As readers of my blogs know, I wish to prevent introduction and spread of tree-killing insects and pathogens and advocate tighter and more pro-active regulation as the most promising approach. I cannot claim to have had great success.

Of course, international trade agreements have powerful defenders and the benefit of inertia. And in any case, prevention will be enhanced by improving the accuracy of predictions as to which specific pests are likely to cause significant damage, which are likely to have little impact in a naïve ecosystem. This knowledge would allow countries to can then focus their prevention, containment, and eradication efforts on this smaller number of organisms.

I applaud a group of eminent forest entomologists and pathologists’ recent analysis of widely-used predictive methods’ efficacy [see Raffa et al.; full citation at the end of this blog]. I am particularly glad that they have included pathogens, not just insects. See earlier blogs here, here, here, and here.

I review their findings in some detail in order to demonstrate their importance. National and international phytosanitary agencies need to incorporate this information and adopt new strategies to carry out their duty to protect Earth’s forests from devastation by introduced pests.

Raffa et al. note the usual challenges to plant health officials:

- the high volumes of international trade that can transport tree-killing pests;

- the high diversity of possible pest taxa, exacerbated by the lack of knowledge about many of them, especially pathogens;

- the restrictions on precautionary approaches imposed by the World Trade Organization’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (the international phytosanitary system) – here, here, and here.

- the high cost and frequent failure of control efforts.

The Four Approaches to Predicting Damaging Invaders

At present, four approaches are widely used to predict behavior of a species introduced to a naïve environment:

(1) pest status of the organism in its native or previously invaded regions;

(2) statistical patterns of traits and gene sequences associated with high-impact pests;

(3) sentinel plantings to expose trees to novel pests; and

(4) laboratory tests of detached plant parts or seedlings under controlled conditions.

Raffa et al. first identify each method’s underlying assumptions, then discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each approach for addressing three categories of biological factors that they believe explain why some organisms that are relatively benign, sparse, or unknown in their native region become highly damaging in naïve regions:

(1) the lack of effective natural enemies in the new region compared with the community of predators, parasites, pathogens, and competitors in the historical region (i.e., the loss of top-down control);

(2) the lack of evolutionary adaptation by naïve trees in the new region compared with long-term native interactions that select for effective defenses or tolerance (i.e., the loss of bottom-up control); and

(3) novel insect–microbe associations formed in invaded regions in which one or both members of the complex are non-native, resulting in increased vectoring of or infection courts for disease-causing pathogens (i.e., novel symbioses). I summarize these findings in some detail later in this blog.

Most important, Raffa et al. say none of these four predictive approaches can, by itself, provide a sufficiently high level of combined precision and generality to be useful in predictions. Therefore, Raffa et al. outline a framework for applying the strengths of the several approaches (see Figure 4). The framework can also be updated to address the challenges posed by global climate change.

Raffa et al. repeatedly note that lack of information about pests undercuts evaluation efforts. This is especially true for pathogens and the processes determine which microbes that are innocuous symbionts in co-evolved hosts become damaging pathogens when introduced to naïve hosts in new ecosystems.

Findings in Brief

Raffa et al. found that:

- Previous pest history in invaded environments provides greater predictive power than population dynamics in the organism’s native regions.

- Models comparing pest–host interactions across taxa are more predictive when they incorporate phylogenies of both pest and host. Traits better predict a pest’s likelihood of transport and establishment than its impact.

- Sentinel plantings are most applicable for pests that are not primarily limited to older trees. Ex patria sentinel plantations are more likely to detect pest species liberated by loss of bottom-up controls than top-down controls, i.e., most fungi and woodborers but not insect defoliators.

- Laboratory tests are most promising for pest species whose performance on seedlings and detached parts (e.g., leaves) accurately reflects their performance on live mature trees. They are thus better at predicting impacts of insect folivores and sap feeders than woodborers or vascular wilt pathogens.

Raffa et al. also ask some fundamental questions:

- How realistic is it to expect reliable predictions, given the uniqueness of each biotic system?

- When should negative data – lack of data showing a species is invasive – justify decisions not to act? Especially when there are so many data gaps?

- Who should make decisions about whether to act? How should the varying values of different social sectors be incorporated into decisions?

Raffa et al. identify critical areas for improved understanding:

1) Statistical tools and estimates of sample size needed for reliable forecasts by the various approaches.

