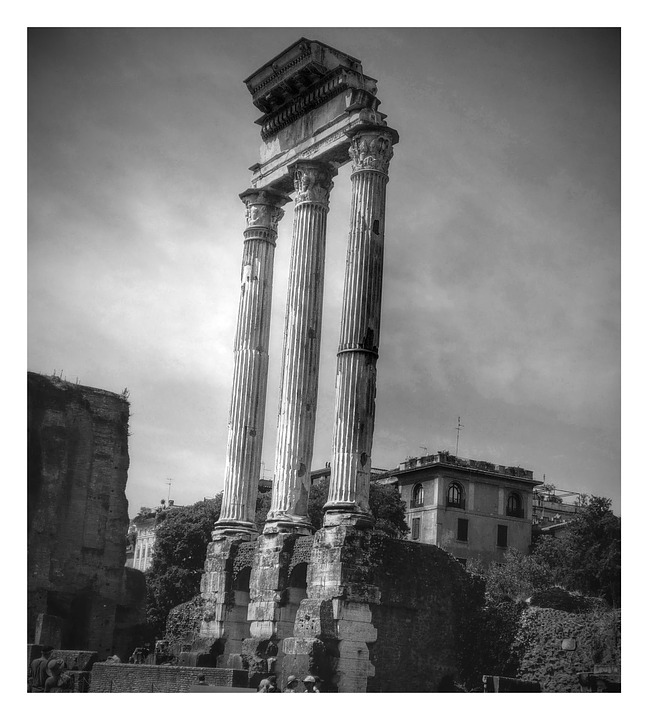

photo by Forrest and Kim Starr, courtesy of creative commons

Hawaii’s dryland forest is a highly endangered ecosystem. More than 90% of dry forests are already lost due to habitat destruction and the spread of invasive plant and animal species. However, a new publication documents some recovery of wiliwili trees from one major pest. At the same time, a new pest is spreading and killing naio, a critical dryland shrub. Both pests originated in countries that have rarely if ever been a source of U.S. pests. This is worrying because phytosanitary agencies have their hands full with imports from the usual sources. The role of California as a source of invasive species in Hawai`i has long deserved federal attention – but as far as I know has not received it.

Hope for Wiliwili Trees

The Hawaiian endemic wiliwili tree, Erythrina sandwicensis, occurs in lowland dry forests on all the major islands from sea level to 600 m. Wililwili is a dominant overstory tree in these habitats. (Unless otherwise noted, the principal source is Kaufman et al. in press – full citation at end of blog.)

The tree has been severely affected by the introduced Erythrina gall wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae (EGW). The gall wasp was detected on Oahu in 2005 and quickly spread to the other Hawaiian islands.

Arrival of the EGW on Oahu was part of the insect’s rapid global range expansion. Originally from East Africa, it was first detected in the Mascarene Islands and Singapore in 2003. At the time, it was unknown to science. Within a few years it had spread across Asia, many Pacific islands (including Hawai`i), and to the Americas, including Florida in 2006, Brazil in 2014 (Culik 2014), and Mexico in 2017 (Palacios-Torres 2017). Although apparently restricted to the Erythrina genus as host, it has lots of opportunities. This genus has 116 species distributed across tropical and subtropical regions: 72 species in the Americas, 31 in Africa, and 12 in Asia.

The severe damage to wiliwili (and to non-native Erythrina trees planted in urban areas and as windbreaks) prompted Hawaiian officials to immediately initiate efforts to find a classical biological control agent. The process moved rapidly. A candidate – a parasitic wasp species new to science, Eurytoma erythrinae – was found in East Africa in 2006. Host specificity testing was carried out. Scientists quickly learned to rear the parasitic wasp in laboratories. Release of the biocontrol agent was approved in November 2008 – only three and a half years after the EGW was detected on Oahu.

The biocontrol agent’s impact was quickly apparent. Establishment was confirmed within 1–4 months at all release locations throughout Hawai`i. Reduced pest impacts to trees were detected within two years. By 2018, only 33% of the foliage was damaged on the majority of wiliwili trees. Damage to non-native Erythrina had also declined.

Results of Biocontrol Agent’s Release

The biocontrol agent’s efficacy in reducing EGW’s impacts on trees has been evaluated for 10 years after the agent’s release. Monitoring was conducted at sites on four of the six main islands. (The monitoring program and its findings are described in Kaufman et al. in press).

