A guest blog by Michael Aucott. Mike is a retired research scientist of the NJ Department of Environmental Protection. He has also taught chemistry at the College of New Jersey. He is currently a member of the NJDEP Science Advisory Board Standing Committee on Climate and Atmospheric Sciences, and on the board of directors of the PA/NJ Chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation. If you wish to contact Mike, use the contact button on this website. You MUST include your email address; it is not recorded automatically.

Two major perturbations affect Earth and its living systems, climate change and habitat disruptions. Emerging data show that these are more closely related than previously realized; they are connected by carbon dioxide, CO2.

Climate change basics: the physics

Climate change concerns have focused on the alteration of weather and climate due to the increase in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide, CO2. The impact of CO2 on climate has been understood for at least 120 years. In 1896 the Nobel-Prize-winning Swedish chemist Svante Arhennius published calculations demonstrating that human emission of CO2, when combined with the positive feedback effects of water vapor, would warm the Earth (Arhennius, 1896). His equation, ΔF = α ln(C/C0), relates the change in climate “forcing” (the degree to which temperature change is forced) to the ratio of the concentration of CO2 currently in the atmosphere (C) to a previous concentration (C0). This equation is still in use today. Arhennius estimated that a doubling of CO2 would warm the Earth by about 4 degrees C. This estimate is not far off from current estimates based on much more elaborate calculations.

This warming impact is caused by the physics of CO2, water vapor, and other “greenhouse” gases. Infrared radiation causes the CO2, water, and other greenhouse gas molecules to vibrate, leading to the absorption of the energy carried by that radiation. Much of the solar energy coming from the sun is not in the infrared frequency range, so it passes through the atmosphere without being absorbed. However, when this energy is absorbed by the surfaces of the Earth and its biota, and is re-radiated as infrared radiation, it is then absorbed by greenhouse gases, warming the planet.

The amount of water vapor in the atmosphere is directly related to the atmosphere’s temperature: warm air holds more water vapor. Human activity hasn’t directly changed the concentration of water vapor in the atmosphere significantly. But by burning fossil fuels, humans have dramatically increased the atmospheric concentration of CO2 and in so doing, also indirectly increased the concentration of water vapor. Just as Arhennius predicted over 120 years ago, this increase in CO2 is warming the Earth.

Ramifications of this warming include increased heat episodes, the intensification of the hydrological cycle (greater frequency of both heavy precipitation events and of droughts), sea level rise due to the melting of land-based glaciers and the thermal expansion of ocean water, and, almost certainly, intensification of storms and an increase in extreme weather. These climate-warming- based perturbations have the potential to influence the functioning of Earth’s biota in many deleterious ways, and clearly can be associated with the many facets of habitat disruption.

Climate change amplifications: the chemistry

But there’s another aspect of CO2 that may be more important insofar as habitat disruption is concerned and that has been largely ignored: chemistry. CO2 is a trace gas as far as we humans and other animals are concerned, unnoticed by our bodies in normal life. But to plants it is a vital food. It is taken up by plants as an essential input to photosynthesis. In this chemical reaction, using the energy of sunlight, plants combine CO2 and water vapor to make oxygen and carbohydrates, represented with a generic formula of CH2O, according to the equation CO2 + H2O → CH2O + O2. Without this reaction, life as we know it would not exist.

The atmospheric concentration of CO2 has varied over time; some 50 million years ago it was considerably higher than today. However, for at least the last three million years, the concentration of CO2 has been in the range of 280 ppm. Over these millions of years biota have adapted to this concentration. But within the last 300 years, one ten thousandth of this period – a blink of an eye in the geological or evolutionary time scale – the concentration of CO2 has shot up to 420 ppm, a 50% increase, due to humanity’s burning of fossil fuels and forests.

Imagine what might happen to a person who had been on a tight dietary budget for most of his or her life but suddenly got access to 50% more carbohydrates, but no more protein or minerals? We could expect major changes in the metabolism of that person. This dramatic change is what has, in effect, happened to the whole of life on Earth. Our planet’s primary biota, plants, now suddenly have the opportunity to gorge on CO2. But their access to other important substances such as nitrogen has not changed. Evidence is accumulating that CO2 at its elevated level of 420 ppm is not, as has been proclaimed by some, a healthy influence but is instead throwing Earth’s ecosystem into disarray.

