photo by Nate Siegert

USDA Forest Service has issued its annual summary of the nation’s forest health, based on various data sources.

The report seeks to provide status and trends at the national and regional levels as of 2017. It analyzes drivers of tree mortality including insects and pathogens, fire, and weather (especially drought). The report also discusses plant invasions in forests in the East. There is considerable discussion of emerging methods to improve data collection and analysis. Finally, it includes three case studies to illustrate the power of these approaches for analyzing forest health issues at specific sites:

• Decline of bishop pine (Pinus muricata) stands in California’s northern coastal areas;

• Impacts on naio (Myoporum sandwicense) on Hawaii’s Big Island of the myoporum thrips; and

• Impacts of increasing temperatures on Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) communities.

Tree-Killing Insects and Pathogens

In 2017, the USFS Forest Health Protection (FHP’s) national Insect and Disease Survey (IDS) covered 55.1% of the total forested area of the lower 48 states. In Alaska, surveys covered about 7.3% of the total forested area. In Hawai`i, the surveys covered about 80.1 %.

The FHP program and partners in State agencies identified 63 mortality-causing agents and complexes that cumulatively affect 3.27 million hectares in the lower 48 states – 1.3% of the total 252 million hectares of forested land in these states. They also identified 50 defoliating agents and complexes affecting approximately 2.34 million hectares.

Most of the analyses focus on ecoregions developed by USFS scientists based on concepts put forward by Bailey (1995). Ecoregions are made up of regions with similar geology, climate, soils, potential natural vegetation, and natural communities. The area of the lower 48 states is divided into 190 ecoregions (see Chapter 1, esp. page 7).

Their damage, by type and level, was not evenly spread. Geographic hot spots of forest mortality were associated with bark beetle infestations in the West, and with emerald ash borer and southern pine beetle in the East. Hot spots of defoliation were associated with European gypsy moth and several native insects. Several native insects were the principal agents of defoliation in Alaska. In Hawai`i, about 37,000 hectares of mortality were listed officially as caused by an unknown agent, but the report attributes this mortality to rapid ‘ōhi‘a death.

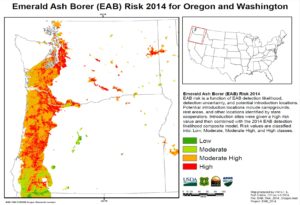

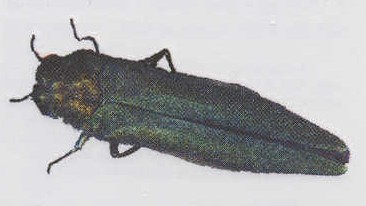

The emerald ash borer was the most widespread single mortality agent in 2017, causing measurable tree mortality on 1.42 million hectares. In the program’s North Central region, 91% of the area suffering tree mortality was associated with the EAB. In one ecoregion – the Lake Whittlesey Glaciolacustrine Plain ecoregion (on the Ohio-Michigan border), about 73% of the mortality was caused by insects, especially the EAB. In a second, the Southwestern Great Lakes Morainal ecoregion (along the western shore of Lake Michigan in Wisconsin and Illinois), a quarter of the surveyed forest was experiencing exacerbated mortality due to EAB. The EAB also is causing mortality across 10,346 ha in the Northeast and more than 5,000 ha in the South.

However, heightened mortality (rates above 1%) in several Great Plains ecoregions were attributed largely to drought – even in the elm-ash-cottonwood forest type. However, such biological factors as oak decline, bur oak blight (Tubakia iowensis), Dutch elm disease, and native pests of ash were also significant. Emerald ash borer is mentioned rarely. I am confused by this finding – perhaps it reflects the fact that EAB has not yet been detected in North Dakota?

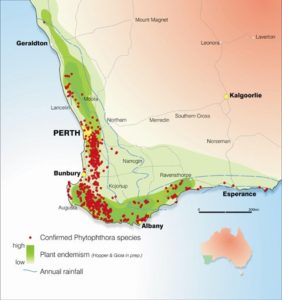

Other non-native pests that affect more than 5,000 ha in the lower 48 states were the Balsam woolly adelgid (20,758 hectares, primarily in the Northeast), beech bark disease (12,222 ha, primarily in the North Central region), oak wilt (9,573 ha, primarily in the North Central region), and sudden oak death (6,335 ha, in California). (All are described here.)

Still, despite the numerous and widespread presence of EAB and other non-native tree-killing insects and pathogens in the Central and Eastern States, in most areas, tree mortality is low relative to tree growth. Indeed, in nearly all the other North Central ecoregions, as well as those in the Northeast and South, 1% or less of the forested area was exposed to mortality agents. Hot spots associated with EAB were detected in Connecticut and eastern Kentucky.

Oak wilt was reported as a mortality agent in Michigan and Texas.

I am confused by the discrepancy between the findings of the Forest Health Protection (FHP’s) national Insect and Disease Survey and studies by other USFS scientists – as reported in earlier blogs. Thus, Randall Morin, speaking at the 81st Northeastern Forest Pest Council in March 2019, reported detecting an approximate 5% increase in mortality – measured by tree volume – nation-wide. The greatest increases in mortality above the background rate was the four-fold increase for redbay and the three-fold increase for ash trees (from 0.8% to 2.7%), beech (from 0.7% to 2.1%), and hemlock (from 0.5% to 1.7%). (The increase for ash was incorrectly stated in my earlier blog).

