Kelly Church (Grand Traverse Band Ottawa Chippewa) with baskets she wove from black ash

Kelly Church (Grand Traverse Band Ottawa Chippewa) with baskets she wove from black ash

As you know, in September APHIS published a proposal to alter management of the emerald ash borer (EAB). Under the proposal, APHIS would no longer regulate movement of firewood, nursery stock, or other items that can transport EAB to new areas. Instead, APHIS proposed to rely on biological control to reduce impacts and – possibly – slow EAB’s spread. I have posted two blogs about the weaknesses of the underlying analysis and the decision by the Center for Invasive Species Prevention to oppose the proposal. The proposal, accompanying “regulatory flexibility analysis,” and 150 comments by the public are posted here.

The Don’t Move Firewood program has provided links to the individual organizations’ comments here.

Here I summarize major points made by those commenting on the proposal.

Most state agriculture departments accepted the proposal. Few commented at all, leaving that to the National Plant Board. The NPB letter consisted of only four paragraphs. In contrast, several state forestry agencies commented.

Several organizations, including the National Plant Board and AmericanHort, agreed with APHIS that the quarantine has not worked primarily because detection tools are so poor. As a result, EAB is able to firmly establish for several years and spread in a new area before authorities detect it and take action.

It is clear from the comments that deregulating EAB might save APHIS money and effort, but the action will exacerbate the already substantial burden on many other U.S. entities – ranging from federal agencies such as USDA Forest Service and National Park Service to homeowners; woodlot owners to (potentially) exporters of all sorts of products; to Native Americans. The economic components of this potential burden surely deserve more serious evaluation as required under several Executive orders.

Comments Categorized

1) The quarantine has slowed the spread of EAB and it remains valuable in granting communities time to prepare

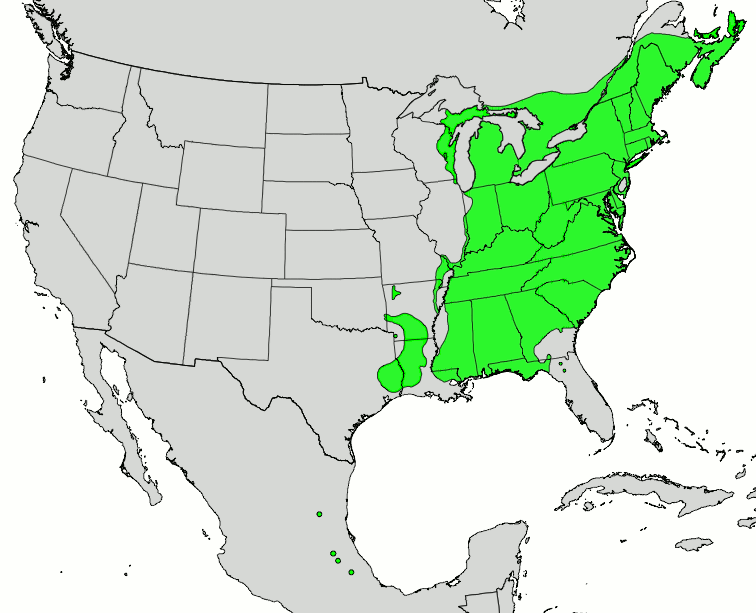

Several of the commenters wished to counter the proposal’s inference that quarantines had failed; rather, they insisted that quarantine has slowed spread of the EAB and that this strategy is still valuable because it gives un-infested areas more time to prepare. Those voicing this view included the National Association of State Foresters; Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation; Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Wisconsin; several bands of Native Americans in Maine (Houlton Band, Penobscot, an individual member of the Penobscot); The Nature Conservancy; a man who is both park superintendent for the City of Kalispell, Montana and Chair of the Montana Urban and Community Forestry Association; three local conservancies in Oregon (West Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District; Four-County Cooperative Weed Management Area from Clackamas, Clark, Multnomah and Washington counties in the greater Portland Metro area; Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District); Jefferson County Colorado Invasive Species Management team; Maine Mountain Collaborative; Blue Hill Heritage Trust of Maine; a small woodland owner in Maine; and a Professor in the School of Forest Resources at the University of Maine.

