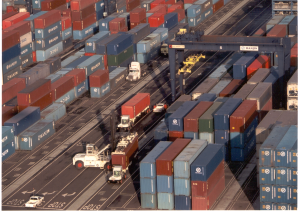

shipping container being unloaded at Long Beach

shipping container being unloaded at Long Beach

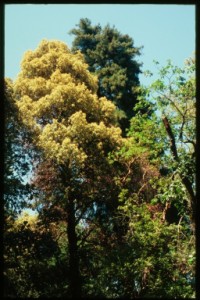

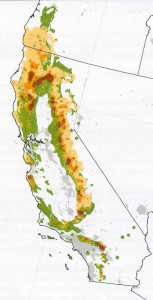

The rising numbers of tree-killing wood-boring insects introduced to the U.S. (see blogs from July 15 and August 3 & fact sheet and sources linked there) are a result of ballooning of trade volumes and use of wood packaging.

This irruption of trade was made possible by adoption of the shipping container to transport a wide range of goods.Moving from place to place are not just finished products but also components that originated in one country and that are to be assembled in another country.

How the shipping container revolutionized trade and manufacturing is detailed by Marc Levinson in his book, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton University Press 2008). The transformation affected not only trade between countries, but also within countries, with some regional economies growing while others faltered.

Dr. Levinson recognizes that he has not addressed environmental damage caused by massive movement of cargo. While Dr. Levinson does not explain which damage he is thinking about, I doubt that he includes introductions of non-native wood-boring pests.

(I don’t know enough about the ballast water pathway to understand the impact of containerized shipping on introductions of aquatic invaders, but it seems likely to be an important factor through three factors: directing trade to new port areas; the ships’ huge size; and taking on of ballast water for those segments of a voyage carrying fewer filled cargo containers. On the other hand, Dr. Levinson says that a balance of cargo moving both ways on a trade route is an important factor in determining which ports thrive.)

Before containers, port costs represented the highest proportion of transport costs. Those costs are no longer an important consideration in determining manufacturing and transport choices. Nor is distance as important as before. What is most important are ports that can move large volumes of goods efficiently. The manufacturer or retailer at the top of the chain finds the most economical place for each step in the manufacturing and assembly process without regard to its location.

The containerization revolution was rapid. Containers were first used in international trade in 1966; within three years, nearly one-third of Japanese exports to the U.S. were containerized, half of those to Australia. In the decade after containers were first used in international trade, the volume of international trade in manufactured goods grew more than twice as fast as the volume of global manufacturing production, 2.5 times as fast as global economic output. Large numbers of specialized container ships were built, at ever-increasing sizes. The largest container ship in 1969 could carry 1,210 20-ft containers. By the early 2000s, ships being built to carry 10,000 20-foot containers; or 5,000 40-foot containers.

When Dr. Levinson wrote his book in 2005, the equivalent of 300 million 20-foot containers were crossing the world’s oceans each year.

The container revolution interacted with “just-in-time” manufacturing, which required rapid and reliable transport. Large companies signed written contracts with suppliers and shippers which included penalties for delays.

In the U.S., Long Beach quickly became the principal port because it (as well as Oakland and Seattle) had excellent rail connections to the interior. By 1987, one-third of containers from Asia destined for the East Coast landed at Long Beach and crossed the U.S. by rail. Perhaps counter to our expectation, only one-third of containers entering southern California in 1998 contained consumer goods. Most of the rest contained intermediate or partially processed goods as part of the new international supply and manufacturing chain.

On the East coast, Charleston SC and Savannah similarly grew because of transport connections – this time, primarily highways.

So, global trade is huge and growing; and the shipping container moves immense quantities of goods from one ecosystem to another and provide shelter for a vast range of hitchhiking living organisms (in addition to insects in the wood, there can be other insects’ eggs attached to the sides of the container, snails, weed seeds, even vertebrates – a raccoon once staggered out of a shipping container that had crossed the Atlantic from the U.S. to France!).

We need to imagine, test, and apply a variety of tools to suppress the numbers of living organisms traveling in shipping containers.

For example,

• if importer-supplier contracts specify penalties for delivery delays, we should ask why don’t importers amend the contracts to add penalties for non-compliant wood packaging?

• Might the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection incorporate the wood packaging requirements into its “Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism” (C-TPAT) program.

• A decade ago, USDA APHIS funded research which developed an ingenious method for detecting mobile pests inside a container. It was an LED light attached to a sticky trap. Placed inside a container, the light attracted snails, insects and possibly other living organisms. The whole mechanism was attached to a mailing container that could be pre-addressed for sending to a lab that could identify the pests. Why was this tool never implemented?

We can’t stop the trade, but we can be much more aggressive in adopting measures to minimize pest introductions.

Posted by Faith Campbell