Amynthes agrestis; National Park Service photo

Amynthes agrestis; National Park Service photo

Earthworms have been largely ignored as a class of invaders. But evidence is accumulating that their numbers and impacts are too significant to ignore.

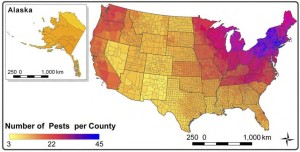

Non-indigenous earthworms began arriving in the Americas with the first European colonists and they are now widespread. One study (see summary of Reynolds and Wetzel 2008 here) found 67 introduced species among the 253 earthworm species in North America (including Mexico, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Bermuda). In Illinois, 20 of the 38 species are introduced. Nuzzo et al. 2009 recorded a total of 11 earthworm species – all nonnative – at 15 forest sites in central New York and northeastern Pennsylvania.

Earthworms are good invaders – they reproduce quickly and are easily transported to new places – both carelessly and deliberately for bait, composting, or other uses.

As ecosystem engineers, invasive earthworms cause significant impacts to the soil and leaf litter, as well as to plants and animals dependent on those strata. However, they are little studied and few efforts been made to address their threat. Wisconsin is the pioneer (see below).

Ecosystem Engineers: Impacts on Soil, Plants, and Animals

Invasive alien earthworms cause enormous damage in forest environments. (I have seen no information about the damage they might cause in other natural systems.) Earthworms can change soil chemistry, soil structure, and the quantity and quality of the litter layer on the soil surface. Changes include rapid incorporation of leaf litter into the soil, alteration of soil chemistry, changes in soil pH, mixing among soil layers, and increased soil disturbance. Such changes have been shown to harm native plant species – both herbaceous ones on the forest floor as well as the regeneration of woody vegetation, including trees. See the review just published by Craven et al. 2016 and Hale and Nuzzo references below).

Craven et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of 645 observations in earlier publications. They sought to measure the effects of introduced earthworms on plant diversity, cover of plant functional groups, and cover of native and non-native plants. Sites with a higher the diversity of invading earthworms – with associated variety in behaviors (see below) – had greater declines in plant diversity. Higher earthworm biomass or density did not reduce plant diversity but did change plant community composition: cover of sedges and grasses and non-native plant species significantly increased, and cover of native plant species (of all functional groups) tended to decrease. The increase in non-native plant cover in areas with higher earthworm biomass is thus an example of ‘invasional meltdown’ as propounded by Simberloff and Von Holle in 1999.

Craven et al. 2016 propose several direct and indirect mechanisms by which introduced worms might affect plant species. These include ingestion of seeds or seedlings, burying seeds, and alteration of water or nutrient availability, mycorrhizal associations, and soil structure. European and Asian plant species that co-evolved in the presence of earthworms could better tolerate earthworms’ presence.

Important Questions

Craven et al. 2016 note that the interaction of the invader-related factors with other site-related conditions such as deer browsing, fire history, forest management, and land-use history require further study to disentangle. Many other questions need to be answered, too.

Although Craven et al. (2016) do not specify the geographic range of the studies analyzed, I believe most were conducted in the northern and northeastern regions of the United States and some parts of Canada. It would be interesting to see if these studies’ findings differed from those carried out in Great Smoky Mountains National Park on the Tennessee-North Carolina border. The latter is an area where – unlike the northern states – earthworms were not wiped out by the most recent glaciation. (See references by Bruce Snyder and Jeremy Craft, below.)

The finding that worm species diversity is associated with decreased plant species diversity seems to indicate that worms’ impacts might vary depending on the behavior of the worm in question – especially whether the worms remain on or near the soil surface and — if not — how deeply they burrow. Are studies under way to clarify these differences?

Furthermore, do the impacts of European worms – the subjects of most of the studies carried out in Minnesota, New York, and Pennsylvania – differ substantially from the impacts of Asian earthworms? Or are any differences explained better by the species’ activity in the soil (e.g., depth of burrows) than their origins?