Other studies by, among others, Guo et al. 2019 and the Potter studies discussed the threat – present and future – rather than current changes in mortality levels. See my blog here.

All note that their estimates are probably underestimates.

All the studies agree that EAB, European gypsy moth, and oak wilt threaten the greatest number of species (Potter et al. 2091b).

However, these reports also note the widespread presence of other damaging invaders – several of which don’t appear in the FHP survey. These include white pine blister rust (present in 94% of the potential hosts’ ranges; 955 counties); and dogwood anthracnose (in 609 counties in the East; plus uncalculated number of counties in the West) (Morin and the western counties were not calculated) (FIA “dashboards”).

photo by F.T. Campbell

Data available from the West are less suited to the kind of analysis the FHP report used (for an explanation, see chapter 5). In the FHP West Coast and Interior West regions, principal mortality agents were bark beetles, drought, and fire. Some ecoregions suffered up to 5% mortality. Using a different measurement tool — annual mortality volume to gross annual volume growth (MRATIO) – the Southern California Mountain and Valley Ecoregion had the highest damage – at 2.50. This was attributed to a combination of prolonged drought, bark beetles, and fire.

Of 50 defoliation agents and complexes across the lower 48, the most widespread was the European gypsy moth. Across the continent, its impacts were detected on 39% of the total forested area of the lower 48 states (913,000 ha). Defoliation was particularly severe in the Northeast Region — again primarily by the European gypsy moth (869,000 ha). Other non-native defoliation agents affecting more than 5,000 ha in the lower 48 were the larch casebearer (25,891 ha in the North Central region, another 7,400 ha in the West Coast region) and winter moth (12,760 ha in the Northeast region). (The last is described here.)

The report concedes that death of tree species that are scattered in multi-species forests, such as most of the victims of non-native forest pests in the East, are not easily detected by the methodology the USFS uses. Examples cited by the report include emerald ash borer, hemlock woolly adelgid, laurel wilt, Dutch elm disease, white pine blister rust, and thousand cankers disease. (All are described here.)

Hence the authors advise decision-makers to use other forest health indicators in addition to this report.

I have already reported on studies by Morin, Liebhold, and colleagues and Kevin Potter and colleagues. Each finds ways to analyze Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data to provide more detail on mortality caused by non-native insects and pathogens.

Invasive Plants

Invasive plants have already invaded a large proportion of rural forest in the East. Christopher Oswalt and colleagues used FIA data to assess the plant invasion status in 13 bioregions covering most of the temperate and boreal forests in the Eastern U.S. I blogged about Oswalt’s studies previously. Their findings are also reported here, in chapter 6:

- Data were analyzed on 71 invasive plant species;

- Half of the total area of 74 forest types was found to be invaded;

Plant invasions are almost twice as likely on privately than publicly owned land. Ownership alone was the deciding factor for the most-invaded forest types.)

The types of forest most heavily invaded were loblolly-shortleaf pine (61%), elm-ash-cottonwood (59%) oak-pine and oak-hickory (each 58%). The forest types least invaded were northern types: spruce-fir (20%), aspen-birch (32%), and maple-beech-birch (34%).

However, several forest type groups were excluded from the study; these included other eastern softwoods; pinyon-juniper; exotic softwoods; other hardwoods; woodland hardwoods; tropical hardwoods; and exotic hardwoods, and Fraser fir.

One-third of publicly owned (federal, state, and local) forest land was invaded, compared to 46% of private corporate forest and 59% of private non-corporate forest.

SOURCES

Bailey, R.G.. 1995. Descriptions of the ecoregions of the United States. 2d ed. Miscellaneous Publication No. 1391. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. 108 p.

Fei, S., R.S. Morin, C.M. Oswalt, and A.M. 2019. Biomass losses resulting from insect and disease invasions in United States forests

Guo, Q., S. Feib, K.M. Potter, A.M. Liebhold, and J. Wenf. 2019. Tree diversity regulates forest pest invasion. PNAS. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1821039116

Morin, R.S., K.W. Gottschalk, M.E. Ostry, A.M. Liebhold. 2018. Regional patterns of declining butternut (Juglans cinerea L.) suggest site characteristics for restoration. Ecology and Evolution.2018;8:546-559

Morin, R. A. Liebhold, S. Pugh, and S. Fie. 2019. Current Status of Hosts and Future Risk of EAB Across the Range of Ash: Online Tools for Broad-Scale Impact Assessment. Presentation at the 81st Northeastern Forest Pest Council, West Chester, PA, March 14, 2019

Potter, K.M., B.S. Crane, W.W. Hargrove. 2017. A US national prioritization framework for tree species vulnerability to climate change. New Forests (2017) 48:275–300 DOI 10.1007/s11056-017-9569-5

Potter, K.M., M.E. Escanferla, R.M. Jetton, and G. Man. 2019a. Important Insect and Disease Threats to United States Tree Species and Geographic Patterns of Their Potential Impacts. Forests. 2019 10 304.

Potter, K.M., M.E. Escanferla, R.M. Jetton, G. Man, and B.S. Crane. 2019b. Prioritizing the conservation needs of United States tree species: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats. Global Ecology and Conservation. (2019)

USDA Forest Service. Forest Health Monitoring: National Status, Trends, and Analysis 2018. General Technical Report SRS-239. June 2019. Editors Kevin M. Potter Barbara L. Conkling

Ailanthus altissima

Ailanthus altissima