Much of the recent experimental evidence on the impacts of enriched atmospheric CO2 has been assembled by Lewis Ziska and presented in his new book, Greenhouse Planet: How Rising CO2 Changes Plants and Life as We Know It (Ziska, 2022; see full citation at the end of the blog). The findings documented in this book reveal a variety of impacts of elevated CO2. These impacts include stimulation of growth of invasive plants, decreases in the nutrient content of major crops, and changes in plants’ production of insecticidal, allergenic, and other compounds. The changing chemistry of plants may be contributing to a major die-off of insects and insect-eating animals including birds. Below are some details.

Habitat Disruptions: Stimulation of Invasive Plants

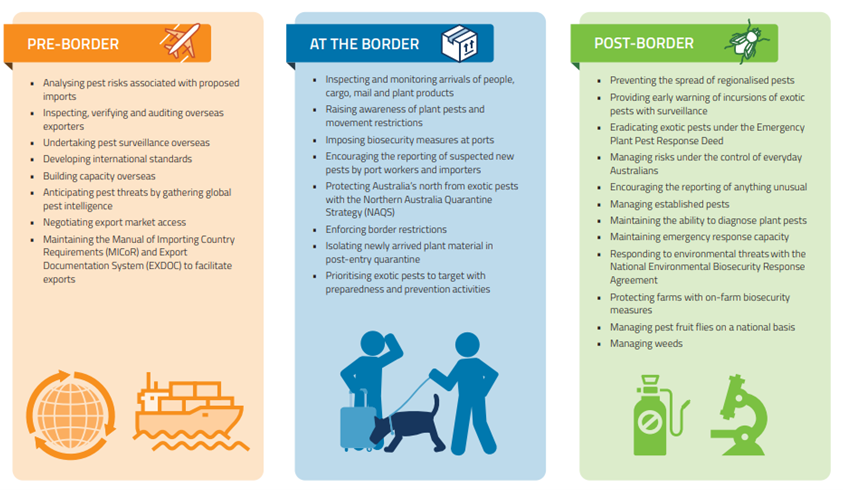

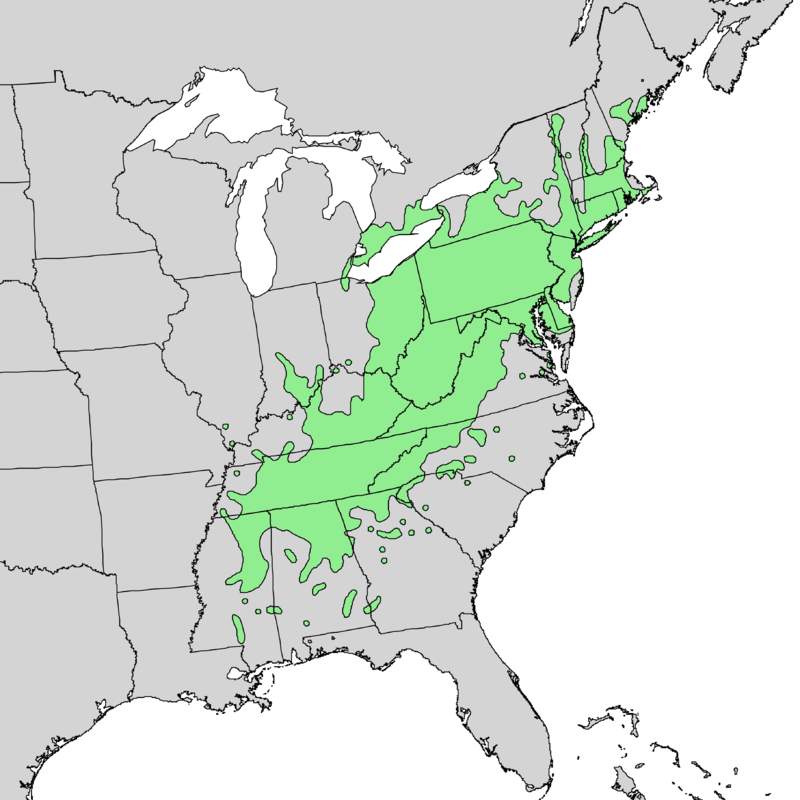

The generally accepted explanation for why some plants are invasive is that they have been introduced to new regions where their historic predators and parasites aren’t present. Without these drags on their growth, they have flourished. That some alien plants are not browsed by white-tailed deer contributes significantly to their invasiveness in Eastern North America. Other factors are clearly involved as well, including changes in the temperature regime and the availability of water and other resources such as nitrogen.