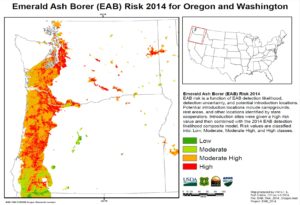

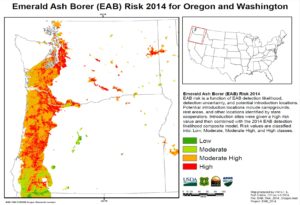

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division opposed the APHIS proposal. The Division noted that EAB spread in the east was facilitated greatly by the continuity of ash habitats whereas ash habitats are much more patchy in the West. Given this situation, human transport is the most likely means by which EAB will reach the West – either from infested portions of the U.S. or via trans-Pacific trade.

A few entities that supported APHIS’ proposal – e.g., the Southern Group of State Foresters and – in a separate letter – Texas Forest Service – also said the quarantine had been helpful.

As The Nature Conservancy said in its comments, the quarantine effectively limits two of the most important pathways, firewood and nursery stock. The result has been to protect much of the country from the pest and buying time to develop mitigation measures.

2) APHIS’ dismissal of quarantine is a worrying message (see also discussion of firewood below)

Several of the commenters expressed concern that APHIS too curtly dismissed the value of quarantine – both as it functioned to slow spread of EAB and as a tool used against a wide range of pests. Commenters raising issues about the proposal’s apparent undermining of quarantine as a strategy included the Kansas Forest Service; Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets and the Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation; and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry. The Vermont and Wisconsin agencies asked APHIS to clarify to affected parties what it expects to achieve by the proposed deregulation. The Fond du Lac Band of Chippewa warned that the public might interpret the dropping of regulations as signaling that EAB is no longer important.

Five organizations unified under the banner of the Coalition Against Forest Pests noted that APHIS had set a precedent of dropping regulations when quarantines appear to fail.

A subset of these comments focused on a lack of clarity by APHIS as to its future strategy.

Several commenters said that APHIS had not outlined a coherent strategy for the future. The Kansas Forest Service even called the proposal an agency “exit strategy” rather than a coherent plan. Others raising this issue included the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Department of Game, Fish and Parks; and the Coalition Against Forest Pests. Maine noted that the proposal would shift the burden of regulation to the states. Maine and South Dakota said that APHIS, as the responsible federal regulatory agency, should provide a clear and consistent process for regulation of potentially infested products across state lines.

The Tennessee Forest Health Coordinator called for an analysis of EAB program successes that might point to ways in which APHIS could support alternative strategies. A professor of forestry in Maine said APHIS should evaluate and assess techniques specifically to optimize the effectiveness of education and outreach.

Among entities which supported APHIS’ proposed new approach, the Southern Group of State Foresters, Texas Forest Service, and two Vermont agencies – Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets and the Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation – urged APHIS to champion a national, multi-agency approach to managing EAB, including creation of a national, voluntary treatment standard and label for firewood; redirecting all savings to research & management – including state surveys. These groups also advocated funding increases for APHIS, the USDA Forest Service, and state EAB programs; and support for states to carry out their enlarged responsibilities for survey, outreach, education, and assistance to affected parties.

The Vermont agencies wrote that EAB “is a nationally significant pest, … which warrants a significant federal role.” Because EAB impacts on communities, forest health, and the forest economy continue to expand, a decision to discontinue regulatory activities should be accompanied by increased federal support for research and management.

The National Association of State Foresters also called for APHIS to champion a national, multi-agency approach, with a somewhat longer list of components. These should include support state research and management efforts, the biocontrol program, identifying genetic strains of ash trees that are resistant to EAB, maintain national treatment criteria for wood products (including firewood), and reconvene the National Firewood Task Force. NASF also urged the USDA Forest Service to develop a cooperative management program to sustain and replace ash trees killed by EAB.

Dr. David Orwig of Harvard Forest also called for funding not just biocontrol but also research areas like silviculture, chemical control, ash utilization, and management guidelines.