I wonder how many other biocontrol agents have been monitored so closely for such a long time? Shouldn’t they all be?

Given the uniqueness and importance of such long-term assessment, it is worth looking at the data in detail.

1) Foliar Damage and Tree Health

In 2008, before release of the biocontrol agent, more than 70% of young shoots in wiliwili trees that were inspected were severely infested. The damage rating of “severe” fell from about 80% of trees in 2008 to about 40% in 2011. About 20% of trees surveyed – at sites on all islands – had no gall damage.

By three years after release of the biocontrol agent (2011), mortality rates attributed to stress from the EGW infestation for trees in natural areas fell to 21%. Mortality rates for trees in botanical gardens was somewhat higher – 34%. Kaufman et al. proposed several possible reasons: a) lingering presence of systemic insecticides that might have harmed the biocontrol agents early in the releases; b) year-round sustenance for the EGW as a result of the i) presence of alternative hosts and ii) supplemental irrigation which maintained fresh foliage on the trees.

Less intensive monitoring occurred during 2013 – 2018. It showed continuing substantial suppression of EGW damage on Erythrina foliage, although levels varied among locations. Sites with the lowest precipitation and higher temperatures throughout the year had the slowest recovery of wiliwili. Still, trees are now producing vegetative flushes and healthier canopies during non-dormant periods.

2) Flower and Seed Damage

Successful reduction of infestations in flowers and seedpods was less immediate. Still, by 2011, seed-set had increased from less than 3% of trees setting and maturing seed, to almost 30% with mature seed. The proportion of trees bearing inflorescences also increased, with more than 60% of trees blooming three years after introduction of the biocontrol agent. There was also a slow but steady increase in seed production.

However, in 2019, it remains unclear how infestation of seedpods will affect germination and therefore future plant recruitment.

More worrying, little recruitment was observed over the 10 years. Hawaiian authorities have completed tests on, and are preparing a petition for release of, a second biocontrol agent, Aprostocitus nites. It is hoped that it will further suppress EGW in flowers and seedpods.

Still, poor recruitment is likely due to the combined impacts of multiple invasive species in native environments. A significant factor is a second insect pest – a bruchid, Specularius impressithorax – which can cause loss of more than 75% of the seed crop. I hope authorities are seeking methods to reduce this insect’s impacts.

The Hawaiian species group of the IUCN has given the wiliwili tree the Reed Book designation of “vulnerable”.

Worries for Naio

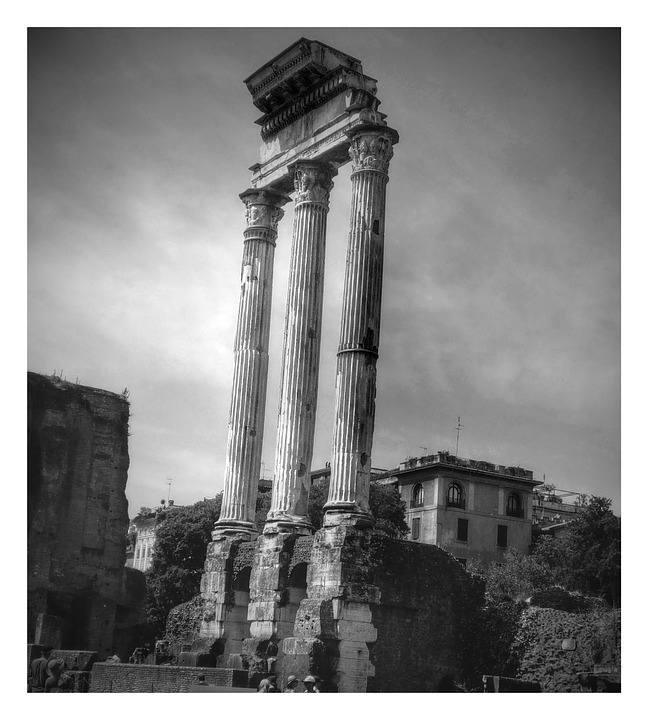

photo by Forrest and Kim Starr, courtesy of creative commons

Naio (Myoporum sandwicense)is an integral component of native Hawaiian ecosystems, especially in dry forests, lowlands, and upland shrublands. However, it is also found in mesic and wet forest habitats. Naio is found on all of the main Hawaiian Islands at elevations ranging from sea level to 3000 m. The loss of this species would be not only a significant loss of native biological diversity but also a structural loss to native forest habitats.