But elevated CO2 is also a factor. In recent years, techniques for measuring responses of organisms in situ under elevated CO2 conditions have been developed, making possible investigations of the impacts of CO2 concentrations that could exist in the future under otherwise relatively realistic conditions. What the actual atmospheric CO2 concentration will be in 2050 or 2100 is difficult to predict; it depends on what humanity does to control emissions. Various scenarios suggest that levels could exceed 500 ppm by 2050 and might exceed 1000 ppm by 2100 (Tollefson, 2020).

One study found that the invasive weed Canada thistle, Cirsium arvense, responds more strongly to elevated CO2 than soybean, a crop that it often plagues. In a high CO2 environment, this weed’s root system grows strongly enough to make it significantly more resistant to herbicides (Ziska, et al., 2004) (Ziska, 2010). The highly invasive and dangerously flammable cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), nicknamed “grassoline” by the U.S. Forest Service because of its propensity to intensify wildfires, also responds strongly to elevated CO2 (Ziska, et al., 2005). Also found to be boosted by enriched CO2 is yellow star-thistle (Centaurea solstitialis), considered one of California’s worst weeds. In one study (Dukes, et al., 2011) this plant grew 600% larger in elevated CO2 relative to ambient, while native plants responded much less strongly or not at all. Japanese honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica, which plagues many areas in the U.S., was found to increase in biomass by 135% at a CO2 concentration of 675 ppm while a similar native plant, coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) increased by only 40% (Sasek & Strain, 1991). In a field study also involving Japanese honeysuckle (Belote, et al., 2004), researchers found that its above ground net production (ANPP) approximately tripled under enriched CO2 while other plants in the trial showed showed lesser increases or actual decreases.

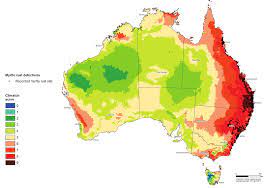

Other plants have been found to be selectively encouraged by enriched CO2 including cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus), invasive in the Pacific Northwest U.S. and the U.K., (Hattenschwiler & Korner, 2002); dalmation toadflax (Linaria dalmatica), invasive in much of North America (Blumenthal, et al., 2013); honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) , invasive in Australia and parts of Africa (Polley, et al., 1996); and kudzu (Pueraria lobata), which afflicts the Southeast U.S. (Sasek & Strain, 1988). Three plants invasive in China or Southeast Asia, American rope (Mikania micrantha), Creeping oxeye (Wedelia trilobata), and a morning glory species (Ipomoea cairica), were found to produce 70.3% greater biomass when grown at a CO2 concentration of 700 ppm while three corresponding indigenous plants Paederia scandens, Wedelia chinensis and Ipomoea pescaprae, produced only 30.5% more biomass (Song, et al., 2009).

The list goes on of studies showing increased growth of some plants under enriched CO2 conditions. As more in situ investigations are undertaken, it seems likely it will become clearer that today’s enriched level of CO2 is helping some plants to become invasive.

Complexities and contradictory findings exist however. Not all plants are stimulated by enriched CO2. An important difference in the response to higher levels of CO2 is whether a plant has a C3 or a C4 photosynthetic mechanism. C4 plants contain a biochemical pump that concentrates CO2, making them more adapted to low CO2 conditions (Hager, et al., 2016). At current levels of CO2, such plants’ need for CO2 is easily met. C3 plants do not have this CO2 concentrating ability, and so higher levels boost their growth. In a broad meta-analysis of literature, the average response to elevated CO2 of 365 C3 plant species and 37 C4 plant species was noted; the response was significantly increased in C3 species but was unchanged in C4 species (Robinson, et al. 2012). One striking example of such a difference was observed in the field study noted above (Belote, et al., 2004), wherein researchers found that Japanese honeysuckle (a C3 plant) was significantly encouraged by elevated CO2 relative to other plants at the same locale. The same study found that another aggressive invader, Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), a C4 plant, was unaffected or even slightly inhibited relative to competing plants’ growth by elevated CO2.

