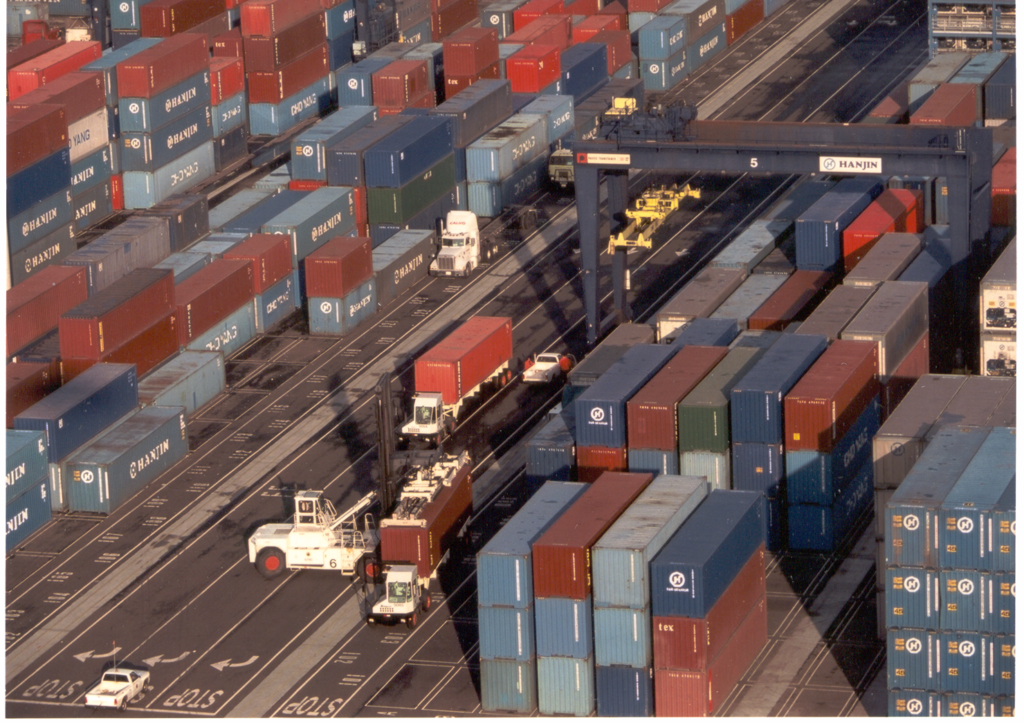

As this blog has repeatedly demonstrated, new non-native forest insects continue to be intercepted at ports-of-entry, including the beetles in the highly-damaging Scolytinae group (wood borers and bark beetles) – despite implementation of international rules to stop them (ISPM#15). Inspection is not an effective preventive measure – although useful as a deterrent when combined with effective requirements for treatment or other measures.

Meanwhile, early detection/rapid response programs are difficult and expensive, so officials need to determine priority targets. There has been considerable effort to develop tools for predicting which types of previously unknown – or poorly known – organisms will cause the most significant damage. Past studies have shown that traits of introduced species have not been strong predictors of impact [Schultz et al. (2019); full citation at end of blog]. Newer studies validate a different approach – focusing on the traits of the host trees. This is, of course, possible only when the probable hosts are known!

The focus on traits of hosts appears to be an application of components of the concept put forward by Lovett et al. in 2006. They found that a pest’s level of impact resulted from a combination of: 1) pest characteristics, i.e., mode of action, host specificity, and virulence; and 2) host characteristics, i.e., its importance in the forest ecosystem, its uniqueness, and its phytosociology (defined as whether the tree grows in pure or mixed stands, its role in succession dynamics, and how efficiently it regenerates; Lovett et al. (2006) looked at a broader suite of impacts, linked to changes in forest composition that result from mortality of the principal hosts.

The on-going project seeks features/traits useful in predicting the impacts of non-native insects on North American trees. [I recognize that it is much more difficult to carry out a statistical study of pathogens – but the impact of several non-native pathogens is so high that we need to try!] In April 2020 I posted a blog summarizing one step in this study [Mech et al. (2019); full citation at the end of this blog], which focused on pests of conifers. The second step – analysis of pests of hardwoods – has now been published [Schultz et al. (2019)]. I look forward to the third component, which will analyze generalists which utilize hosts in more than one angiosperm family or both angiosperms and conifers. (Some prominent examples, e.g., Asian longhorned beetle, the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers, and brown spruce longhorned beetle, are considered “generalists” under the criteria applied in this project.)