2) Reliability, breadth, and efficiency of bioassays.

3) Processes by which some microorganisms transition from saprophytic to pathogenic lifestyles.

4) Procedures for scaling up results from bioassays and plantings to ecosystem- and landscape-level dynamics.

5) Targetting and synergizing predictive approaches and methods for more rapid and complete information transfer across jurisdictional boundaries.

I am struck by two generalizations:

- While most introduced forest insects are first detected in urban areas, introduced pathogens are more commonly detected in forests. I suggest that more intensive surveys of urban trees and “sentinel gardens” might result in detection of pathogens before they reach the forest.

- Enemy release is rarely documented as the primary basis for pathogens that cause little or no impact in their native region but become damaging in an introduced region. Enemy release appears generally more important with folivores and sap feeders than with woodborers.

Detailed Evaluation of Predictive Methodologies

- Empirical assessment of pest status in previously occupied habitats

This is the most commonly applied method now, partly because it seems to follow logically from the World Trade Organization’s requirement that national governments provide scientific evidence of risk to justify adopting phytosanitary measures. The underlying assumption is that species that have caused damage in either their native or previously invaded ranges are those most likely to cause damage if introduced elsewhere. The corollary is that species that have not previously caused damage are unlikely to cause significant harm in a new ecosystem.

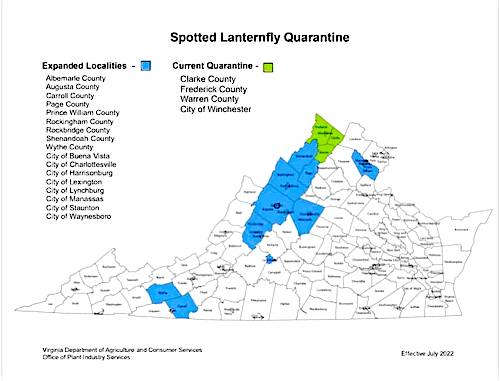

As noted above, Raffa et al. found that a species’ damaging activity in a previously invaded area can help indicate likely pest status in other regions. However, its status — pest or not — in its native range is not predictive. See Table 1 for numerous examples of both pests and non-pests. For example, Lymantria dispar has proved damaging in both native and introduced ranges. Ips typographus has not invaded new territories despite being damaging in its nature range and frequently being transported in wood. White pine blister rust is not an important mortality source on native species in its native range but is extremely damaging in North America.

Raffa et al. also note the importance of whether effective detection and management strategies exist in determining a pest’s impact ranking. Insects are more easily detected than pathogens; some respond to long distance attractants such as pheromones or plant volatiles. These methods can include insect vectors of damaging pathogens.