Habitat Disruptions: Changing of Plants’ C/N Ratio and Nutrient Content

One finding is widespread; most plants studied under enriched CO2 regimes show an increase in biomass and evince a higher ratio of carbon to nitrogen (C/N ratio) in their tissues and an overall decline in nitrogen concentrations than when grown under ambient conditions. Since nitrogen is a key component of protein, this change can be expected to lead to lowered protein content of critical food crops. Some impacts of this change are already well underway because of today’s elevated CO2 concentration. Changes since 1850 in the C/N ratio and in the estimated protein content of an important plant product, pollen, were discovered in a striking study by Lewis Ziska and colleagues (Ziska, et al., 2016). Using archived museum samples, these researchers determined the nitrogen content of pollen of Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod) going back to the 1850s. They estimated that the protein content of goldenrod pollen, a vital nutrient for North American bees, has declined in inverse proportion to the rise in atmospheric CO2, dropping from a concentration of approximately 18% in the mid-1800s to approximately 12% today. They pointed out that it is possible that bees are now unable to provide sufficient protein and other nutrients to larvae, and that one of the main reasons for bee declines is malnutrition caused by enriched atmospheric CO2. Other studies also indicate that elevated CO2 could cause lower nitrogen concentrations in plants and lead to less proteinaceous plant parts, including pollen, being available to plant-feeding insects (Hall, et al., 2005; Knepp, et al., 2007).

The changing C/N ratio is almost certainly already affecting the human food supply. As documented in an extensive review of published findings (Soares, et al., 2019), elevated CO2 has a considerable impact on the accumulation of minerals and protein in plants, with many plant species showing declines in both quality and quantity of key nutrients. These changes have worrisome implications for human nutrition and may already be responsible for increasing incidences of dietary deficiency in some areas. Lewis Ziska discusses the likely impact of rising CO2 on the future human food supply in his recent post. A number of studies showing declines in protein and also other nutrients such as zinc in food crops important to humanity are also described in Ziska’s new book, Greenhouse Planet, noted above.

Habitat Disruptions: Other Changes in Plant Chemistry

Other changes in plants besides nutritional content may be driven by enriched CO2. Plants produce a variety of secondary metabolites. Most plants use the C3 mechanism; with 50% more available of a key input, some changes in these plants’ production of such chemicals can be expected. Some changes have been observed. Mohan et al. (2006) report that enriched CO2 in an intact forest system increased water use efficiency, growth, and population biomass of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) and that high-CO2 plants also produced a more toxic form of the allergenic compound urushiol.

Many of the phytochemicals plants produce function as defenses against insect predation, and changes in such production have been found to impact herbivore feeding. For example, Landosky and Karowe (2014) suggest that specialist herbivores may have to contend with more effective chemical defenses by plants under elevated CO2. Hall, et al. (2005), in a study involving several oak and one legume species in a scrub oak ecosystem in Florida (see photo above), found that 700 ppm CO2 levels led to decreased damage to plants by four of six insect groups investigated. They did not see increases in plants’ production of carbon-based secondary metabolites, including total phenolic compounds, condensed tannins, hydrolyzable tannins, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin however. They concluded that the primary driver of decreased insect predation under elevated CO2 was lower overall plant nitrogen levels. They stated that the decline of nitrogen levels in foliage under elevated CO2 indicated lower foliar quality and hypothesized that the reductions in insect feeding stemmed from the combined effects of nutrient limitation and increases in parasitism and predation on the nutrient-constrained insects. They further stated that although insects try to compensate for lower nutrient content of leaves by eating more, they did not see an increased portion of damaged leaves in their study. These researchers did not report measurements of terpenoid compounds however, which are reported to represent the largest class of secondary metabolites (Wikipedia, 2022). In another study (Hall, et al., 2005a) found that concentrations of condensed tannins were higher in oak leaf litter under elevated CO2, which suggests that enhanced production of insecticidal compounds or other changes to plant tissues could affect not only insects that consume living plant tissue, but also detritivores.

Robinson et al. (2012) also investigated plants’ production of secondary metabolites in their literature review. Looking at all plant groups, they found that under elevated CO2 the production of nitrogen-based secondary metabolites (e.g., alkaloids, cyanogenic glycosides, and glucosinolates) decreased by 16% while the carbon-based secondary metabolites total phenolics, condensed tannins, and flavonoids increased by 19%, 22%, and 27% respectively. Another carbon-based metabolite, terpenoids, declined by 13%. They further divided plants into grasses, shrubs, herbs/forbs, and trees and found differing responses to elevated CO2. Trees, for example, showed increased production of total glycosides and total phenolics, little change in production of total flavonoids, and a decline in the production of total terpenes. Like Hall et al., (2005), Robinson et al. found a strong and significant decrease in nitrogen concentrations under elevated CO2 for C3 plants. A decrease did not show up for C4 plants.