Impacts of earthworms on wildlife are less studied and perhaps less clear. Several studies have focused on salamanders because of their known dependence on leaf litter. In a study of 10 sites in central New York and northeastern Pennsylvania, Maertz et al. 2009 found that salamander abundance declined exponentially with decreasing volume of leaf litter. They suggested that the salamander declines were a response to declines in the abundance of small arthropods, a stable resource.

A study by Ziemba et al. (2016) in Ohio involved Asian worms (genera Amynthas and Metaphire) rather than the European worms most often included in studies carried out in Minnesota, New York, and Pennsylvania. These authors found a complex picture: earthworm abundance was negatively associated with juvenile and male salamander abundance, but had no relationship with female abundance.

Craft (2009) found that reduced leaf litter mass in invaded areas of Great Smoky Mountains National Park diminished habitat for both salamanders and salamander prey.

Others have studied millipedes – a largely unappreciated example of biological diversity in the Southern Appalachian Mountains – in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Snyder and colleagues (2013) found that earthworms in the genus Amynthas altered soils by decreasing the depth of partially decomposed organic horizons and increasing soil aggregation. The result was a significant decrease in millipede abundance and species richness – probably as a result of competition for food.

Results from a study of earthworms’ effects on the Park’s food web by Anita Juen and Daniela Straube, begun in 2010, have not yet been published (pers. comm. from GRSM staff).

Even birds might be affected by worm invasions. One study in Wisconsin found that hermit thrush and ovenbird populations are lower in areas infested by worms. Possible reasons for the decline are that nests (on the ground) are more vulnerable to predation when located in the grasses promoted by worms, and a reduction in invertebrates fed to nestlings.

Expanding Risks

Several non-native earthworm species have been collected (so far) only from greenhouses or other places of indoor cultivation. But can we be sure that they are not being spread to yards, parks, and other places halfway to natural systems through movement of plants and mulch?

Earthworms are extremely difficult to manage once established.

Are these challenges the reasons why few official efforts to control earthworm spread have been adopted? Or is it the animals’ public image – they are widely regarded as “good” critters that enrich the soil and facilitate composting. Or is it that trying to control worms will require enhanced regulation of the nursery and green waste industries?

Amynthes photo; from Wisconsin DNR website

Amynthes photo; from Wisconsin DNR website

Wisconsin Is the Policy Pioneer

Wisconsin stands out for trying to address the issue! The state’s conservation and phytosanitary officials became alarmed when they detected Amynthas species in the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in 2013. This is the site of regular plant sales,a likely pathway for spread. Wisconsin now knows this genus of worms to be present in 21 counties, mainly along urban corridors. They have not yet been found in the state’s forests.

Wisconsin is acting to protect its forests despite Amynthas worms having been present in the United States for over a century: Snyder, Callaham and Hendrix 2010 say several species of Amynthas were documented in Illinois and Mississippi by the 1890’s. Some 15 species are recorded as established and widespread across the eastern United States (Reynolds and Wetzel 2004).

Wisconsin has classified the Amynthas genus as “restricted” – so their movement is now regulated. The risk of spread appears to be greatest through mulch produced from leaves collected in residential communities. The state held a workshop during which the regulated industry developed best management practices to address that risk. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has posted a web page with information about identifying the worms and the BMPs. (Wisconsin DNR has also been a leader in tackling the firewood pathway.) The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture put the worm issue on the agenda of the National Plant Board in August 2016 and urged other states to take action.

The Wisconsin DNR webpage has

- ID cards and other information to aid identification, g., photos of worms and the “coffee ground” soil they create;

- a brochure with the state’s new “best management practices”

- educate yourself and others to recognize jumping worms;

- watch for jumping worms and signs of their presence;

- ARRIVE CLEAN, LEAVE CLEAN – Clean soil and debris from vehicles, equipment and personal gear before moving to and from a work or recreational area;

- only use, sell, plant, purchase or trade landscape and gardening materials and plants that appear to be free of jumping worms; and

- only sell, purchase or trade compost that was heated to appropriate temperatures and duration following protocols that reduce pathogens.