Here I briefly recapitulate the findings of Mech et al. (2019) on conifers; report on Schultz et al. (2019) on hardwoods; and note similarities and differences in their findings.

A Quick Recap on Conifers

Mech et al. (2019) analyzed 58 insects that specialize on conifers (for a full discussion, see blog). About half of the approximately 100 conifer species native to North America have been colonized by one or more of these 58 non-native insects. Three-quarters of the affected trees have been attacked by more than one non-native insect. One of the insects attacked 16 novel North American hosts.

Of these 58 insects, only six are causing high impacts, all in the orders Hymenoptera (i.e., sawflies) and Hemiptera (i.e., adelgids, aphids, and scales) which feed on leaves or sap. These six are (1) Adelges piceae—balsam woolly adelgid; (2) Adelges tsugae—hemlock woolly adelgid; (3) Elatobium abietinum—green spruce aphid; (4) Gilpinia hercyniae—European spruce sawfly; (5) Matsucoccus matsumurae—red pine scale; and (6) Pristiphora erichsonii—larch sawfly. The high-impact pests included no wood borers, root feeders, or gall makers.

Mech et al. (2019) evaluated whether the probability of a non-native conifer specialist insect causing high impact on a naïve North American host could be predicted by any of the following characteristics: (a) evolutionary divergence time between native and novel hosts; (b) life history traits of the novel host; (c) evolutionary relationship of the non-native insect to native insects that have coevolved with the shared North American host; and/or (d) the life history traits of the non-native insect.

Major Drivers of Impacts

They found that the major drivers of impact severity for those that feed on foliage and sap (all the high-impact pests) were:

1) Host’s evolutionary history–

The greatest probability of high impact for a leaf-feeding specialist was when North American hosts diverged from a coevolved host of the insect in its native range recently (~1.5–5.0 million years ago [mya]). The divergence time for peak impact was longer for sap‐feeders – (~12–17 mya). The predictive power of the divergence-time factor was stronger for sap-feeders than for leaf feeders.

2) Shade tolerance and drought intolerance – A tree species with greater shade tolerance and lower drought tolerance is more vulnerable to severe impacts. This profile fits most species of Abies, Picea, and Tsuga.

3) Insect evolutionary history – When a non-native insect shares a host with a closely related herbivorous insect native to North America, the invader is slightly less likely to cause severe impacts.

None of the insect life history traits examined, singly or in combination, had predictive value.

Mech et al. (2019) did not address pathogens. However, Beckman et al. (2021) report that only three non-native organisms pose serious threats to the 37 species of Pinus native to the U.S. All are pathogens. White pine blister rust (WPBR) attacks nine species and has caused widespread changes in forest composition in the West. Pine pitch canker is listed as threatening two narrowly endemic pine species (P. radiata and P. muricata). I am surprised that Beckman et al. (2019) indicate that only a lower threat is posed to P. torreyana by this pathogen. Phytophthora root rot (Phytophthora cinnamomi) threatens one widespread pine species (P. echinata).

Note that the conifer genera Mech et al. (2019) determined to best fit one of the predictive factors – shade tolerance – (see above) does not apply to Pinus.

New Study of Hardwoods

The second study – Schultz et al. (2021) – analyzes the traits and factors associated with damaging non-native insects that specialize on a single family of woody angiosperms (= hardwood specialists). This study used the same methodology as Mech et al. (2019) with two exceptions. First, they included consideration of whether the insect was in the subfamily Scolytinae (bark and ambrosia beetles) because of their close association with fungi which are sometimes highly phytopathogenic in novel hosts. Second, they added two host traits not included in the conifer study: ability to resprout and carbon to nitrogen ratio of the aboveground herbaceous material.