In addition to chemical defenses, plants have physical characteristics such as surface waxes, trichomes, secretory canals, and tissue toughness-enhancing substances such as lignin. All of these features can reduce the edibility of plants for arthropod herbivores. Robinson et al. (2012) found consistent responses to these characteristics under elevated CO2; leaf toughness and specific leaf weight increased by 11% and 18%, respectively, while specific leaf area did not show a significant change. They concluded that there is an increase in general “toughness” of leaves under elevated CO2. As did Hall et al., (2005), Robinson et al. concluded that elevated CO2 will induce changes in plant chemistry, physiology, and morphology that are likely to impact the nutritional quality of host plants for insect herbivores.

Habitat Disruptions: Changes in Plant Chemistry and Insect Decline

Numerous studies have documented a recent and dramatic decline in insect populations and discussed the probable cascading impacts of such declines through the food chain, affecting spiders, lizards, birds, and other organisms (Samways, et al., 2020; Cardoso, et al., 2020; Sánchez-Bayoa & Wyckhuys, 2019; Tallamy & Shriver, 2021). It has been argued that the main drivers of insect species declines are habitat loss and conversion to intensive agriculture and urbanization; pollution, mainly by synthetic pesticides and fertilizers; biological factors, including pathogens and introduced species; and climate change.

But a puzzling aspect is that some insect declines have been observed in nature preserves (Vogel, 2017) that presumably are not greatly affected by most of the above drivers. One example is a study spanning 27 years that found a 76% decline in flying insect biomass at several of Germany’s protected areas subject to rather low levels of human disturbance (Hallmann et al., 2017). Another study in rainforests of Puerto Rico, apparently not subject to influences such as light pollution, habitat loss, pesticides, or agriculture, reported biomass losses between 98% and 78% for ground-foraging and canopy-dwelling arthropods over a 36-year period, (Lister and Garcia, 2018). This leaves climate change as the likely culprit. But although the varied impacts of climate change, including heat episodes, drought, and other episodes of extreme weather could impact insect populations in remote as well as populated areas, the trends observed appear to far exceed the magnitude of such climate-related disturbances over the last several decades.

Another puzzling aspect is that not all insect orders or feeding guilds seem to be equally affected. Sanchez-Bayoa & Wychuys (2019) whose article reports on a review of 73 historical reports, state that Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera and dung beetles (Coleoptera) appear to be the taxa most affected in terrestrial environments. Robinson et al. (2012) found that phloem feeders such as Homoptera respond positively to elevated CO2 while foliage feeders/Lepidoptera respond negatively. Lepidoptera were among the most impacted; relative growth rate, fecundity, and abundance all declined under high CO2 conditions, while relative consumption rate, total consumption, and development time all increased.

Most Lepidoptera are herbivorous, feeding in their larval stage, caterpillars, on plants. Caterpillars are key components of the terrestrial ecology; in most forests of the world, caterpillars consume more living leaves than all other animals combined (Janzen, 1988). Insect herbivores such as caterpillars are near the hub of most terrestrial food webs, comprising essential food for insect predators and parasitoids, spiders, amphibians, lizards, rodents, bats, birds, and even higher predators such as foxes and bears (Burghardt et al., 2010). At least 310 North American bird species are known to feed extensively on caterpillars, and the majority of terrestrial birds rely on insects during reproduction and other nutrient-limited periods in the annual cycle (Narango, Tallamy & Marra, 2018). Caterpillars and moths are the largest component of nestling diets in hundreds of species of migrant bird species (Tallamy & Shriver, 2021); they are among the “little things that run the world” (Wilson, 1987).

Habitat Disruptions and Climate Change: Connected by CO2

The apparently heightened rate of decline of insect herbivores such as caterpillars compared to some other insects, and the findings that many declines have been observed in areas relatively unimpacted by direct human influences such as light pollution, pesticides, and land-use change, point to the likelihood of a broad, perhaps ubiquitous, cause. Climate change is such a broad cause. Even broader and more ubiquitous is the main driver of climate change, CO2. Every plant in the world is constantly bathed in an enriched concentration of this gas. A conclusion seems likely: CO2 is not only causing global warming and climate change but is also affecting life on this planet in ways that, while still poorly understood, are already reducing the nutritive value of food crops, may be a significant cause of the spread of invasive plants, and may be the main driver of insect declines and the cascading impacts of such declines on insect-eating animals such as birds.

What to do?

To mitigate climate change and, as argued here, to mitigate habitat disruption, the steady rise in the atmosphere’s burden of CO2 must be halted, and then steps must be taken to lower the current concentration to a healthier level. These are not hopeless tasks. Although what has been a relentless rise in CO2 emissions at the global level continues, increases have slowed and even stopped in some parts of the world. Accelerating the development of low- and zero-carbon energy sources and encouraging energy conservation, as will be done through the U.S.’s Inflation Reduction Act, will further this progress.

More will be needed. Putting a significant and steadily increasing price on the carbon in fossil fuels is arguably the most important next step. Fossil fuels enjoy a free ride. The byproduct of their combustion, CO2, is dumped with little or no restrictions into the world’s atmosphere. A price on carbon would end this inequity. There are ways this could be done in a revenue-neutral (“fee and rebate”) manner that would avoid harm to economies and those with low- and moderate-incomes. A major step forward in pricing carbon by the European Union, a carbon border adjustment mechanism, is close to implementation. For more on this and other developments in cutting CO2 emissions, see the analyses and insights of the Carbon Tax Center and learn more about actions you can take to influence governments with Citizens’ Climate Lobby.

Not discussed here, but another stark example of habitat disruption is the increasing acidification of the world’s oceans caused by the dissolution of atmospheric CO2 in the waters. The ocean’s average pH has dropped from 8.2 to 8.1 within the last 200 years. Because pH is a logarithmic scale, this represents an increase in hydrogen ion concentration of over 25%, a change that is already threatening some marine creatures. More on this is available from many sources; e.g., Kolbert (2014).

References

Arhennius, Svante, 1896, On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature on the Ground, Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 41, 237-276.

Belote, R., J. Weltzin, and R. Norby, 2004, Response of an Understory Plant Community to Elevated [CO2] Depends on Differential Responses of Dominant Invasive Species and Is Mediated by Soil Water Availability, New Phytologist 161, 827-835.

Blumenthal, D., V. Resco, J. Morgan, D. Williams, D. LeCain, E. Hardy, E. Pendall, and E. Bladyka, 2013, Invasive Forb Benefits from Water Savings by Native Plants and Carbon Fertilization Under Elevated CO2 and Warming, New Phytologist 200, 1156-1165.

Burghardt, Karin T., D. W. Tallamy, C. Philips, and K. Shropshire, 2010, Non-native plants reduce abundance, richness, and host specialization in lepidopteran communities, Ecosphere 1: 1-22.

Cardoso, P., et al. 2020, Scientists’ warning to humanity on insect extinctions, Biological Conservation 242, 108426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108426

Dukes, J., N. Chiariello, S. Loarie, and C. Field, 2011, Strong Response of an Invasive Plant Species (Centaurea solstitialis L.) to Global Environmental Changes, Ecological Applications 21, 1887-1894.

Hall, M., P. Stiling, B. Hungate, B. Drake, and M. Hunter, 2005a, Effects of elevated CO2 and herbivore damage on litter quality in a scrub oak ecosystem, Journal of Chemical Ecology, 31, 2343-2356.

Hall, M., P. Stiling, D. Moon, B. Drake, and M. Hunter, 2005, Effects of elevated CO2 of foliar quality and herbivore damage in a scrub oak ecosystem. Journal of Chemical Ecology 31, 267-286.

Hallmann, C.A., Sorg, M., Jongejans, E., Siepel, H., Hofland, N., Schwan, H., Stenmans, W., Müller, A., Sumser, H., Hörren, T., Goulson, D., de Kroon, H., 2017, More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One 12, e0185809.

Hattenschwiler, S. and C. Korner, 2003, Does Elevated CO2 Facilitate Naturalization of the Non-indegenous Prunus laurocerasus in Swiss Temperate Forests?, Functional Ecology 17, 778-785.

Janzen, Daniel H., 1988, Ecological Characterization of a Costa Rican Dry Forest Caterpillar Fauna, Biotropica, 20, 120-135.

Knepp, R., J. Hamilton, A. Zangeri, M. Berenbaum, and E. Delucia, 2007, Foliage of oaks grown under elevated CO2 reduces performance of Antherae Polyphemus (Lepidoptera: Saturnidae), Environmental Entomology 36, 609-617.

Kolbert, E., 2014, The Sixth Extinction, Henry Holt & Co., NY

Landosky, J., and D. Karowe, 2014, Will chemical defenses become more effective against specialist herbivores under elevated CO2? Global Change Biology, 20, 3159–3176.

Lister, B., and A. Garcia, 2018, Climate-driven declines in arthropod abundance restructure a rainforest food web, PNAS 115, E10397–E10406

Mohan, J., L. Ziska, W. Schlesinger, R. Thomas, R. Sicher, K. George, and J. Clark, 2006, Biomass and toxicity responses of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) to elevated atmospheric CO2. PNAS 103, 9086-9089.

Narango, D., D. Tallamy, and P. Marra, 2018, Nonnative plants reduce population growth of an insectivorous bird, PNAS 115: 11549–11554.

Polley, H., H. Johnson, H. Mayeux, C. Tischler, and D. Brown, 1996, Carbon Dioxide Enrichment Improves Growth, Water Relations, and Survival of Droughted Honey Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) Seedlings, Tree Physiology, 16, 817-823.

Robinson, E., G. Ryan, and J. Newman, 2012, A meta-analytical review of the effects of elevated CO2 on plant-arthropod interactions highlights the importance of interacting environmental and biological variables, New Phytologist 194, 321-336.

Samways, M., et al., 2020, Solutions for humanity on how to conserve insects, Biological Conservation 242, 108427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108427

Sánchez-Bayoa, F. and K. Wyckhuys, 2019, Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers, Biological Conservation 232, 8-27.

Sasek, T. and B. Strain, 1988, Effects of Carbon Dioxide Enrichment on the Growth and Morphology of Kudzu (Pueraria lobata), Weed Science 36, 28 – 36, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043174500074415

Sasek, T. and B. Strain, 1991, Effects of CO2 Enrichment on the Growth and Morphology of a Native and Introduced Honeysuckle Vine, American Journal of Botany 78, 69-75.

Soares, J., C. Santos, S Carvalho, M Pintado, and M. Vasconceios, 2019, Preserving the nutritional quality of crop plants under a changing climate: importance and strategies. Plant and Soil 443, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04229-0

Song, L., J. Wu, C. Li, F. Li, S. Peng, and B. Chen, 2009, Different responses of invasive and native species to elevated CO2 concentration, Acta Oecologica 35, 128-135.

Tallamy, D. and W.G. Shriver, 2021, Are declines in insects and insectivorous birds related? Ornithological Applications 123: 1–8, DOI: 10.1093/ornithapp/duaa059

Tollefson, J., 2020, How hot will Earth get by 2100? Nature News Feature, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01125-x accessed 12/15/2022

Vogel, G., 2017, Where Have All the Insects Gone? Surveys in German nature preserves point to a dramatic decline in insect biomass. Key members of ecosystems may be slipping away, Science 356, 376-379.

Wikipedia, 2022, Terpenoid, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terpenoid accessed 12/16/22.

Wilson, Edward O., 1987, The Little Things That Run the World (The Importance and Conservation of Invertebrates), Conservation Biology, 1, 344-346.

Ziska, L., 2010, Elevated Carbon Dioxide Alters Chemical Management of Canada Thistle in No-till Soybean, Field Crops Research 119, 299-303.

Ziska, L., Shaun Falukner, and John Lydon, 2004, Changes in biomass and root: Shoot Ratio of Field-grown Canada Thistle (Cirsium arvense), a Noxious, Invasive Wed, with Elevated CO2: Implications for Control with Glyphosate, Weed Science 52, 584-588.

Ziska, L.H., J.S. Pettis, J. Edwards, J.E. Hancock, M.B. Tomecek, A. Clark, J.S. Dukes, I. Loladze, and H.W. Polley, 2016, Rising atmospheric CO2 is reducing the protein concentration of a floral pollen source essential for North American bees, Proc. R. Soc. B, 283, 20160414, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0414

Ziska, Lewis, 2022, Greenhouse Planet: How Rising CO2 Changes Plants and Life as We Know It, Columbia University Press, NY.