USDA headquarters; F.T. Campbell

USDA headquarters; F.T. Campbell

To my complete surprise, USDA APHIS has finalized a four-year-old proposal to temporarily prohibit importation of 56 taxa of plants: 22 that are likely to be invasive and 34 that are hosts of eight insects, pathogens, or other types of plant pests.

On June 19, APHIS published a notice in the Federal Register announcing that APHIS had finally acted on a proposal initially published on May 6, 2013. To view the datasheets APHIS prepared and the comments APHIS received, go here.

Under APHIS’ regulations in ‘‘Subpart— P4P’’ (7 CFR 319.37 through 319.37–14 …), APHIS prohibits or restricts the importation of “plants for planting” – living plants, plant parts, seeds, and plant cuttings – to prevent the introduction of “quarantine pests” into the US. A “quarantine pest” is defined in § 319.37–1 as a plant pest or noxious weed that is of potential economic importance to the United States and not yet present in the country, or is present but is not widely distributed and is being officially controlled.

Section 319.37–2a authorizes APHIS to identify those plant taxa whose importation is not authorized pending pest risk analysis (NAPPRA) in order to prevent their introduction into the United States. As regards plant taxa that have been determined to be probable invasive species, such importation is restricted from all countries and regions. For taxa that have been determined to be hosts of a plant pest, the list includes (1) names of the taxa, (2) the foreign places from which the taxa’s importation is not authorized, and (3) the quarantine pests of concern.

The plant taxa now regulated because they host various types of plant pests are listed in two parts.

1) Species designated during the first round of action were proposed in 2011 and finalized in 2013 =

2) Species proposed in 2013 and finally designated on June 19, 2017 =

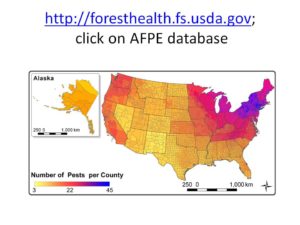

In summary, the second round of NAPPRA seeks to prevent introduction of the following specific pests by prohibiting imports of their associated plants from most countries. Imports from Canada are often excepted and those from the Netherlands less often.

- Asian longhorned beetle (ALB, Anoplophora glabripennis) – Celtis, Cercidiphyllum (katsura), Koelreuteria, Tilia

- Great spruce bark beetle (Dendroctonus micans) – Pseudotsuga

- Japanese pine sawyer (Monochamus alternatus) – Cedrus

- Phytophthora kernoviae – 17 genera, including Camellia, Fagus, Hedera, Ilex, Leucothoe, Liriodendron, Magnolia, Pieris, Quercus, Rhododendron, Sequoia, Vaccinium

- Boxwood blight (Puccinia buxi) – Buxus (boxwood)

There are other restrictions on plant imports related to pests, which predate the most recent NAPPRA listing. These include =

- Acer is already listed on the previous NAPPRA list for all countries except Canada, Netherlands, and New Zealand.

- Longstanding regulations prohibit the importation of Abies species from all countries except Canada. The genera Larix, Picea, and Pinus were added to the NAPPRA list in the April 2013 NAPPRA notice.

- Camellia was also listed in 2013 from all countries, except Canada, to prevent introduction of the citrus longhorned beetle (CLB, Anoplophora chinensis); the genus is also regulated for Phytophthora ramorum. The most recent action now adds restrictions because Camellia is also a host of Phytopththora kernoviae. Plants from Canada are exempt because of longstanding “significant trade” volumes.

- While plants in the genus Cercidiphyllum (katsura) may be imported from the Netherlands – despite the presence in the country of both ALB and CLB – a 2013 Federal Order (DA–2013–18) specifies mitigation actions which exporting countries must take to prevent transport of these insects via trade in this or other genera.

- Hedera was added to the NAPPRA list via the first round of proposals in April 2013 as a host of CLB. Under the 2013 proposal, the genus is also listed as host of Phytophthora kernoviae.

- Vaccinium are consistently exported only from Canada and Australia. The genus is listed because it is a host of Phytophthora kernoviae.

As APHIS notes in its explanation in the Federal Register, P. kernoviae has been reported in England, Ireland, and New Zealand; APHIS considers this to be evidence of spread of the pathogen through the global movement of plants. APHIS notes further that the pathogen has a large number of confirmed hosts and there is currently no effective control measure. APHIS does not note that the native range of P. kernoviae is unknown.

APHIS received considerable pushback on its proposal to restrict importation of Callistephus, Chrysanthemum, and Eustoma spp. to prevent introduction of several pathogens, including chrysanthemum stem necrosis virus (CSNV) and chrysanthemum white rust. In response, APHIS has withdrawn these three genera from the new NAPPRA listing while it conducts a commodity import evaluation document (CIED) for Chrysanthemum.