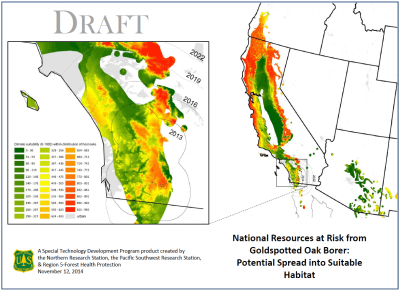

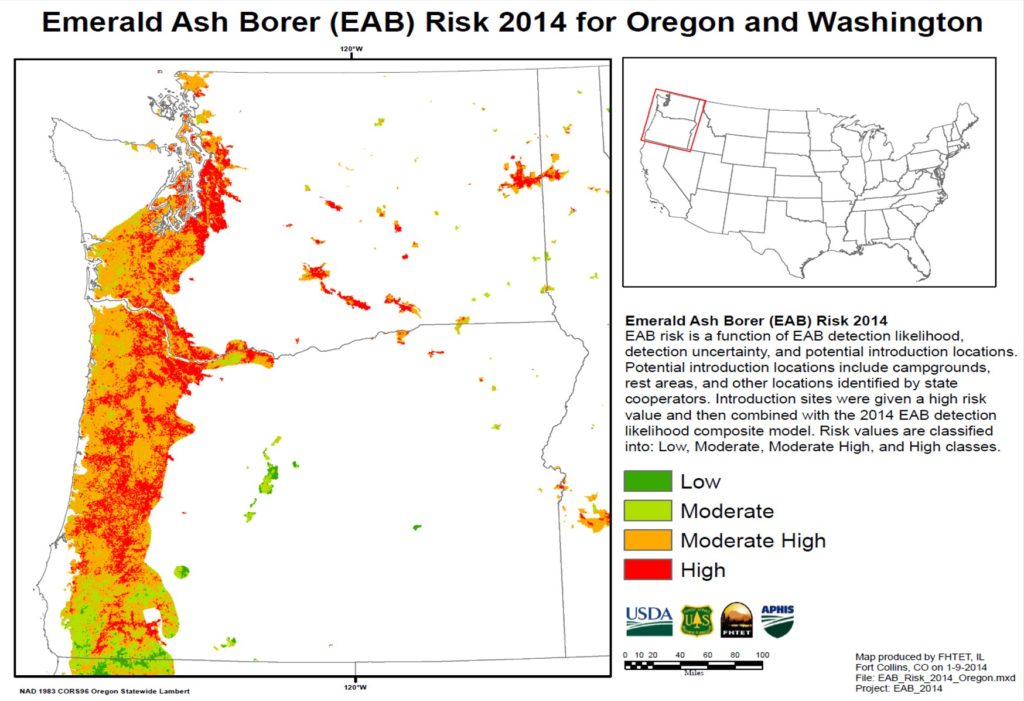

Schultz et al. (2021) developed an initial list of 191 hardwood-specialist insects. 29% were categorized as having no documented effect on hosts. Eight (4.2%) were identified as causing high impact on North American hardwoods = (A) goldspotted oak borer (GSOB) (Agrilus auroguttatus), (B) emerald ash borer (EAB) (Agrilus planipennis), (C) beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga), (D) walnut twig beetle (WTB) (Pityophthorus juglandis), (E) viburnum leaf beetle (Pyrrhalta viburni), (F) erythrina gall wasp (Quadrastichus erythrinae), (G) banded and European elm bark beetles (Scolytus schevyrewi/multistriatus), and (H) redbay ambrosia beetle (RAB) (Xyleborus glabratus). 75% of these high-impact species are beetles. Scale and gall wasp types are represented by one each. [One of these species, Pityophthorus juglandis, vectors thousand cankers disease (TCD) of walnut. As I reported in a recent blog, state phytosanitary agencies have decided that TCD does not pose a significant threat to walnuts and are terminating their quarantines and regulatory programs. I wonder whether this new assessment should prompt the authors to drop it from the list of high-impact pests.]

Information gaps prompted the authors to whittle this list down to 100 insect species for the remainder of the analysis. They identified 151 North American hardwood trees or shrubs used as hosts by the 100 insects, resulting in 292 insect-novel host pairs. Of the 151 host species, 37% hosted more than one non-native insect.

