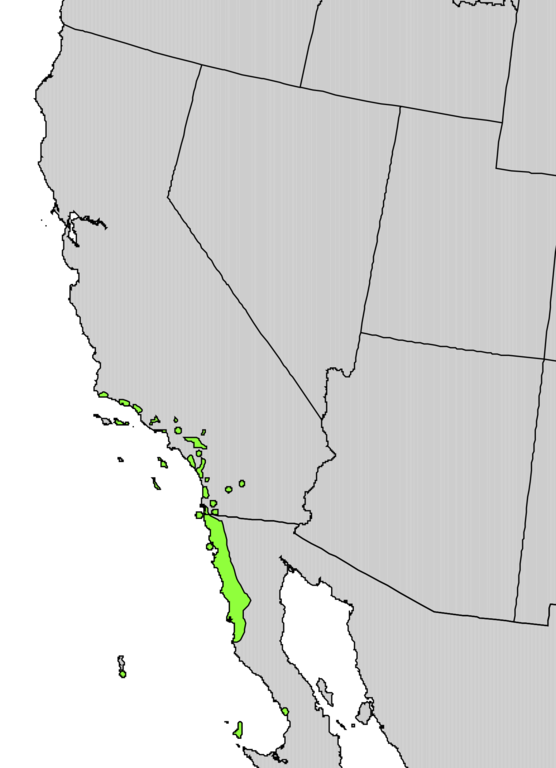

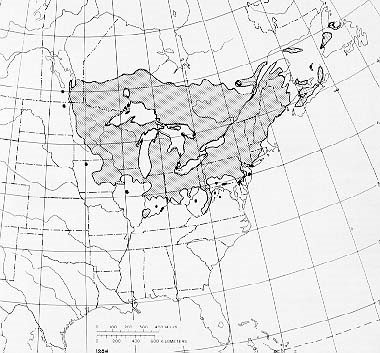

Another unique ecosystem being severely damaged by non-native tree-killing pests are the wetlands dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra). Black ash typically grows in fens, along streams, or in poorly drained areas that often are seasonally flooded. Such swamps stretch from Minnesota to Newfoundland; in the three states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, they cover a total of over 2 million hectares (Kolka et al. 2018).

Recent research allows us to understand the impending loss to these unique ecosystems that will be caused by the emerald ash borer (EAB).

Hydrology is the dominant factor that influences a host of ecosystem functions in black ash wetlands. Water levels are largely determined by a combination of precipitation and evapotranspiration rates. Black ash can thrive in wetter areas than most other tree species (Slesak et al. 2014). Water tables in these swamps are typically above the surface throughout early spring, followed by drawdown below the surface during the growing season with periodic rises following rain events. Water table drawdown coincides with peak evapotranspiration following black ash leaf out, demonstrating the fundamental control that this species has on animal and other plant communities (Kolka et al. 2018; Slesak et al. 2014).

Ecological Importance

Black ash generally dominate the canopy of these wetlands. Ash density can range from about 40% to almost 100%. Several other tree species are present, including northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), red maple (Acer rubrum), American elm (Ulmus americana) (Kolka et al. 2018), quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), American basswood (Tilia americana), and bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) (Slesak et al. 2014), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), and speckled alder (Alnus incana) (Youngquist et al. 2020). Black ash, by maintaining low water levels during the growing season, creates conditions under which these other trees can live but not thrive (summary of study by B.J. Palik, USDA Forest Service, here. Most other species lack the physiological adaptations of black ash or face pathogenic constraints (e.g., Dutch elm disease on American elm Ulmus americana) (Kolka et al. 2018).

Ash trees in these swamps are uneven-aged with canopy tree ages ranging from 130–232 years (Slesak et al. 2014). This complexity provides important habitat for many wildlife species, including ground beetle community assemblages (Kolka et al. 2018) and an abundance of aquatic macroinvertebrates. These are characterized and dominated by mollusks (Sphaeriidae, Lymnaeidae, Physidae), annelids (Lumbriculidae, Hirudinea), caddisflies (Limnephilidae, Leptoceridae), and dipterans (Chironomidae, Culicidae) (Youngquist et al. 2020).

