i`iwi; photo by James Petruzzi; courtesy of American Bird Conservancy

As noted in an earlier blog (“When Will Invasive Species Get the Respect They Deserve?” May 2016), invasive species can cause extinctions – especially on islands. I have posted other blogs about the invasional meltdown in Hawai`i (“Hawaii’s unique forests now threatened by insects and pathogens” October 2015).

A further demonstration of the meltdown is the decision by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to propose listing another Hawaiian honeycreeper (bird) – the i`iwi (Drepanis (Vestiaria) coccinea) as a threatened species. Already, some 20 Hawaiian forest birds are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Many, although not all, are threatened by the same factors as the i`iwi.

The proposal, which summarizes an extensive supporting report, is available here. USFWS is accepting comments on the proposal that are submitted to the USFWS’ website before November 21.

The proposal documents the tragedy of Hawai`i. The i`iwi was once almost ubiquitous on the islands, from sea level to the tree line. Today the bird is missing from Lanai; and reduced to a few individuals on Oahu, Molokai, and west Maui. Remaining populations of i`iwi are largely restricted to forests above ~ 3,937 ft (1,200 m) on Hawaii Island (Big Island), east Maui, and Kauai.

In the past, hunting for the bird’s striking red feathers and agricultural conversion doubtless affected the i`iwi’s populations. Since the early 20th Century, though, the threats have all been invasive species.

The USFWS has concluded that the principal threat is disease: introduced avian malaria — caused by the protozoan Plasmodium relictum and vectored by introduced mosquitoes (Culex quinquefasciatus). A second disease, Avian pox (Avipoxvirus sp.), is also present but scientists have not been able to separate its effects from those of malaria. Both vectored by the southern house mosquito.

I`iwi are very susceptible to avian malaria; in lab tests, 95% of birds died.

I’iwi on `ohi`a blossom at Hakalau NWR; photo by Daniel J. Lebbin; courtesy of American Bird Conservancy

I`iwi alive now have survived because they live in forests at sufficiently high elevations; there, cooler temperatures reduce the numbers of mosquitoes, and thus transmission of the disease. However, the birds must fly to lower elevations in certain seasons to find flowering plants (the i`iwi feeds on nectar) – and then becomes exposed to mosquitoes.

Worse, climate change has already caused warming at higher elevations, and is projected to have a greater impact in the future. The rising temperatures predicted to occur – even if countries meet their commitments from the December 2015 meeting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – will result in upslope movement of mosquitoes. As a result, according to three studies reviewed by the USFWS, the i`iwi will lose 60 – 90% of its current (already limited) disease-free range by the end of this century, with significant effects occurring by 2050.

I`iwi occur primarily in closed canopy, montane wet or montane mesic forests composed of tall-stature `ohi`a (Metrosideros polymorpha) trees or in mixed forests of `ohi`a and koa (Acacia koa) trees. The i`iwi’s diet consists primarily of nectar from the flowers of `ohi`a and several other plants, with occasional insects and spiders.

Hakalau National Wildlife Refuge; USFWS photo

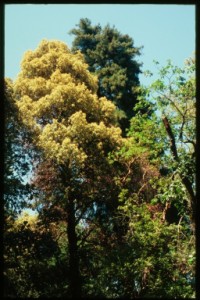

The i`iwi’s dependence on `ohi`a creates another peril, because `ohi`a trees are vulnerable to alien diseases – both ohia rust and, especially, rapid ohia death or Ceratocystis ohia wilt. (Read descriptions of both diseases here. As of September 2016, rapid ohia death has been found only on Hawai`i – the “Big Island”. However, 90% of all i`iwi currently reside on the Big Island! Worse, in future the relatively large area of high-elevation `ohi`a dominated forest on the Big Island was expected to be the principal refuge of the i`iwi from the anticipated climate-driven up-slope movement of malaria. However, as just noted, the Big Island’s trees are now being killed by disease. If rapid ohia death continues to spread across the native `ohi`a forests – on Hawai`i and potentially on the other islands – it will directly threaten i`iwi by eliminating the limited, malaria-free native forest areas that remain for the species.