What’s Up Where You Are?

What is your state doing to slow the spread of invasive earthworms?

- Do nursery inspectors look for earthworms when approving plant shipments? Craven et al. 2016 findings re: higher impacts on plants as number of worm species rises demonstrate the importance of slowing spread of new species even into areas that already have some non-native earthworms.

- Are professional associations of nurserymen and green waste recyclers educating their members about the damage caused by invasive earthworms and steps they can take to minimize worms’ spread to new areas?

- Are organizations of anglers and gardeners in your state educating their members about the damage caused by invasive earthworms and steps they can take to minimize worms’ spread to new areas?

- Are ecologists studying earthworm invasion impacts in other parts of the country? In non-forested ecosystems?

- Are conservation organizations initiating or joining outreach efforts?

- Can worm-education efforts be joined with h more robust public and private outreach focused on aquatic invaders, invasive plants, or firewood?

SOURCES

Bohlen, P.J., S. Scheu, C.M. Hale, M.A. McLean, S. Migge, P.M. Groffman, and D. Parkinson. 2004. Non-native invasive earthworms as agents of change in northern temperate forests. Front Ecol Environ 2004; 2(8): 427–435

Craft, J.J. 2009. Effects of an invasive earthworm on plethodontid salamanders in Great Smoky Mountans National Park. Thesis prepared at Western Carolina University.

Craven, D., M.P. Thakur, E.K. Cameron, L.E. Frelich, R.B. Ejour, R.B. Blair, B. Blossey, J. Burtis, A. Choi, A. Davalos, T.J. Fahey, N.A. Fisichelli, K. Gibson, I.T. Handa, K. Hopfensperger, S.R. Loss, V. Nuzzo, J.C. Maerz, T. Sackett, B.C. Scharenbroch, S.M. Smith, M. Vellend, L.G. Umek, and N. Eisenhauer. 2016.The unseen invaders: intro earthworms as drivers of change in plant communities in No Am forests (a meta-analysis). Global Change Biology (2016), doi: 10.1111/gcb.13446 available here.

Hendrix, P.F. 2010. Spatial variability of an invasive earthworm (Amynthas agrestis) population and potential impacts on soil characteristics and millipedes in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA. Biological Invasions DOI 10.1007/s10530-010-9826-4

Maertz, J.C., V. Nuzzo, B. Blossey. 2009. Declines in Woodland Salamander Abundance Associated with Non-Native Earthworm and Plant Invasions. Conservation Biology Volume 23, Issue 4 August 2009 Pages 975–981

Nuzzo, V.A., J.C. Maerz, B. Blossey. 2009. Earthworm Invasion as the Driving Force Behind Plant Invasion and Community Change in Northeastern North American Forests. Conservation Biology Volume 23, Number 4, 966-974.

Simberloff, D. and Von Holle, B. 1999. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biological invasions 1, 21-32

Snyder, B.A., M.A. Callaham, C.N. Lowe, P.F. Hendrix. 2013. Earthworm invasion in North America: food resource competition affects native millipede survival and invasive earthworm reproduction. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 57, 212-216

Ziemba JL, Hickerson C-AM, Anthony CD. 2016. Invasive Asian Earthworms Negatively Impact Keystone Terrestrial Salamanders. PLoS ONE 11(5): e0151591. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151591

See also:

Global picture: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19325931-600-war-of-the-worms/

Great Lakes Wormwatch website: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/worms/research/publications.html

Illinois Natural History Survey webpage: http://wwn.inhs.illinois.edu/~mjwetzel/IllinoisEarthworms.html

Wisconsin DNR http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/invasives/fact/jumpingWorm/index.html

Information on western Canada:

http://ibis.geog.ubc.ca/biodiversity/efauna/EarthwormsofBritishColumbia.html

Native Earthworms of British Columbia Forests: http://www.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/pubwarehouse/pdfs/5102.pdf

Posted by Faith Campbell

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

![PHYTRA_06[1]](http://nivemnic.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PHYTRA_061.jpg)