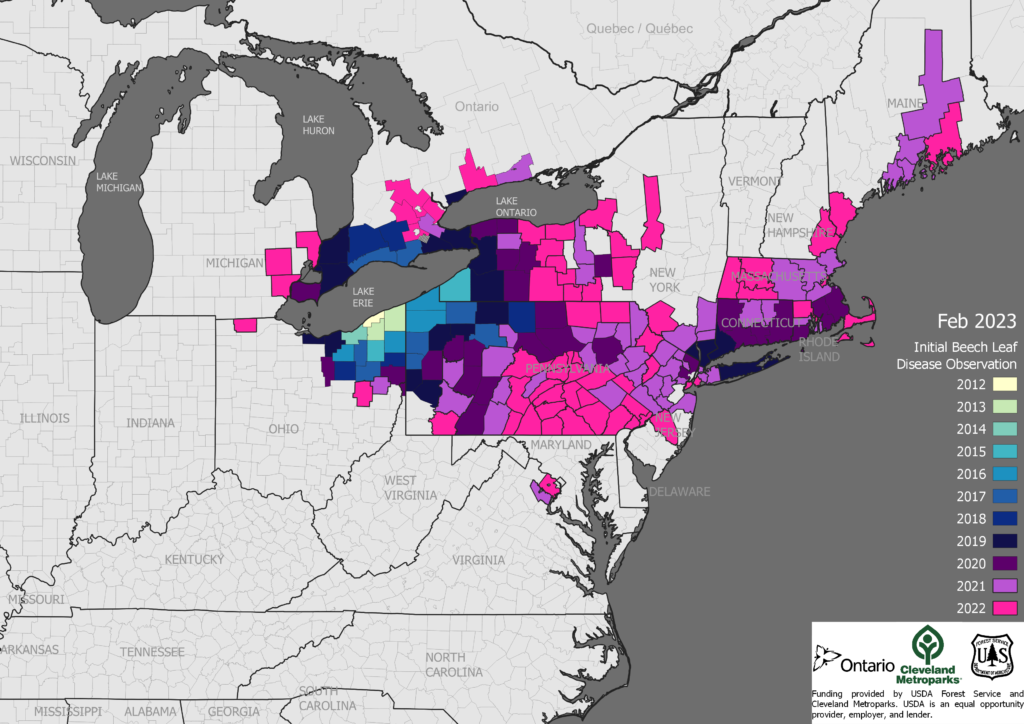

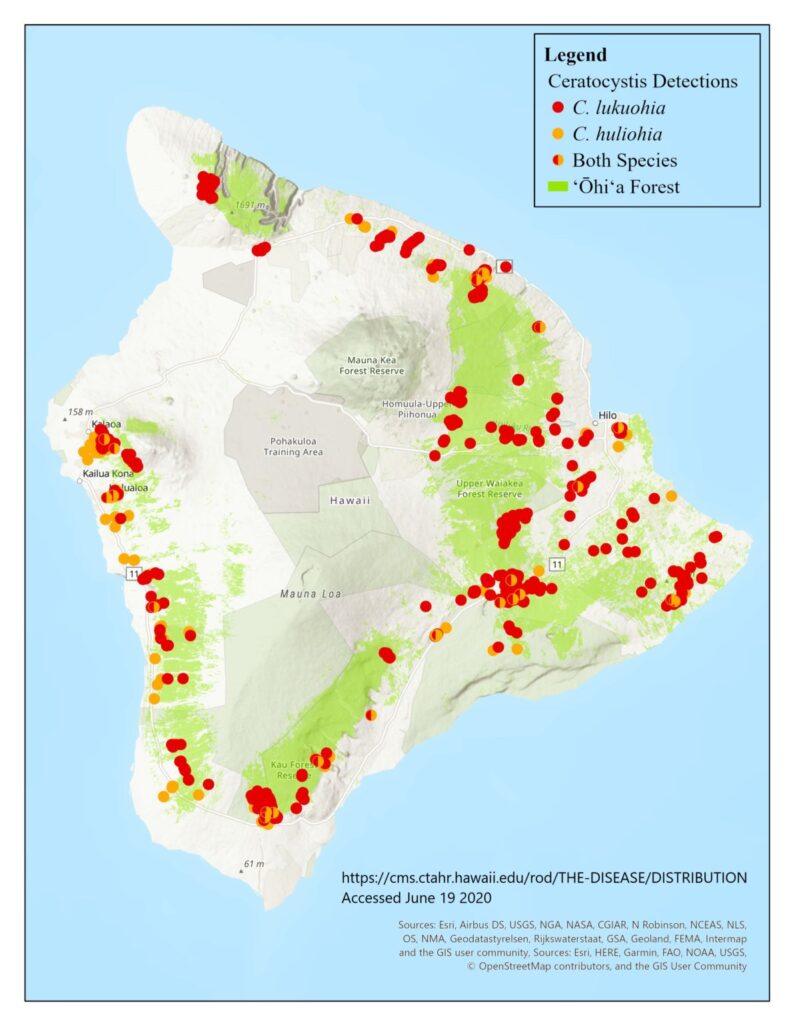

Re: the difficulty of assessing insect–microbe associations, they name several examples of symbionts which have caused widespread damage to naïve hosts: laurel wilt in North America; Sirex noctilio and Amylosterum areolatum around the Southern Hemisphere; Monochamus spp. and Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Asian and European pines. Dutch elm disease illustrates a widespread epidemic caused by replacement of a nonaggressive native microorganism in an existing association with a non-native pathogen. Beech bark disease resulted from independent co-occurrence of an otherwise harmless fungus and harmless insect.

In sum, “watch” lists are disappointingly poor at identifying species that are largely benign in their native region but become pests when transported to naive ecosystems. Many of our most damaging pests are in this group. Raffa et al. note that this is not surprising because naïve systems lack the very powerful top-down, bottom-up, and lateral forces that suppress pests’ populations in co-adapted system. Countries often try to overcome this uncertainty by shifting to pathway mitigation and other “horizontal measures” – as I have often advocated. Raffa et al. emphasize that such approaches are costly to implement and constrain free trade.

- Predictive models based on traits of pests and hosts

Predictive models provide the most all-encompassing and logistically adaptable of the forecasting approaches. Typically, models consider various components of risk, e.g. probability of transport, probability of establishment, anticipated level of damage.

The overriding assumption is that patterns emerging from either previous invasions or basic biological relationships can provide reliable predictions of impacts that might result from future invasions. However, Raffa et al. note that the models’ reliability and specificity are hampered by small sample sizes and data gaps.

They found that specific life history traits have proved to be more predictive of insect — and to a lesser extent fungal – establishment than of impact. Earlier studies [Mech et al. (2019) and Schulz et al. (2021)] found no association between life history traits and impacts for either conifer-feeding or angiosperm-feeding insects.

Some traits of pathogens have been linked to invasion success, e.g., dispersal distance, type of reproduction, spore characteristics, and some temperature characteristics for growth and parasitic specialization. Raffa et al. say that root-infecting oomycete pathogens have a broader host range and invasive range than those that attack aboveground parts. Oomycetes that grow faster and produce thick-walled resting structures have broader host ranges. Phenotypic plasticity is also important. Raffa et al. say that those organisms that require alternate hosts can be limited in their ability to establish. However, they don’t mention that – once introduced — they can have huge impacts, as the example of white pine blister rust illustrates.

Raffa et al. say that phylogenetic distance of native and introduced hosts is more predictive for foliar ascomycetes than for basidiomycete and oomycete pathogens with broad host ranges. They suggest predictive ability can be improved by incorporating other factors, e.g., feeding guild. They note that the findings of Mech et al. and Schulz et al. (see links above) show the importance of both host associations with pests and phylogenetic relationships between native and naïve hosts for predicting impacts.

Geography is important: while there is a greater chance of Northern Hemisphere pests invading in the same hemisphere, this is not universal, as shown by Sirex (of course, the woodwasp is attacking hosts native to the Northern Hemisphere – pines).

Genomic analyses have been used more often with pathogens. There are two general approaches:

1) Comparing the genomes of different species to identify the determinants associated with certain traits or lifestyles. For example, a post hoc analysis of the genus Cryphonectria could distinguish nonpathogenic species from the chestnut blight fungus C. parasitica.

2) Using genomic variation within a single species to identify markers associated with traits. Genome sequencing of a worldwide collection of the pathogens that cause Dutch elm disease revealed that some genome regions that originated from hybridization between fungal species contained genes involved in host–pathogen interactions and reproduction, such as enhanced pathogenicity and growth rate.

Raffa et al. point out that the growth of databases will facilitate genomic approaches to identify important invasiveness and impact traits, such as sporulation, sexual reproduction, and host specificity.

At present, Raffa et al. believe that models based on traits, phylogeny, and genomics offer potential for a rapid first pass to predicting levels of pest damage. However, assessors must first have a list of candidate pest species and detailed information about each. Plus there is still too much uncertainty to rely exclusively on the models.

- Sentinel trees

Raffa et al. say that sentinel trees can potentially provide the most direct tests of tree susceptibility and the putative impact of introduced pests. Three types of plantations offer different types of information:

- In patria sentinels [= sentinel nurseries] = native trees strategically located in an exporting country and exposed to native pests. The intention is to detect problematic hitchhikers before they are transported to a new region. These plantings are useful for commodity risk assessment. However, all the taxa associated with the sentinel trees must be identified to ascertain whether they can become a threat to plants in the new ecosystem.

- Ex patria plantings [= sentinel plantations] = trees from an importing country are planted in an exporting country with the aim of assessing new pest–host associations. These plantings are most useful for identifying threats that arise primarily from lack of coevolved host tree resistance (i.e., loss of bottom-up control). They cannot predict the effects of lack of co-adapted natural enemies in the importing region (i.e., loss of top-down control). Plantings are thus more helpful in predicting impacts by pathogens and woodborers than folivores and sap feeders. However, ex patria plantings cannot predict pest problems that arise from novel microbial associations, or increased susceptibility to native pests.