A major concern is that loss of trees – especially ash – might result in open marshes dominated by grasses, especially lake sedge (Carex lacustris). Conversion to sedge-dominated marshes has been observed in areas where trees have been removed as part of experiments to test various ecosystem responses to loss of the ash component (Slesak et al. 2014). Even if other trees took the place of ash, the substitutes might not support the same animal communities (see below).

Impact of Emerald ash borer and loss of black ash

Black ash is highly susceptibility to the EAB (Engelken and McCullough, 2020), so scientists expect severe impacts of the invasion in ash-dominated wetlands and – to a somewhat lesser extent — in forested stream systems’ riparian areas (Engelken and McCullough, 2020). They expect cascading impacts on 1) hydrology; 2) plant communities; 3) wildlife; 4) Native American cultures; and possibly even storage of carbon in vegetation and soils (Kolka et al. 2018).

1) Hydrology

Experiments suggest that loss of ash will cause higher water tables, especially during late summer and fall (Kolka et al 2018). This will result from reductions in evapotranspiration as large trees are replaced by shrubs and grasses (see below) (Kolka et al. 2018; Slesak et al. 2014). The higher water table might be exacerbated if higher annual precipitation levels predicted by climate change models occur. On the other hand, these models also predict a simultaneous increase in longer droughts, which might partially counteract higher precipitation and reduced evapotranspiration (Kolka et al. 2018). If they occur, these possible increases in drought length and frequency might enhance the establishment of less water-tolerant non-ash tree species in former black ash wetlands.

2) Plant Communities

Higher water tables are expected to reduce tree densities and promote conversion to open or shrub-dominated marshes. Several of the possible alternative tree species do not thrive as well as black ash under current conditions (Kolka et al. 2018). However, new hydrologic conditions might make forest restoration even more difficult because herbaceous plants transpire less water than trees, thus exacerbating the rising water tables (Slesak et al. 2014).

In upper Michigan, experiments which killed ash by cutting or girdling did not lead to an increase in growth rates of the remaining canopy species despite the increase in available resources (e.g., sunlight and nutrients) – presumably because of the raised water table (Kolka et al. 2081).

While some studies have found that black ash seedlings and saplings dominated the woody component of the swamp understory up to three years after ash were experimentally removed (Kolka et al. 2018), Engelken and McCullough (2020) found only eight saplings and a single seedling.

Scientists have planted several tree species in experiments to see which might be used to maintain the forested wetlands in the absence of black ash. The results are a confusing mix. Some species grew well once established – but had low levels of seedling establishment. Some trees planted on elevated microsites (hummocks) had the greatest survival and growth rates. (For specific data, see Kolka et al. 2018). A further consideration is tree species’ ability to adapt to warming temperatures already evident and expected to increase in coming decades (Slesak et al. 2014).

Consequently, Slesak et al. (2014) think it is likely that the EAB invasion will alter vegetation dynamics and cause a shift to an altered ecosystem state (e.g., open marsh condition) with higher water tables. They caution that the degree of ecosystem alteration will vary depending on site hydrology, annual precipitation, and period of time necessary for establishment of deeper rooted vegetation.

3) Wildlife

Moreover, any changes in vegetation will also affect the biota in more subtle ways through altered nutrient cycles. Black ash leaf litter is highly nutritious, having some of the highest nitrogen, phosphorus, and cation contents of any hardwood forest species (Kolka et al. 2018). Black ash leaves also decompose faster than most alternative tree species’ leaves (summary of Palik USDA Forest Service, here; Youngquist et al. 2018).