This pattern of asking for continued or expanded federal engagement – beyond biocontrol – is quite apparent. Some entitites that said they supported APHIS’ proposal nevertheless called for the agency to continue detection and response components of the program – expressly contrary to the proposal itself.

Thus, AmericanHort, the two Vermont agencies, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry, and two Maine departments called for APHIS to continue or increase its engagement in EAB detection and other management activities – including biocontrol, outreach to explain the change in strategy, and engaging the National Park Service and Forest Service in promulgating a consistent firewood policy.

Others who asked for similar commitments were straightforward in opposing the proposal. Thus the North Dakota Department of Agriculture and North Dakota Forest Service – in separate letters – asked that APHIS continue to provide resources to help states monitor EAB presence and respond to any new detections. The Oregon Department of Forestry asked that federal agencies continue to fund research and development of early detection and rapid response strategies for EAB; conservation of ash genetic resources and promotion of natural resistance; research on uses of dead ash; as well as classical biocontrol once EAB is established in a new area.

Several commenters said that they had considered APHIS to be a critically important partner in countering the EAB and were disappointed that the agency is backing away. Native Americans in particular considered the proposal to be a betrayal of the Federal government’s treaty responsibilities vis a vis recognized tribes. The Fond du Lac Band of Wisconsin wrote that upholding a federal EAB regulation is vital to the protections of important cultural and natural resources both on the Reservation and within territories ceded to the Band by several 19th Century treaties. The tribe cited EO 13175 issued by President Clinton. The Houlton Band of Maine said APHIS has a mission to defend federally recognized tribes against invasive species. The federal government should not make a decision so contrary to its fiduciary trust responsibility to federally recognized tribes.

3) Need for continued APHIS leadership on firewood regulation

The importance of APHIS continuing to lead national efforts to curtail spread of EAB (and other pests) through careless movement of infested firewood was stressed by many commenters. Voicing this need were many of the entities which opposed the proposal, including Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation; Southern Group of State Foresters; Texas Forest Service; the two Vermont agencies; The Nature Conservancy; and the National Association of State Foresters. As noted above, the NASF, Southern Group, Texas, and Vermont all said APHIS should support creation of a national, voluntary treatment standard & label for firewood. TNC said eliminating the EAB quarantine – the best known and understood firewood regulation – will exacerbate difficulties of outreach. Public outreach and education work best when they are backed up by core consistent rules. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation and NASF called for reinstating the National Firewood Task Force (which APHIS led in 2009-2010).

Several entities that supported the proposal also called for continued APHIS engagement on firewood. One, the Wisconsin DNR Division of Forestry, urged APHIS to work with the National Park Service and Forest Service to create a consistent firewood policy. A second, the NPB, noted that it is developing guidance to states interested in initiating regulations, best management practices, or outreach programs. The NBP added that it welcomes any assistance from APHIS.

As The Nature Conservancy and Tennessee Forest Health Coordinator pointed out, the firewood effort – federal regulations, state regulations, education and outreach under the “Don’t Move Firewood” campaign – all helped curb movement of several tree-killing pests, not just EAB.

4) Others Pointed Out the Importance of Consistent Regulations to Keep Markets Open

A smaller number of entities addressed the similar importance of consistent rules governing interstate and US-Canadian trade in other types of vectors that can transport EAB and which are to be deregulated under the proposal. These included the NASF. Several private groups from Maine and the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry noted the importance of reaching agreement with Canada, which is a major market for their wood products. The two South Dakota departments also expressed concerns.

The National Wooden Pallet and Container Association raised the prospect of truly tremendous disruption of trade. At present, the United States and Canada exempt wood packaging originating in either country from requirements that it be treated in accordance with international standards (ISPM No. 15). Canada has many reasons to fear that crates and pallets carrying exports from the U.S. might be infested by EAB once APHIS stops enforcing quarantine regulations. If Canada responds by ending the exemption and requiring wood packaging from the U.S. to comply with ISPM#15, that action would affect a wide range of U.S. exports – from fruits to auto parts. In 2017, the U.S. exported $282 billion worth of goods to Canada (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative)