- Trees in botanic gardens, arboreta, large-scale plantations, and urban parks and yards can provide information on both existing native-to-native associations and new pest–host associations. Analyzing these plantings can be useful for studying host-shift events and novel pest–host associations. Again, all the taxa associated with the sentinel trees must be identified to ascertain whether they can become a threat to plants in the new ecosystem. Monitoring these planting have detected previously unknown plant–host associations (such as polyphagous shot hole borer and tree species in California and South Africa), and entirely unknown taxa. Pest surveillance in urban areas can also facilitate early detection, thereby strengthening the possibility of eradication.

Sentinel tree programs are limited by 1) small sample sizes; 2) immature trees; and 3) the fact that trees planted outside their native range might not be accurate surrogates for the same species in native conditions. Some of these issues can be reduced by establishing reciprocal international agreements among trading partners; the International Plant Sentinel Network helps to coordinate these collaborations.

Botanic gardens and arboreta have the advantage of containing adult trees; this is important because pest impacts can vary between sapling to mature trees. However, they probably contain only a few individuals per plant species, usually composed of narrow genetic base.

Large-scale plantations of exotic tree species, e.g., exotic commercial plantations, comprise large numbers of trees planted over large areas with varied environmental conditions, and they stand for longer times. Still, they commonly have a narrow genetic base that might not be representative of wild native plants. Also, only a few species are represented in commercial plantations.

Raffa et al. report that experience in commercial Eucalyptus plantations in Brazil alerted Australia to the threat from myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii). However, in an earlier blog I showed that Australia did not act quickly based on this knowledge.

- Laboratory assays using plant parts or seedlings

Laboratory tests artificially challenge seedlings, plant parts (e.g., leaves, branches, logs), or other forms of germplasm of potential hosts to determine their vulnerability. These tests are potentially powerful because they are amenable to experimental control, standardized challenge, and replication. They also avoid many of the logistical constraints of sentinel plantings. Finally, they can be performed relatively rapidly.

The key underlying assumption is that results can be extrapolated to predict injury to live, mature trees under natural conditions. The validity of this assumption depends on the degree to which exogenous biotic and abiotic stressors affect the outcomes. Raffa et al. report that environmental stressors tend to more strongly influence tree interactions with woodborers than folivores.

These assumption are more likely to be met by pathogens that infect shoots or young tissues, such as the myrtle rust pathogen Austropuccinia psidii, ash dieback pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, and the sudden oak death pathogen Phytophthora ramorum.

The host range of and relative susceptibilities to insects is usually tested on twigs bearing foliage for defoliators and sap suckers; bark disks, logs, or branches for bark beetles, ambrosia beetles, and wood borers. These methods do not work as well for bark beetle species that attack mature trees in which active induced responses and transport of resins through established ducts are critically important.

The major advantages of laboratory tests is that they readily incorporate both positive (known hosts) and negative (known nonhosts) controls, can provide a range of environmental conditions, can be performed relatively rapidly, are statistically replicable at relatively low costs, and can test multiple host species and genotypes simultaneously. The ability to statistically replicate a multiplicity of environmental combinations and species is particularly valuable for evaluating relationships under anticipated future climatic conditions.

However, there are several important limitations. In testing pathogens, environmental conditions required for infection are often unknown. Choice of non-conducive conditions might result in false negatives; choice of too-conducive conditions might result in exaggerating the likelihood of infection. Results of tests of insect pests can vary depending on whether the insects are allowed to choose among potential host plants. Other complications arise when the pest being evaluated requires alternate hosts. In addition, seedlings are not always good surrogates for mature trees – especially as regards pathogens and bark, wood-boring and root collar insects. Folivores are less affected by conditions. Plus, the costs can be significant since they involve maintaining a relatively large number of viable and virulent pathogen cultures, insects, and candidate trees in quarantine.

Finally, although lab assays are well suited for identifying new host associations, results might not be amenable to scaling up to predict a pest’s population-level performance in a new ecosystem. Scaling up is especially problematic for those insect species whose dynamics are strongly affected by trophic interactions.

SOURCE

Raffa, K.F., E.G. Brockerhoff, J-C Gregoire, R.C. Hamelin, A.M. Liebhold, A. Santini, R.C. Venette, and M.J. Wingfield. 2023. Approaches to Forecasting Damage by Invasive Forest P&P: A Cross-Assessment. BioScience Vol. 73 No. 2: 85–111 https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac108

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or