Youngquist et al. (2018) studied litter breakdown, litter nutritional quality, and growth of a representative invertebrate litter feeder – larvae of a shredding caddisfly (Limnephilus indivisus). They found that the larvae’s risk of death increased by a factor of three times or more when caddisflies were fed American elm, balsam poplar, or lake sedge leaves compared to black ash leaf litter. Even when the larvae lived – but matured more slowly because of the lower nutrition value of the leaves – they would still be vulnerable because they must reach metamorphosis before pond dry-down. In any planting done to maintain forested quality of wetlands, need to consider the nutritional quality of the leaf litter provided by replacements. Speckled alder was only apparently acceptable substitute; it was second to black ash in acceptability to caddisflies (Youngquist et al. 2020)

In fact, Youngquist et al. (2020) concluded that plant and detritivore biodiversity loss due to EAB invasion could alter productivity and decomposition at rates comparable to other anthropogenic stressors (e.g., climate change, nutrient pollution, acidification). The result will be altered biogeochemical cycles, resource availability, and plant and animal communities.

Scientists are also concerned about the impact of ash tree mortality on forest connectivity. Conversion of wooded swamps to shrub-and sedge-dominated wetlands will result in the loss of important micro-habitats that are already limited across the forested landscape and may also reduce availability of critical habitat for migrating birds. These changes will exacerbate on-going changes in land use in the Great Lakes region that are causing loss of forest habitat and forest homogenization. As yet, the magnitude of the impact on wildlife is unclear (Kolka et al. 2018).

photo by Faith Campbell

4) Cultural importance – baskets

Native Americans living in the range of black ash have utilized the wood to make baskets and other tools for thousands of years. Baskets had numerous uses, such as packs for carrying items, fish traps, and for preparing food and storing household items. Ash items also had ceremonial uses and they are highly sought as gifts and in trade. The skill needed to select a good tree and work the wood is handed down through the generations and is an important part of tribes’ culture (Benedict 2010).

Discussion of these cultural traditions can be found as Powerpoints here and here.

A video is posted here.

USFS Research Efforts

Concerned by the spread of EAB and probable impact on black ash swamps, the USDA Forest Service has initiated major research studies with the goal of filling in the numerous knowledge gaps and developing management recommendations. A large-scale study using various manipulations to simulate the EAB invasion was initiated in the Chippewa National Forest in northern Minnesota in 2009. A companion study began in the Ottawa National Forest in Michigan in 2010 (Kolka et al. 2018). The Slesak, Youngquist, and Kolka publications cited in this blog report results of some of the studies in this project. Other studies of black ash conditions, including regeneration, at various stages of the EAB invasion wave are being carried out by Deb McCullough, Nate Siegert, and others. They are working at sites from Michigan to New England (D.G. McCullough, pers. comm.).

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report here.

For a great discussion of black ash basketweavers, see Anne Bolen, A Silent Killer: Black Ash Basket Makers are Battling a Voracious Beetle to Keep their Heritage Alive, American Indian Magazine, Spring 2020, available here.

SOURCES

Benedict, M. 2010. Ecology and the Cultural and Economic Importance of Black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh) for Native Americans May 2010 https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5191796.pdf

Engelken, P.J. and D.G McCullough. 2020. Riparian Forest Conditions Along Three Northern Michigan Rivers Following Emerald Ash Borer Invasion. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. Submitted

Kolka, R.K., A.W. D’Amato, J.W. Wagenbrenner, R.A. Slesak, T.G. Pypker, M.B. Youngquist, A.R. Grinde and B.J. Palik. 2018. Review of Ecosystem Level Impacts of Emerald Ash Borer on Black Ash Wetlands: What Does the Future Hold? Forests 2018, 9, 179; doi:10.3390/f9040179 www.mdpi.com/journal/forests

Slesak, R.A., C.F. Lenhart, K.N. Brooks, A.W. D’Amato, and B.J. Palik. 2014. Water table response to harvesting and simulated emerald ash borer mortality in black ash wetlands in MN, USA. Can. J. Forestry. Res. 44:961-968.

Youngquist, M.B., C. Wiley, S.L. Eggert, A.W. D’Amato, B.J. Palik, & R.A. Slesak. 2020. Foundation Species Loss Affects Leaf Breakdown and Aquatic Invertebrate Resource Use in Black Ash Wetlands. Wetlands. Society of Wetland Scientists

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm