Introduced wild hogs (Sus scrofa) threaten ecosystems across the continent and on islands ranging from Hawai`i to the Caribbean.

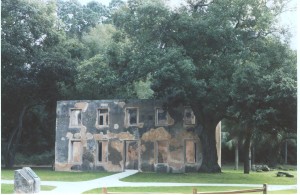

feral hogs in Missouri

feral hogs in Missouri

Pigs are the ultimate survivors – highly adaptable and prolific. Most of the damage is done by their rooting for plant parts and invertebrates in the soil, and by wallowing to cool themselves and fend of biting insects. Depending on soil type (density, moisture level, compaction), pigs may root to depths of three feet below the surface (USDA APHIS EIS).

Feral hogs consume primarily plant matter. They prefer hard mast – e.g., acorns, beechnuts, chestnuts, or hickory nuts. Pigs can be formidable competitors with native wildlife for this nutritious food. Feral hogs also eat algae, fungi, invertebrates such as insects, worms, crustaceans, and bird and reptile eggs. In addition, they feed on small animals, including reptiles, fish, amphibians, ground-nesting birds, and young of wild game and domestic livestock. They even feed on larger animals – although it is not clear whether they kill such animals or only scavenge their carcasses (USDA APHIS EIS).

Since pigs lack sweat glands, they wallow in water and mud to cool off. Some wallow sites are used for years. Adjacent areas are usually denuded of vegetation and the soils are compacted. Wallows are commonly located in or adjacent to riparian or bottomland habitats (USDA APHIS EIS).

Despite the apparent damage, only a few studies address the feral hogs’ impacts on soil structure, chemistry, bulk density and nutrient cycling. The conclusions of those studies are mixed (USDA APHIS EIS).

In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, feral pigs are reported to “plow up” areas in search of bulbs, tubers and wildflowers and to consume small mammals, snakes, mushrooms, bird eggs, and salamanders. (The Smokies are a center of endemism for salamanders.) Wallows are said to contribute significantly to stream sedimentation, thereby harming aquatic life.

Furthermore, feral hogs contribute to both human and animal disease. Their feces contaminate water and soil with coliform bacteria and Giardia which are both a threat to human health. Some of the wild pigs also carry Pseudorabies, a disease that is almost always fatal to mammals, including such important wildlife species as black bear, bobcat, elk, white tailed deer, red fox, grey fox, coyote, mink, and raccoon. Pseudorabies from wild boar can survive in humid air or water for up to seven hours and in plants, soil, and feces for up to 2 days.

Unfortunately, the United States’ population of introduced wild pigs has dramatically increased since 1990. People are to blame.

States with feral hog populations; provided by John Mayer, US Department of Energy, Savannah River National Laboratory

According to John J. Mayer, the number of states with established wild boar populations has risen from 19 in the 1990s to 37. The total number of feral hogs has risen from an estimated 1 to 2 million animals to a range of 4.4 to 11.3 million (Mayer).

The overwhelming majority of the feral hogs is found in only 10 states –AL, AR, CA, FL, GA, LA, MS, OK, SC, TX. Texas has the largest numbers, 30 to 41% of the U.S. total, depending on whether one is counting the states’ animals by mean, maximum, or minimum estimates.

Why have people transported feral pigs to so many new places over the last 20 years? Largely because hunters wanted an exciting game animal to pursue (USDA APHIS EIS; Mayer). In Tennessee, populations of feral swine (probably released by farmers to forage for themselves) were relatively stable and confined to only a few counties from the 1950s through the 1980s. However, since a statewide, year-round, no bag-limits hunting program was instituted in 1999, pig populations have expanded rapidly. In 2011, nearly 70% of counties had pockets of feral swine (USDA APHIS EIS).

But hunting is not an effective means of controlling the animals’ populations and damage. Mayer reports that sport hunters remove about 23% of a wild pig population annually. Models demonstrate that 50 – 75% of a wild pig population must be removed annually, year after year, in order to reduce or eradicate that population (J.J. Mayer pers. comm]

Mayer says there are currently no effective management tools or options to reduce or control feral hog populations in most situations. I note that the Hawaii Volcanoes and Haleakala National parks have been able to eradicate feral pigs through determined efforts.

Missouri is one state that is tackling feral hogs aggressively. In January, the Missouri Conservation Commission approved changes to the Wildlife Code of Missouri that would prohibit the hunting of feral hogs on lands owned, leased, or managed by the Missouri Department of Conservation. A public comment period on the proposed regulation change will run from April 2 through May 1. After considering the citizen input and staff recommendations, the Commission will reach a decision whether to finalize the new regulation – probably in September. (Missouri has quite extensive material on feral hogs posted here

Meanwhile, the Missouri Department of Conservation has reached out to several partners to strengthen its increase the number of feral hog traps it can place and enhance communication to the public. These partners include such agricultural organizations as the Missouri Farm Bureau and Missouri Pork Producers; and such conservation organizations as the National Wild Turkey Federation and two quail associations.

New York has gone farther; it has adopted a policy of eradicating Eurasian wild boar from the state. To achieve this goal, the state in October 2013prohibited importing, breeding, or releasing Eurasian boars. As of September 2015, it has been illegal to possess, sell, distribute, trade or transport Eurasian boars in New York. Hunting or trapping of Eurasian boars is illegal except for law enforcement officers, farmers, and landowners authorized by the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The hunting ban was adopted in order to minimize breakup of sounders so as to facilitate eradication trapping by trained conservation officers. For more information, visit the DEC website.

Sources

Mayer, J.J. 2014. Estimation of the Number of Wild Pigs Found in the Unted States. August 2014 SRNL-STI-2014-00292, Revision 0.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Final Environmental Impact Statement. Feral Swine Damage Management: a National Approach May 27, 2015

Click to access 2015%20Final%20EIS%20Feral%20Swine%20Damage%20Management%20-%20A%20National%20Approach.pdf

Posted by Faith Campbell

PSHB damage to coast live oak;

PSHB damage to coast live oak;

feral hogs in Missouri

feral hogs in Missouri