and Moore 2011).

More Isolated – but Still Overrun

Scattered across the Pacific are groups of atolls, including Palmyra and Rose.

Despite their distance from other islands, they have all been visited by mariners for centuries. As a result, they have non-native species, including insects that attack trees.

The tree most affected is pisonia – Pisonia grandis.

The principal insect is another scale, Pulvinaria urbicola. There are some reports that the scale is farmed by ants; species mentioned include several introduced species such as the yellow crazy ant, Paratrechina longicornis.

The scale is probably from the West Indies. Once it reached the Pacific, it might have been distributed to additional islands on seabirds, which travel long distances between the atolls.

The scale’s impact is unclear.

At first, in the mid-2000s, impacts seemed dire. It was reported to be causing widespread tree death on Palmyra and Rose atolls, islands around northeastern Australia, in the Seychelles, and possibly in Tonga.

However, in 2018, scientists reported that eradication of rats on Palmyra Atoll had resulted in an immediate spurt of reproduction of a tree. Numbers of “native, locally rare tree” seedlings (possibly but not explicitly said to be Pisonia grandis) jumped from 140 pre-eradication to 7,756 post-eradication (in 2016). The study made no mention of the scale.

Rose Atoll has only one small island (6.6 ha) with vegetation. Before 1970, it was dominated by Pisonia grandis, but by 2012, there were only seven trees on the island. Several possible causes of this decline have been suggested. Other than the scale, suggested causes include storms, drought, rising sea level / saltwater incursion, and imbalance of bird guano-derived nutrients in the soil. [All information about Rose Atoll is from Peck et al., 2014)

A survey carried out in April 2012 and November 2013 detected 73 species of arthropods from 20 orders on Rose Island, including nine ant species (all but one non-native). Two of these ants – Tetramorium bicarinatum and T. simillimum – were detected tending the scales on Pisonia.

The survey found no evidence of natural enemies of the Pulvinaria scales.

The scientists tested treatment of Pisonia with the systemic insecticide imidacloprid. This treatment apparently reduced scale populations considerably for several months, but then they began to build up again.

In contrast to Palmyra, Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) were eliminated from Rose Atoll in 1990–1991 – so their role in destroying the trees had ended 20 years before the study. What does the continued decline of the Pisonia trees in subsequent decades suggest for the future of Pisonia trees on Palmyra?

I have sought updates on the tree-pest situations on Guam and the other Pacific islands, but my queries have not received a reply.

SOURCES

Anonymous. 2015. Cycad blue butterfly fact sheet.

Brooke, USFWS, pers. comm. June 3, 2005

CABI November 2019. Aulacaspis yasumatsui (cycad aulacaspis scale (CAS)) or the Asian cycad scale. https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/18756 (was formerly Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux (CAB) International; now apparently just uses acronym)

Marler, T.E. pers. comm. August 15, 2012

Marler, T.E. 2010. Cycad mutualist offers more than pollen transport. American Journal of Botany, 2010; 97 (5): 841. Viewed as materials provided by University of Guam, via EurekAlert; accessed 6 August, 2012.

Marler, T., Haynes, J. & Lindstrom, A. 2010. Cycas micronesica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010: e.T61316A12462113. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T61316A12462113.en Accessed 22 April, 2020.

Marler, T.E., and A. Moore. 2010. Cryptic Scale Infestations on Cycas revoluta Facilitate Scale Invasions. HortScience. 2010; 45 837-839. Retrieved August 6, 2012 from www.eurekalert.org

Marler, T.E., L.S. Yudin, A. Moore. 1 September 2011. Schedorhinotermes longirostris (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) on Guam Adds to Assault on the Endemic Cycas micronesica. https://bioone.org/journals/florida-entomologist/volume-94/issue-3/024.094.0339/Schedorhinotermes-longirostris-Isoptera–Rhinotermitidae-on-Guam-Adds-to-Assault/10.1653/024.094.0339.full

Marler, T.E. and K.J. Niklas. 2011. Reproductive Effort and Success of Cycas micronesica K.D. Hill Are Affected by Habitat. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 2011; 172 (5): 700. Viewed as materials provided by University of Guam, via EurekAlert; accessed 6 August, 2012.

Moore, A. Cycad blue butterfly fact sheet. http://www.guaminsects.net/gisac2015/index.php?title=Cycad_blue_butterfly_fact_sheet accessed 20-4/24

Moore, A., T. Marler, R. Miller, and L. Yudin. Date? Biological Control of Cycad Scale, Aulacaspis yasumatsui, Attacking Guam’s Endemic Cycad, Cycas micronesica. Western Pacific Tropical Research Center University of Guam. Powerpoint http://guaminsects.myspecies.info/sites/guaminsects.myspecies.info/files/CycadScaleBiocontrolAustin.pdf

Peck, R., P. Banko, F. Pendleton, M. Schmaedick, and K. Ernsberger. 2014. Arthropods of Rose Atoll with Special Reference to Ants and Pulvinaria urbicola scales (Hemiptera: Coccidae) on Pisonia grandis trees. Hawaii Cooperative Studies Unit. University of Hawaii. Technical Report HCSU-057 December 2014

University of Guam (2012, August 2). Invasive insects cause staggering impact on native tree. ScienceDaily. Retrieved August 6, 2012, from www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2012/08/120803094527.htm).

vanWilgen, B.W.,J. Measey, D.M. Richardson, J.R. Wilson, T.A. Zengeya. Editors. 2020. Bioinvasions in South Africa. Invading Nature. Springer Series in Invasion Ecology 14.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm These reports do not include details on the pest situation on the Pacific islands (including Hawai`i).