Rapid `ohi`a death (ROD) is caused by two distinct strains of the widely introduced pathogen Ceratocystis fimbriata. It was first detected in the Puna District of Hawai`i in 2012. The disease has since been detected across a widening area of the Big Island, including on the dry side of island in Kona District (See map here. The total area infested has increased rapidly, from ~6,000 acres in 2012 to 38,000 acres in June 2016. Since symptoms do not emerge for more than a year after infection, the infested area is probably larger. ROD kills `ohi`a in all size and age classes. There is no apparent limit based on soil types, climate, or elevation. O`hi`a growing throughout the islands appears to be vulnerable, from cracks in new volcanic areas to weathered soils; in dry as well as mesic and wet climates. The pathogen is probably spread by spores sticking to wood-boring insects and – over short distances – wind transport of insect frass.

Federal and state agencies are spending $850,000 on research on the disease, possible vectors, and potential containment measures. Additional funds would be needed to implement any strategies, and to expand outreach to try to limit human movement of infected plants or soil.

The Hawaii Department of Agriculture adopted an interim rule in August, 2015 which restricts the movement of `ohi`a plants, plant parts, wood, and frass and sawdust from Hawai`i Island to neighboring islands. Soil was included in the interim rule with an effective date of January 1, 2016. In March 2016, HDOA approved permit conditions for movement of soil to other islands. The interim rule is expected to be made permanent at a meeting of the Board of Agriculture on 18 October.

Other invasive species threatening the i`iwi are feral ungulates, including pigs (Sus scrofa), goats (Capra hircus), and axis deer (Axis axis). All degrade `ohi`a forest habitat by spreading nonnative plant seeds and grazing on and trampling native vegetation. Their impact is exacerbated by the large number of invasive nonnative plants, which prevent or retard regeneration of `ohi`a forest. Drought combined with invasion by nonnative grasses have promoted increased fire frequency and the conversion of mesic `ohi`a woodland to exotic grassland in many areas of Hawaii.

The feral pigs pose a particular threat because by wallowing and overturning tree ferns (Cibotium spp.) they create pools of standing water in which the mosquitoes breed. The US FWS has concluded that management of feral pigs – across large landscapes – might be a strategic component of programs aimed at managing avian malaria and pox.

One possible source of hope: research into genetic manipulation of the mosquito disease vector by using tools from synthetic biology and genomics (see draft species status report . Considerable research is probably necessary before such a tool might be implemented.

Plant Pest Threat to Endangered Animals is Not Limited to Hawai`i

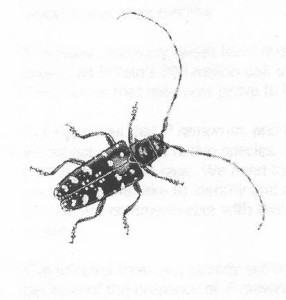

The USFWS is struggling to deal with the threat posed by plant pests to listed species. In San Diego, California, FWS personnel are trying to decide how to address the threat posed by the Kuroshio shot hole borer (read description here to willows which constitute essential riparian habitat for the least Bell’s vireo.

Numerous cactus species that have been listed as endangered or threatened might be attacked by two insects from Argentina, the cactus moth and Harissia cactus mealybug (see my blog from October 2015; or read descriptions here .

Endangered Species Agencies Need to Coordinate with Phytosanitary Agencies

A growing number of species listed under the Endangered Species Act are being threatened by damage to plants from non-native plant insects and pathogens. This growing damage affects not just listed plants – such as the cacti mentioned in this and the October blogs; but also plants that are vitally important habitat components on which listed animals depend. The USFWS needs to engage with other federal and state agencies and academic institutions which are working to prevent introduction of additional plant pests, slow the spread of those already in the United States, and develop and implement strategies intended to restore plant species that have been seriously depleted by such pests. The USFWS should, therefore, work more closely with USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and Forest Service. USFWS must, of course, continue to work with experts in wildlife and wildlife disease.

Similarly, state wildlife agencies also need to coordinate their efforts with their counterparts in state departments of Agriculture and divisions of Forestry.

Many agencies in Hawai`i play crucial roles in protecting the Islands’ unique plant and animal communities:

- U.S. Department of the Interior: Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, United States Geological Service Biological Resources Division

- US. Department of Agriculture: APHIS, Forest Service, Agriculture Research Service, National Institute of Food and Agriculture

- US. Department of Homeland Security Bureau of Customs and Border Protection.

- Hawai`i State Department of Agriculture and Department of Land and Natural Resources

Hawaiians of all types – federal and state employees and agencies, academics, and conservationists – deserve our thanks for promptly taking action of rapid ohia death. All parties should make every effort to obtain the remainder of the funds needed to carry forward crucial research on ROD and avian malaria. Those of us from the mainland need to support and help their efforts.

Posted by Faith Campbell