The invasive non-native Myoporum thrips, Klambothrips myopori, was detected on the Big Island (Hawai‘i Island) in 2009 – four years after it was first detected on ornamental Myoporum species in California. At the time of the California detection, the species was unknown to science. It is now known that this species is native to Tasmania.

The thrips feeds on and causes galls on plants’ terminal growth and can eventually lead to death of the plant.

For close to a decade, the Myoporum thrips was restricted to the Big Island. It has now been found on Oahu (Wright pers. comm.) Alarmed by the high mortality of plants in California, in September 2010, the Hawaii Department of Lands and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife and the University of Hawai‘i initiated efforts to determine spatial distribution, infestation rates, and overall tree health of naio populations on the Big Island. Monitoring took place at nine protected natural habitats for four years. This monitoring program was supported by the USFS Forest Health Protection program. (See also the chapter on naio by Kaufman et al. 2019 in Potter et al. 2019 – full citation at the end of this blog.)

photo by Leyla Kaufman, University of Hawaii

The monitoring confirmed that the myoporum thrips has spread and colonized natural habitats on the leeward side of Hawai`i Island. Infestation rates increased considerably at all sites over the duration of the four-year sampling period. Trees experiencing high infestation levels also showed branch dieback.

Medium-elevation sites (between 500–999 m) had the highest infestations and dieback: over 70% of the shoots had the worst damage.. At two sites, over 70% of the monitored trees have died.

Even though flowers and fruits were still seen at all sites, little to no plant recruitment was observed at these sites. Thus another plant species important in this endangered plant community is in decline.

Few management strategies are available for this pest. They include preventing spread to other islands and early detection followed by rapid application of pesticides.

Implications and Conclusions

The Erythrina gall wasp and myoporum thrips are only two of the thousands of invasive species established in Hawai`i. Island ecosystems, especially Hawai`i, are well recognized as especially vulnerable to invasive species. It has been estimated that on average 20 new arthropod species become established in Hawai`i every year.

East Africa and Tasmania are new sources for invasive species. Phytosanitary agencies need to adjust their targetting of high-risk imports to recognize this reality. Regarding the Hawaiian introduction of the thrips, there was probably made an intermediary stop in California – which is not unusual. (See also ohia rust.)

I applaud Hawaiian officials’ quick action to counter these pests. I wish their counterparts in other states did the same.

There are multiple threats to Hawaii’s dry forests, including habitat modification and fragmentation; wild fires; seed predation by rodents; predation on seeds, seedling, and saplings by introduced ungulates (e.g. feral goats, pigs and deer); competition with invasive weeds; and damage by invasive insect pests and diseases.

With so much of Hawaii’s dry forests already lost, the release of biocontrol agents targetting specific pests is only one element of a much-needed effort. Long-term protection of wiliwili and naio depends on greater efforts to reduce all threats and to stimulate natural regeneration of this ecosystem. These programs could include predator-proof fencing to keep out ungulates; baiting rodents and snails; and active collection. Breeding, and planting of threatened plant species in an effort to protect both the individual species and the habitat.

SOURCES

Culik, M.P., D. dos Santos Martins, J. Aires Ventura & V. Antonio Costa. The invasive gall wasp Quadrastichus erythrinae (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) in South America: is classical biological control needed?

Kaufman, L.V., J. Yalemar, M.G. Wright. In press. Classical biological control of the erythrina gall wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae, in Hawaii.: Conserving an endangered habitat. Biological Control. Vol. 142, March 2020

Palacios-Torres, R.E., J. Malpica-Pita, A.G. Bustamante-Ortiz, J. Valdez-Carrasco, A. Santos-Chávez, R. Vega-Muñoz and H. Vibrans-Lindemann. 2017. The Invasive Gall Wasp Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim in Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist.

Potter, K.M. B.L. Conkling. 2019. Forest Health Monitoring: National Status, Trends, and Analysis 2018. Forest Service Research & Development Southern Research Station General Technical Report SRS-239

Kaufman, L.V, E. Parsons, D. Zarders, C. King, and R. Hauff. 2019. CHAPTER 9. Monitoring Myoporum thrips, Klambothrips myopori (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae), in Hawaii

Wright, Mark. 2005. Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist, University of Hawaii. Personal communication.