5) The Economic Analysis Underlying the Proposal was Inadequate

Several commenters criticized the adequacy of the economic analysis. The most specific criticisms were put forward by the California Forest Pest Council; CISP; the five organizations commenting under the banner of the Coalition Against Forest Pests; and the National Wooden Pallet and Container Association. The latter two cited specific Executive orders and the Paperwork Reduction Act in calling for a review of the proposal by the Office of Management and Budget & USDA Office of General Counsel to reassess whether it meets the conditions for the reduced economic analysis. As noted above, the NWPCA mentioned specifically a fear that Canada might discontinue the mutual exemption under which wood packaging may move between the two countries without being treated in accordance with ISPM#15. The possibility of such an action would certainly push the proposal over the $100 million threshold for completing much more rigorous economic analyses.

Other economic concerns not adequately addressed in the view of the commenters relate to costs arising earlier due to the faster spread of EAB to un-infested western states. Costs imposed earlier than would otherwise be the case are considered relevant in regulatory decisions. Furthermore, businesses in these and possibly other states will face new regulations adopted by states to fill the void left by federal deregulation. Finally, the lack of consistency arising from separate state regulations will impede interstate or US-Canada commerce.

Non-regulatory costs – death of trees and associated removal costs – costs to the forest industry, plus municipalities and home owners in areas not currently affected by infestation – were also not discussed in the proposal.

Several commenters said that APHIS had underestimated the ecological and cultural values threatened by spread of EAB. These included the Fond du Lac Band, Penobscot band, TNC, the Oregon soil conservation district and weed management area; Maine Mountain Collaborative and Woodland Owners, as well as several individuals.

The Nature Conservancy noted that three-quarters of the native ash range of the conterminous United States and 14 of vulnerable species in the U.S. and Mexico are still free of EAB as a result of the quarantine.

A Minnesota community’s Parks Commission noted that loss of trees to EAB can lead to other problems and costs. Consequently, the goal of “saving money” will not be achieved. In short, EAB-caused tree mortality “affects communities, including residents, homeowners, and taxpayers. Funding should be directed both to slowing the spread of the pest and to treatment of affected trees.”

A small woodland owner in Maine asked why APHIS did not evaluate economic impacts to landowners & municipalities.

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division added that pesticides used to control EAB might cause negative impacts in riparian and aquatic environments.

6) Several Commenters questioned whether freed-up funds would support biocontrol – or whether they should

As noted in my earlier blogs, there are questions about whether biocontrol will be efficacious in protecting forests across the continent. CAFP echoed these questions. Blue Hill Heritage Trust of Maine called biocontrol experimental.

The Fond du Lac Band pointed out that most tribes don’t accept biocontrol on their reservations – so spending all available funds on this approach doesn’t help Native Americans.

The Maine government and the Penobscot Band of Maine expressed doubt that increased funding would actually materialize.

7) Comments that do not fit neatly into these categories.

The California Department of Agriculture said that it intends to promulgate a state exterior quarantine to protect its agriculture (olive trees are hosts of EAB) and environment.

The South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Department of Game, Fish and Parks concluded that interstate regulatory options should be a higher priority than other methods of control.

The Houlton Band of Maine said that maintaining the domestic quarantine is the only federal action that can adequately address the universally agreed fact that human activities cause the rapid spread of EAB.

The Western Governors Association described the region’s vulnerability to EAB spread and, citing recent Association policy resolutions, said a decision of this magnitude should be made only after substantive consultation with Western Governors.

The National Association of State Foresters pointed out that a decline in federal funding for EAB detection surveys will significantly reduce state forestry agencies’ capacity to monitor and respond to EAB spread.

The Jefferson County, Colorado Invasive Species Management team recommended retaining the quarantine using either the 100th Meridian or Continental Divide as the containment boundary. It cited as a justifications the “culture of vigilance” created by strong quarantines. This vigilance saves financial resources and protects natural and agricultural resources.

Finally, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa said that abandoning methods that are in place for the prevention of EAB’s spread, such as federal and state quarantines, and favoring only options that focus on rehabilitating a site after it has undergone a severe infestation, presents a large and unnecessary ecological risk. Invasive species programs have always focused on “prevention” being the key.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.