American beech; FT Campbell

American beech; FT Campbell

I recently attended USDA’s annual Interagency Research Forum on Invasive Species in Annapolis, MD, and have good and bad news to report about forest pests – mostly about insects but also a little on weeds.

Bad News

New pest: The European leaf-mining weevil is killing American beech in Nova Scotia. Jon Sweeney of Natural Resources Canada thinks it could spread throughout the tree species’ range. (I alerted you to another new pest of beech – beech leaf disease – at the beginning of December. Beech is already hard-hit by beech bark disease.)

New information added in June: according to Meurisse et al. (2018), the weevil overwinters under the bark of beech and trees that are not hosts, so it can be transported by movement of firewood and other forms of unprocessed logs and branches. [Meurisse, N. D. Rassaati, B.P. Hurley, E.G. Brockerhoff, R.A. Haack. 2018. Common Pathways by which NIS forest insects move internationally and domestically. Journal of Pest Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-0990-0]

Other bad news concerns the spread of already-established pests:

- Hemlock woolly adelgid has been detected in Nova Scotia – where it has probably been present for years.

- Emerald ash borer has been detected in Winnipeg, Manitoba – home to an estimated 350,000 ash trees. Winnipeg is 1,300 km (870 miles) from Saulte Ste. Marie, the closest Canadian outbreak. The closest U.S. outbreak is in Duluth, Minnesota — 378 miles.

- Despite strenuous efforts by Pennsylvania (supported, but not adequately, by APHIS), (see my blog from last February ), spotted lanternfly has been detected in Delaware, New York, and Virginia. A map showing locations of apple orchards in the Winchester, Virginia area is available here.

- There is continued lack of clarity about biology and impact of velvet longhorned beetle (see my blog from last February.) The Utah population appears to be growing. APHIS is funding efforts to develop trapping tools to monitor the species.

- Alerted at the Forum, I investigated a disease on oak trees caused by the pathogen Diplodia corticola. Already recorded in Florida, California, Massachusetts and Maine, last year the disease was also detected in West Virginia. Forest pathologists Danielle Martin and Matt Kasson don’t expect this disease to cause widespread mortality. However, they do expect it to weaken oaks and increase their vulnerability to other threats.

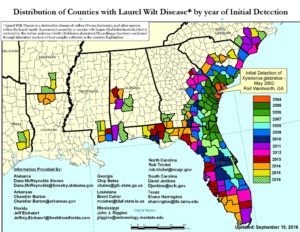

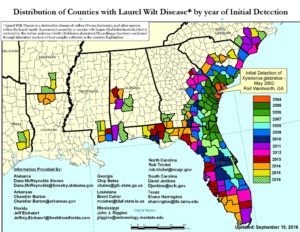

spread of laurel wilt disease

spread of laurel wilt disease

Laurel wilt disease is one of the worst of the established non-native pests. Two speakers at the Forum described its ecological impacts.

Dr. John Riggins of the University of Mississippi reported that 24 native herbivorous insects are highly dependent on plants vulnerable to the laurel wilt insect-pathogen complex. One of these, the Palamedes swallowtail butterfly (Papilio palamedes) has suffered a three-fold to seven-fold decline in populations at study sites after the death of redbay caused by laurel wilt.

Dr. Frank Koch of the USDA Forest Service expects that the disease will spread throughout most of the range of another host, sassafras. (See a map of the plant’s range). With the climate changing, the insect is unlikely to suffer winter cold mortality in the heart of the tree’s range in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia.

Apparently many birds depend on spicebush, a shrub in the Lauraceae family, but there is no easily available data on any changes to its distribution or health.

Good News

Other speakers at the Forum provided encouraging information.

Scientists described progress on breeding American elm trees resistant to or tolerant of the introduced Dutch elm disease (DED). USFS scientists led by James Slavicek and Kathleen Knight are trying to improve the genetic diversity and form of disease-tolerant American elms and to develop strategies for restoring them to the forest.

More than 70 seedlings planted in an orchard are being inoculated with the DED pathogen to test the trees’ tolerance. The project continues to collect seeds or cuttings from apparently resistant or tolerant trees. If you are aware of a large surviving elm in a natural setting (not urban planting), please contact the program via its website.

The project is also experimenting with methods for restoring trees in the forest. In one such experiment, elms, sycamores, and pin oaks have been planted at sites in Ohio where openings had been created by the death of ash attacked by emerald ash borer. Survival of the elm seedlings has been promising.

Also, there is cause to be optimistic re:

- Walnut / thousand cankers disease

In the East, walnut trees appear to recover from thousand cankers disease. One factor, according to Matt Ginzel of Purdue University, is that the thousand canker disease fungus, Geosmithia morbida, is a weak annual canker that would not cause branch or tree mortality in the absence of mass attack by the walnut twig beetle. Another factor is the greater reliability of precipitation in the East. Dr. Ginzel is now studying whether mass attack by the beetle is sufficient – alone – to kill walnut trees.

- b) Sirex noctilio

In Ontario, Laurel Haavik, U.S. Forest Service, finds both low impacts (so far) and evidence of resistance in some pine trees.

Also, scientists are making progress in developing tools for detecting and combatting highly damaging pests.

- Richard Stouthammer of U.C. Riverside has detected an effective chemical attractant for use in monitoring polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers. He is testing other pheromones that could improve the attractant’s efficacy. He has also detected some chemicals that apparently repel the beetles. His colleague, pathologist Akiv Eskalen, is testing endophytes that attack the beetles’ Fusarium fungus.

- Several scientists are identifying improved techniques for surveillance trapping for wood-boring beetles. These include Jon Sweeney of Natural Resources Canada and Jeremy Allison of the Great Lakes Forestry Centre.

Progress has also been made in biocontrol programs targetting non-native forest pests.

- Winter moth

Joseph Elkington of the University of Massachusetts reports success following 12 years of releases of the Cyzenis moth – a classical biocontrol agent that co-evolved with the winter moth in Europe. The picture is complex since the moths are eaten by native species of insects and small mammals and parasitized by a native wasp. However, native predators didn’t control the winter moth when it first entered Massachusetts.

2) Emerald ash borer

Jian Duan of the Agriculture Research Service reported that biocontrol agents targeting the are having an impact on beetle densities in Michigan, where several parasitoids were released in 2007 to 2010. The larval parasitoid Tetrasrticus planipennisi appears to be having the greatest impact. A survey of ash saplings at these sites in 2015 found that more than 70% lacked fresh EAB galleries. In other trees, larval density was very low – a level of attack that Duan thinks the trees can survive.

However, Tetrasrticus has a short ovipositor so it is unlikely to be able to reach EAB larvae in larger trees with thicker bark. Furthermore, most of the biocontrol agents were collected at about 40o North latitude. It is unclear whether they will be as successful in controlling EAB outbreaks farther South.

Consequently, Duan noted the need to expand the rearing and release of a second, larger braconid wasp Spathius galinae, continue exploration in the southern and western edges of the EAB native range for new parasitoids; and continue work to determine the role of the egg parasitoids.

A brochure describing the U.S. EAB biocontrol program is available here

Canada began its EAB biocontrol program in 2013, using parasitoids raised by USDA APHIS. While evaluating the efficacy of these releases, Canada is also testing whether biocontrol can protect street trees.

3) Hemlock woolly adelgid

Scientists have been searching for a suite of biocontrol agents to control HWA for 25 years. Scientists believe that they need two sets of agents – those that will feed on the adelgid during spring/summer and those that will feed on HWA during winter/spring.

The first agent, Sasajiscymnus tsugae, was released in large numbers beginning in 1995. It is easy to rear. However, there are questions regarding its establishment and impact.

Laricobius nigrinus – a winter/spring feeder from the Pacific Northwest – was released beginning in 2003. It is widely established, especially in warmer areas. A related beetle, L. osakensis, was discovered in a part of Japan where eastern North American populations of HWA originated. Releases started in 2012. Scientists are hopeful that this beetle will prove more effective than some of the other biocontrol agents.

Winter cold snaps in the Northeast have killed HWA. While HWA populations often rebound quickly, predatory insects might suffer longer-term mortality. This risk intensifies the importance of finding agents that attack HWA during the spring or summer. Two new agents – the silver flies Leucopis artenticollis and L. piniperda – may be able to fill this niche. Both are from the Pacific Northwest. Initial releases have established populations.

4) USDA scientists are at earlier stages of actively seeking and testing possible biocontrol agents targetting Asian longhorned beetle and spotted lanternfly.

5) Invasive Plant Management

A study in New York City shows that invasive plant removal can have lasting effects. Lea Johnson of the University of Maryland studied vegetation dynamics in urban forest patches in New York City. Her publications are available here.

In the 1980s New York undertook large scale restoration of its parks, including removal of invasive plants – especially multiflora rose, porcelainberry (Ampelopsis) and oriental bittersweet (Celastris). The goal was to establish self-sustaining forest with regeneration of native species. In 2006, Dr. Johnson was asked to evaluate the parks’ vegetation. She compared restored sites and similar sites without restoration.

I find it promising that Dr. Johnson found persistent differences in forest structure and composition as much as 15 or 20 years after restoration was undertaken. Treated sites had significantly lower invasive species abundance, a more complex forest structure, and greater native tree recruitment.

Still, shade intolerant species were abundant on all sites. The native shade tolerant species that had been planted did not do as well because gaps in the canopy persist.

CONCLUSIONS

As always, the annual Interagency Research Forum on Invasive Species provides an excellent opportunity to get an overview of non-native pest threats to America’s forests and the ever-wider range of scientists’ efforts to combat those threats. Presenters from universities as well as USDA, Canadian, and state agencies describe the status of host tree and pest species, advance promising technologies for detection, monitoring and control, and – increasingly – strategies for predicting potential pests’ likely impact. The networking opportunities are unparalleled.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

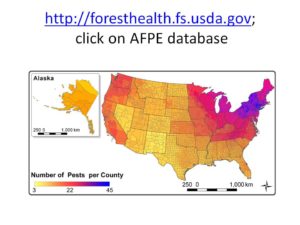

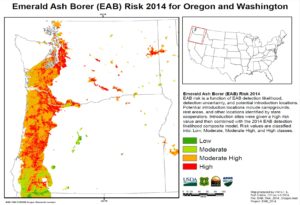

EAB risk to Oregon & Washington

EAB risk to Oregon & Washington