I have not discussed here NAPPRA as it applies to invasive plants. In April I blogged about the need for APHIS to act. Plants listed because of their invasive potential are posted here =

1) 2013 listing: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/plant_imports/Q37/nappra/downloads/QuarantinePestPlants.pdf

2) 2017 listing: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/plant_imports/Q37/nappra/downloads/quarantine-pest-plants-round2.pdf

Again, I welcome USDA’s finalization of this second round of regulations and look forward to new proposals.

History of NAPPRA

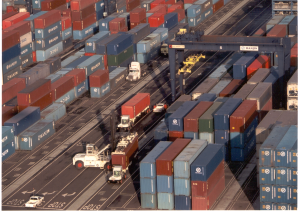

In December 2004 APHIS published in the Federal Register an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, or ANPR which outlined a strategy for reducing pest introductions via the “plants for planting” pathway. The strategy had two major steps.

First, the agency would create a temporary holding category for plants suspected of transporting insects or diseases. This would allow APHIS to suspend imports of particular plants, from certain countries, until a full risk assessment was completed.

Second, APHIS would issue regulations establishing a general framework to minimize the presence of pests. Using this, the agency would negotiate country-specific requirements for imported plants, working toward an approach that would rely on “integrated measures” (also called “integrated pest management”).

APHIS formally proposed to create the temporary holding category – the NAPPRA program – in 2009. The regulations were finalized in May 2011 – six and one half years after the intention to take this action was announced in the ANPR. In adopting the NAPPRA rule, APHIS reiterated the need to encourage, but not require, the plant import trade either to rely on low-risk plant materials or to adopt pest-reduction methods.

In July 2011, APHIS published the initial list of species proposed for inclusion in the NAPPRA category. This list was finalized in April 2013. A second list of species proposed for NAPPRA listing was published in May 2013.

This history – with citations – can be found in chapter 4, “Invasion Pathways”, in my report Fading Forests III, available here.

Meanwhile, here are a few related FAQs about NAPPRA as it is being implemented.

Why does APHIS regulate by genus?

APHIS regulates pests’ hosts at the genus level because when a new species is identified as a host, additional scientific studies often identify other host species within that genus. Therefore, regulating all species within the genus is the preferred course of action until a formal Pest Risk Analysis (PRA) is conducted. Uncertainties are worked out then.

How do these new rules fit into international standards?

APHIS notes in the Federal Register notice that the “plants for planting” pathway is recognized as posing a high risk for the introduction of pests. For this reason, the International Plant Protection Convention recommends that countries require a pest risk analysis before allowing importation of a plant taxon from a new country or region.

How long is importation of plants prohibited?

NAPPRA listing does not prohibit the importation of taxa indefinitely. Imports are held up until a pest risk analysis can be conducted to identify appropriate mitigation measures. Furthermore, an importer may apply for a controlled import permit to import small quantities of a prohibited or restricted taxon for developmental purposes.

What is the meaning of “significant trade”?

If a taxon that is a host of a quarantine pest has been imported in ‘‘significant’’ quantities from a specific exporting country, it is not eligible for the NAPPRA prohibition. Currently APHIS defines “significant trade” as the importation of 10 or more plants of a taxon in each of the previous three fiscal years. At the urging of one commenter, APHIS is considering whether to alter that definition by looking at import volumes over three out of five years – although the agency said if it took that action, it would most likely also consider raising the base number of plants from 10 to a higher level.

In the case of “significant trade” in a taxon that is a host of a quarantine pest, APHIS specifies other measures to address the pest risk.

What other protections does APHIS use?

A “Federal order” is used to rapidly take action to prevent the introduction of a quarantine pest, and is generally followed by notice and an opportunity for public comment. This is a separate action from the NAPPRA process.

OTHER PENDING USDA RULES

The Overhaul of Regulations for “Plants for Planting (P4P) (the “Quarantine-37” or “Q-37” regulations) – Will It Also Be Finalized?

Another important APHIS action aimed at improving control over introductions of pests on imported plants has also been unresolved for four years. This is the revision to the agency’s overall plant import regulations, which was also proposed in May 2013. The revision would restructure the current regulations by moving specific restrictions on the importation of taxa from regulations to the Plants for Planting Manual. That transfer would allow specific restrictions to be changed without going through the full public notice and comment process required for amending formal federal regulations. The proposed revision would also add a framework for requiring foreign plant suppliers to implement integrated pest management measures to reduce pest risk. Experts believe that depending on integrated measures will better prevent pest introductions than the current reliance on a visual inspection at the time plants are shipped.

Again, for a history of and rationale for the proposed regulatory change, read chapter 4, “Invasion Pathways”, in my report Fading Forests III, available here.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org