Explaining Impacts and Influential Factors

1) Being a scolytine beetle best explains a specialist insect’s impact on hardwoods. Five (63%) of the eight high-impact species were wood borers, three of them scolytines: S. schevyrewi/multistriatus, X. glabratus, and the possibly misplaced P. juglandis. (Reminder: Mech et al. found that no insect traits predicted impact for conifer specialists).

2) Two factors were moderately explanatory:

- Wood density. Moderate wood density (0.5–0.6 mg/mm3) resulted in an 11–12% chance it would experience high impact from a hardwood specialist; risk decreased if the novel host had lower or higher wood density.

- Divergence time between native and novel hardwood hosts. The greatest probability of high impact was on a novel host that diverged from the host in the insect’s native range ~6 – 16 mya; that risk decreased to nearly zero for hardwood hosts more distantly or closely related. Compared to conifer specialists, this divergence distance was longer than for insects that feed on leaves, shorter than for insects that feed on sap.

3) The impact of specialist insects is not affected by relatednessto native insects on the shared North American hardwood host. Half of the 14 high impact insect-host pairs had a congener present on the shared host.

Reasons for the Influence of These Factors – per Schultz et al. (2019)

- Importance of host evolutionary history. A novel host that has recently diverged from a native host might retain defenses. If those defenses erode over evolutionary time, this would increase the probability that the invading insect will have high impact as it colonizes the novel North American host in a defense-free space. On the other hand, longer evolutionary divergence times might allow the North American plant to change to the point that the introduced insect doesn’t recognize it as a host.

The peak probability of high impact occurred with hosts more distantly related for hardwood (~ 9.5 mya) than for conifer specialists (~ 3.8 mya). The reasons for this difference could be due to the different feeding guilds: 69% of high impact conifer specialist insects are sap-feeders, the rest foliage feeders, while 72% of 25 high impact hardwood specialists are wood borers; 16% folivores, 8% gall makers, 4% sap-feeders.

- Fungal symbionts. A naïve host might lack defenses to either the insect or the fungus – or both.

In North America, the borer-fungi symbiotic relationships is associated with high impact pests of specialist hardwood pests but not conifer pests. However, there are conifer examples on other continents. Possibly North American conifers are at least partially preadapted due to the highly competitive pressures exerted by native scolytines. Conversely, the lower exposure of hardwood hosts to outbreaks of native scolytines might select for less preadaptation.

Another possible explanation is anatomical differences that better allow tree-to-tree below-ground transmission of beetle-vectored phytopathogens in angiosperms (e.g., longer root tracheids, long vessels) than conifers.

- Wood density. Perhaps fast growing, early successional hardwoods with lower wood density are better able to tolerate herbivory, while slow-growing, well-defended, long-lived hardwoods with higher wood density are better able to resist them. Fast growth might also contribute to rapid compartmentalization of infection and decay caused by associated fungi. (Reminder: wood density was not a significant determinant for conifer specialists.)

Schultz et al. (2019) note that their models might need adjustment when new data become available.

SOURCES

Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Pines. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Lovett, G.M., C.D. Canham, M.A. Arthur, K.C., Weathers, and R.D. Fitzhugh. 2006. Forest Ecosystem Responses to Exotic Pests and Pathogens in Eastern North America. BioScience Vol. 56 No. 5 May 2006)

Mech, A.M., K.A. Thomas, T.D. Marsico, D.A. Herms, C.R. Allen, M.P. Ayres, K.J. K. Gandhi, J. Gurevitch, N.P. Havill, R.A. Hufbauer, A.M. Liebhold, K.F. Raffa, A.N. Schulz, D.R. Uden, & P.C. Tobin. 2019. Evolutionary history predicts high-impact invasions by herbivorous insects. Ecol Evol. 2019 Nov; 9(21): 12216–12230.

Schulz, A.N., A.M. Mech, M.P. Ayres, K. J. K. Gandhi, N.P. Havill, D.A. Herms, A.M. Hoover, R.A. Hufbauer, A.M. Liebhold, T.D. Marsico, K.F. Raffa, P.C. Tobin, D.R. Uden, K.A. Thomas. 2021. Predicting non-native insect impact: focusing on the trees to see the forest. Biological Invasions.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm