A few years ago, I posted a blog in which I pointed to a report on South Africa’s response to bioinvasion as a model for the U.S. and other countries. South Africa has published its second report. This report outlines the country’s status as of December 2019 and trends since the first report (i.e. since December 2016). (I describe the report’s findings on South Africa’s invasive species situation in a companion blog.) Again, I find it a good model of how a country should report its invasive species status, efforts, and challenges. In comparison, many U.S. efforts comes up short.

U.S. Reports Need to Be More Comprehensive

The South African report provides a national perspective on all taxa. Various United States agencies have attempted something similar a few times. The report issued by the Office of Technology Assessment in 1993 summarized knowledge of introduced species and evaluated then-current management programs.

The 2018 report by the U.S. Geological Service focused on data: the authors concluded that 11,344 species had been introduced and described the situation in three regions – the “lower 48” states, Alaska, and Hawai`i. However, the USGS did not evaluate programs and policies. The new USDA Forest Service report (Poland et al. 2021) describes taxa and impacts of invasive species in forest and grassland biomes, including associated aquatic systems. Again, it does not evaluate the efficacy of programs and policies.

The biennial national reports required by the Executive Order establishing the National Invasive Species Council (NISC) are most similar to the South African ones in intent. However, none has been comprehensive. For example, the most recent, issued in 2018, strives to raise concern by stating that invasive species effect a wide range of ecosystem services that underpin human well-being and economic growth. Some emphasis is given to damage to infrastructure. The report then sets out priority actions in six areas: leadership and prioritization, coordination, raising awareness, removing barriers, assessing federal capacities, and fostering innovation. NISC also issued a report in 2016 – this one focused on improving early detection and rapid response. NISC posted a useful innovation – a “report card” updating progress on priority actions — in October 2018. It listed whether actions had been completed, were in progress, or were no longer applicable. However, the “report card” gave no explanation of the status of various actions; the most notable omissions concerned the actions dismissed as “not applicable”. Worse, no report cards have been posted since 2018. I doubt if those or any more comprehensive reports will be forthcoming. This reflects the increasing marginalization of NISC. The Council has never had sufficient power to coordinate agencies’ actions, and now barely survives.

U.S. Reports Need to Be More Candid

The authors of the South African report made an impressive commitment to honest evaluation of the country’s gaps, continuing problems, progress, and strengths. As in the first report, they are willing to note shortcomings, even of programs that enjoy broad political support (e.g., the Working for Water program).

It is not clear whether decision-makers have acted — or will act — on the report’s findings. That is true in many countries, including the United States. However, that is separate whether decision-makers have an honest appraisal on which to base action.

Assessment of South Africa’s Invasive Species Programs

Here is a summary of what the authors say about South Africa’s invasive species program. I want to state clearly that my intention is not to criticize South Africa’s efforts. No country has a perfect program, and South Africa faces many challenges. These have been exacerbated by COVD-19.

The report identifies the areas listed below as needing change or improvement.

1) Absence of a comprehensive policy on bioinvasion. Such a policy would provide a vision for what South Africa aspires to achieve, clarify the government’s position, guide decision-makers, and provide a basis for coordinating programs by all affected parties (e.g., including conservation and phytosanitary agencies).

2) As in the first report, the authors call for monitoring program outcomes (results) rather than inputs (money, staffing, etc.) or outputs (e.g., acres treated). The authors also say data must be available for scrutiny. In those cases when data are adequate for assessing programs’ efficacy, they indicate that the control effort is largely ineffective.

3) Inadequate data in several areas. The report notes progress in developing and applying transparent and science-based criteria to species categorization as invasive (as distinct from relying on expert opinion). However, this change is taking time to implement, and sometimes results in species receiving a different rating. [I agree with the report that data gaps undermine understanding of the extent and impacts of bioinvasion, domestic pathways of spread, justification of expenditures, assessment of various programs’ efficacy (individually or overall), priority setting, and identifying changes needed to overcome programs’ weaknesses. However, I think filling these data gaps might demand time and resources that could better be utilized to respond to invasions – even when those invasions are not fully understood.]

4) Funding of bioinvasion programs by the National Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment has been fairly constant over 2012–2019, but this is a decline in real terms. The figure of 1 billion ZAR does not include spending by other government departments, national and provincial conservation bodies, municipalities, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector. Authors of the report expect funding to decrease in the future because of competing needs.

While at least 237 invasive species are under some management (see Table 5.1), funding is heavily skewed – 45% of funding goes to management of one invasive plant (black wattle); 72% to management of 10 species.

5) Need for policies to address the threat emerging from rising trade with other African countries, especially considering the probable adoption of the proposed African Continental Free Trade Area. Under this agreement, imported goods will only be inspected for alien species at the first port of entry, and most African countries have limited inspection capacity. [European pathologists Brasier, Jung, and others have noted the same issue arising in Europe, where imported plants move freely around the European Union once approved for entry by one member state.]

The authors of the South African report say programs’ efficacy would be considerably improved if species and sites were prioritized, and species-specific management plans developed. They warn that, in the absence of planning and prioritization, there is a risk that funding could be diluted by targeting too many species, leading to ineffective control and a concomitant increase in impacts.

In South Africa, regulations, permits, and other measures aimed at regulating legal imports of listed species are increasingly effective. However, there is still insufficient capacity to prevent accidental or intentional illegal introductions of alien species. There is also more enforcement of regulations requiring landowners to control invasive species. Six criminal cases have been filed and – as of December 2019, one conviction (guilty plea) obtained. However, the data do not allow an assessment of the overall level of compliance.

The report found little discernable progress on the proportion of pathways that have formally approved management plans. Management is either absent or ineffective for 61% of pathways. There has been no action to manage the ballast water pathway. On the other hand, in some cases, other laws focus explicitly on pathways, e.g., agricultural produce is regulated under the Agricultural Pests Act of 1983.

During the period December 2016 – December 2019, the Plant Inspection Services tested more than 12,000 plant import samples for quarantine pests and made 62 interceptions. The report calls for more detailed information from the various government departments responsible for managing particular pathways (e.g., the phytosanitary service), and for an assessments of the quality of their interventions.

The number of non-native taxa with some form of management has grown by 40% since December 2016 – although – as I have already noted — spending is highly skewed to a few plant species. The number and extent of site-specific management plans has also increased, apparently largely due to a few large-scale plans developed by private landowners. However, few of these plans have been formally approved by some unspecified overseer.

Citing the strengths and weaknesses described above, the current (second) report downgraded its assessment of governmental programs from “substantial” to “partial”.

Comparison to U.S.

How does the United States measure up on the elements that need change or improvement? I know of no U.S. government report that is as blunt in assessing the efficacy of our programs –individually or as a whole.

Nevertheless, each of the five weaknesses identified for South Africa also exist in the United States:

- Re: lack of a comprehensive policy, I think the U.S. also suffers this absence. This is regrettable since the National Invasive Species Council (NISC) was set up in 1999.

- Re: monitoring outcomes to assess programs’ efficacy, I think U.S. agencies do seem to be more focused on collecting data on programs’ results – see the Forest Service’ budget justification. However, I think too often the data collected focus on inputs and outputs.

- Re: data gaps, I think all countries – including the U.S. — lack data on important aspects of bioinvasion. I differ from the South African report, however, in arguing for funding research aimed at developing responses rather than monitoring to clarify the extent of a specific invasive species. Information that does not lead to action seems to me to be a luxury given the low level of funding.

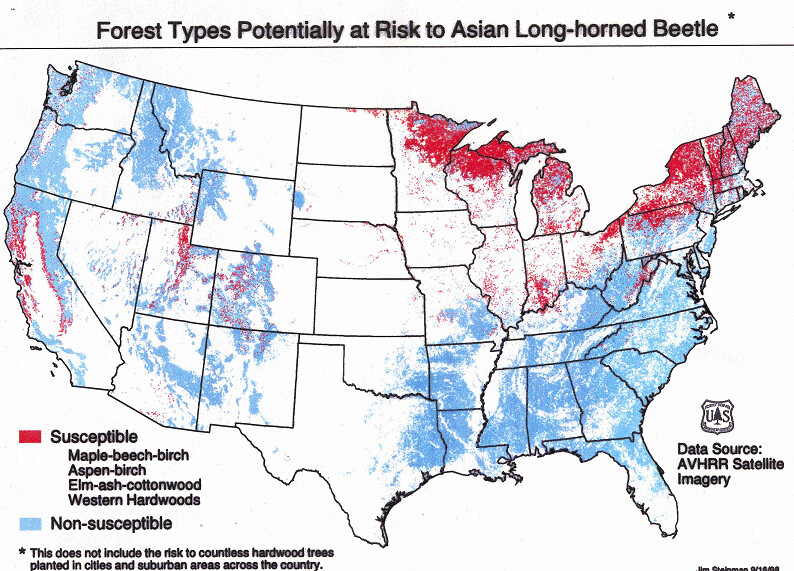

- Re: funding, I find that, despite the existence of NISC, it remains difficult to get an overall picture of U.S federal funding of invasive species programs. Indeed, the cross-cut budget was dropped in 2018 at the Administration’s request. I expect all agencies are under-funded; I have often said so as regards key USDA programs. As in South Africa, funding is skewed to a few species that I think should be lower in priority (e.g., gypsy moth).

- Re: upgrading invasive species programs to counter free-trade policies, I think U.S. trade policies place too high a priority on promoting agricultural exports to the detriment of efforts to prevent forest pest introductions. This imbalance might be present with regard to other taxa and pathways. See Fading Forests II here.

South African and U.S. agencies also face the same over-arching issues. For example, the U.S. priority-setting process seems to be a “black box.” Several USFS scientists (Potter et al. 2019) spent considerable effort to develop a set of criteria for ranking action on tree species that are hosts of damaging introduced pests. Yet there is no evidence that this laudable project influenced priorities for USFS funding.

SOURCES

Poland, T.M., P. Patel-Weynand, D.M Finch, C.F. Miniat, D.C. Hayes, V.M Lopez, editors. 2021. Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States. A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the US Forest Sector. Springer

Potter, K.M., Escanferla, M.E., Jetton, R.M., Man, G., Crane, B.S. 2019. Prioritizing the conservation needs of United States tree species: Evaluating vulnerability to forest P&P threats, Global Ecology and Conservation (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00622.

SANBI and CIB 2020. The status of bioinvasions and their management in South Africa in 2019. pp.71. South African National BD Institute, Kirstenbosch and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch. http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3947613

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm