Since July 2015 I have posted nearly 50 blogs about non-native insects introduced via movement of solid wood packaging material (SWPM). Why? Because SWPM is one of two most important pathways by numbers introduced & by impact of the species introduced. (The other pathway is P4P.) To read those earlier blogs, scroll below “archives” to “categories”, choose “wood packaging”.

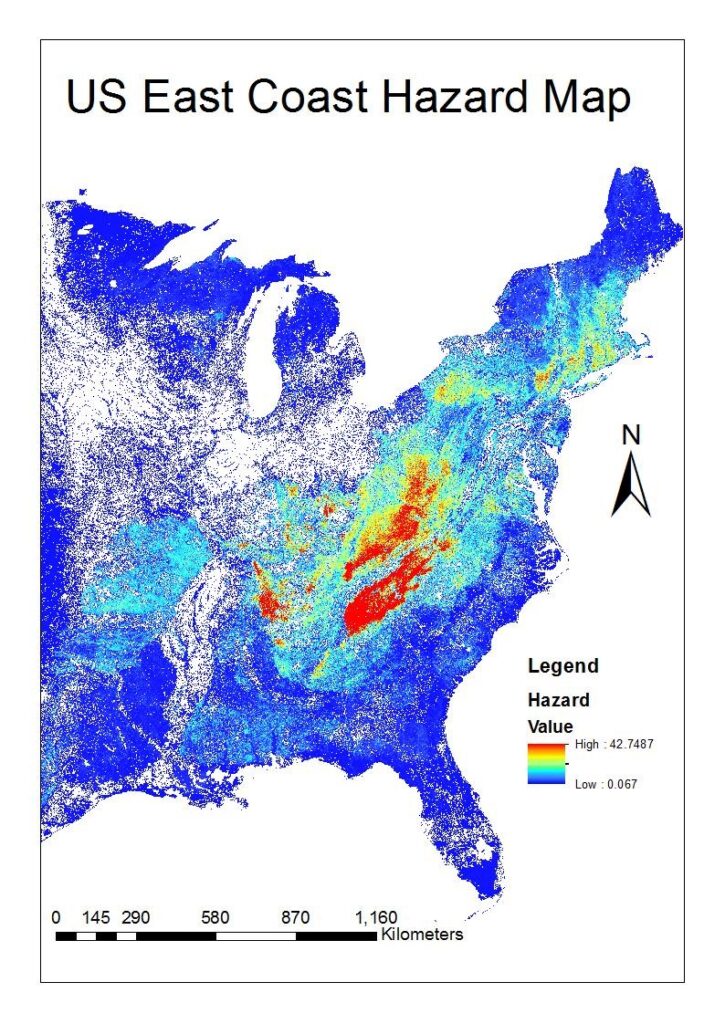

Examples of insects introduced via the wood packaging pathway include Asian longhorned beetle, emerald ash borer, redbay ambrosia beetle, Mediterranean oak borer, and possibly, three species of invasive shot hole borers.

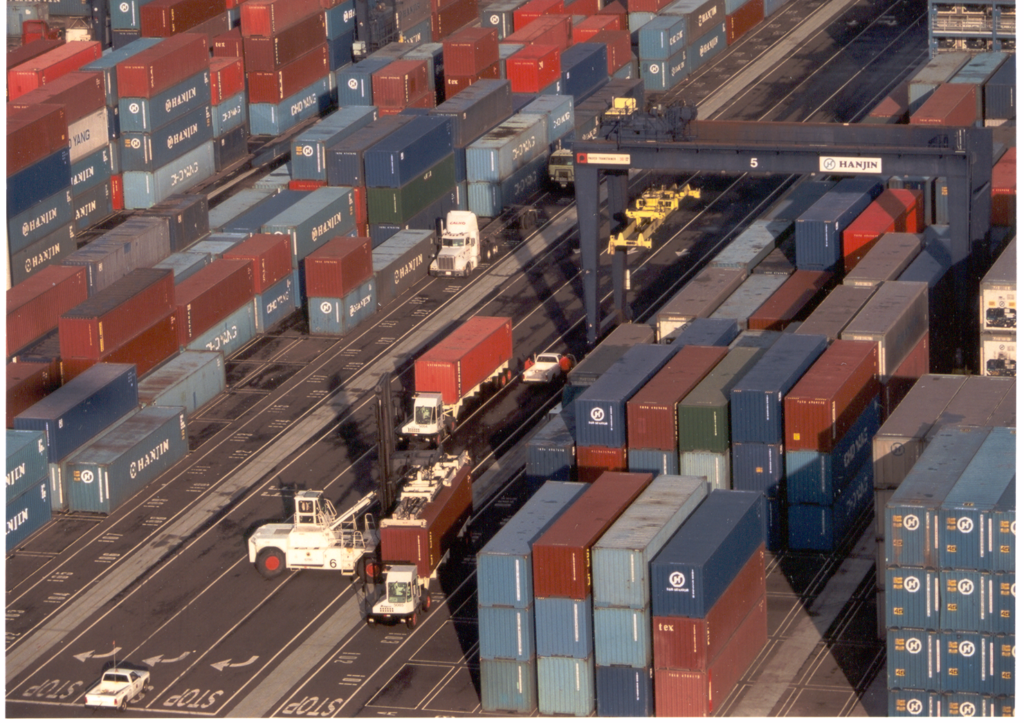

As I have reported in the earlier blogs and in my “Fading Forests” reports (links at the end of this blog), in 2002, the parties to the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) adopted an international “standard” to guide countries’ programs intended to reduce the presence of damaging insects in the wood packaging: International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) #15). The U.S. and Canada adopted the standard through a phase-in process culminating in 2006. [For a discussion of the phase-in periods and process, read either of the studies by Haack et al. cited at the end of this blog.] In other words, the U.S. and Canada have implemented ISPM#15 for almost 20 years. China specifically has been subject to requirements that it treat its SWPM even longer – since December, 1998, i.e., more than 25 years.

Unfortunately, ISPM#15 is not intended to prevent pest introductions. As stated in Greenwood et al 2023, “Prior to 2009, the goal of compliance with ISPM 15 was to render the risk of wood-borne pests “practically eliminated,” in 2009 the standard was amended to “significantly reduced”.

Despite almost universal adoption of the standard by countries engaged in international trade, insects have continued to be present in wood packaging. A very high proportion of these infested shipments — 87% – 95% — of the SWPM found by U.S. officials bears the ISPM#15 stamp – that is, is apparently compliant. (See my blogs by clicking on the “Category” “wood packaging” listed below the “Archives”.) The same proportion was found in a narrower study in Europe (Eyre et al. 2018). All the post-2006 examples of infested wood analyzed by Haack et al. (2022) (see below) carry the stamp. I conclude that the ISPM#15 mark has failed in its purpose: to reliably indicate that SWPM accompanying imports has been treated so as to minimize the likelihood that an insect pest will be present.

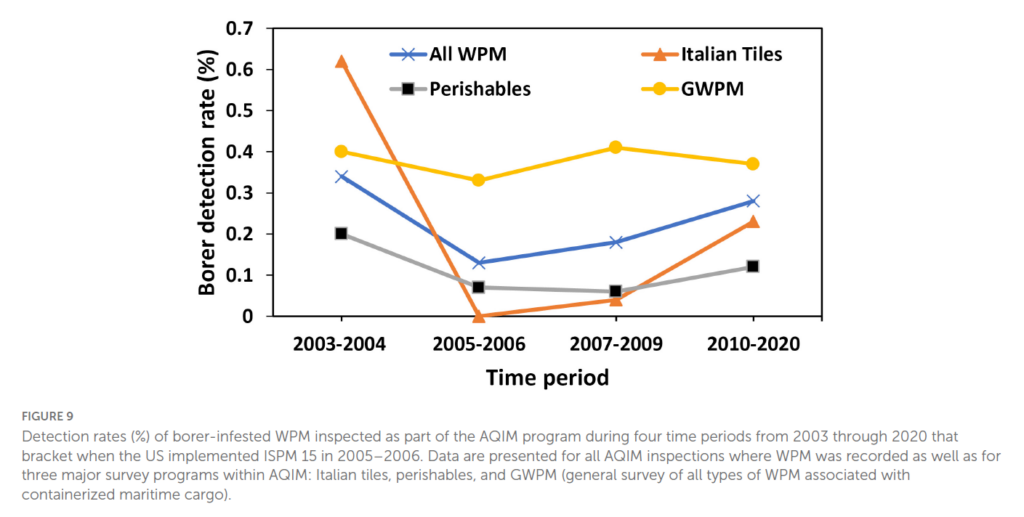

Dr. Robert Haack, retired USFS entomologist, has twice tried to estimate the “approach rate” of insects in SWPM entering the United States (both studies are cited at the end of this blog). A study published in 2014 that relied on data from 2009 found that U.S. implementation of ISPM#15 was associated with a reduction in the SWPM infestation rate reported of 36–52%. The authors estimated the infestation rate to be 0.1% (1/10th of 1%, or 1 consignment out of a thousand). (See Haack et al. 2014; citation at the end of this blog.)

In their second study, published in 2022, Haack and colleagues found a 61% decrease in rates of borer detection in wood packaging when comparing numbers of wood borer detections in 2003 – before the U.S. implemented ISPM#15 – to those in 2020. Specifically, detections dropped from 0.34% in 2003 to 0.21% in 2020. This decrease occurred despite the volume of U.S. imports rising 68% between 2003 and 2020. (My blogs document a further increase in import volumes over the years since 2020.) In addition, the number of countries from which the SWPM originated more than doubled from 2003–2004 to 2010–2020. This expansion exposes North America to a wider range of insect species that might be introduced, as well as a wider range of individual countries’ effectiveness in enforcing the standard’s requirements (Haack et al. 2022).

These decreases are encouraging. However, Haack et al. (2022) note some caveats:

- The reduction in pest presence was greatest during the initial implementation of the program the first phase, 2005-2006 (61%); in subsequent periods pest approach rate inched back up. In the 2010-2020 period, the pest detection rate was only 36% below the pre-ISPM#15 level. Detection rates have been relatively constant since 2005. Does this stasis mean that exporters learned that they could ignore or circumvent the requirements without suffering significant penalties? Or is some of this rise related to increased trade volumes, increasing variety of country of origin for trade, or other global trade patterns unrecognized in the data? (However, see the next bullet point.)

- Certain types of commercial goods and exporting countries have consistently fallen short. Specifically, the rate of wood packaging from China that is infested remained relatively steady over the 17 years since 2003. The proportion of consignments with infested wood packaging coming from China was more than five times the proportion of all inspected shipments for this period. In other words, China has had a consistent record of poor compliance with phytosanitary regulations since they were imposed in December 1998. Why is USDA not taking action to correct this problem? (As I note below, DHS CBP has ramped up enforcement efforts.) Some other countries, e.g., Italy and Mexico, have reduced the rate at which wood packaging accompanying their consignments is infested. In fact, Mexico’s improved performance largely explains the overall infestation rate estimate of 0.22% during the period 2010-2010. Mexico’s successes affect the overall statistics in a way that makes other countries’ failure to reduce the presence of pests in wood packaging they ship to the United States far less obvious.

Haack et al. (2022) discuss ten possible explanations for their finding that pest approach rates – as determined by their study — have not decreased more. See the article or my blog about the study.

Although USDA APHIS has not taken steps to strengthen its enforcement, U.S. Customs and Border Protection [an agency in the Department of Homeland Security] has done so twice — see here and here. CBP staff have expressed disappointment that these actions reduced the numbers of shipments in violation of ISPM#15 by only 33% between Fiscal Year 2017 and FY2022. True, more than 60% of these violations consisted of a missing or fraudulent ISPM#15 stamp. However, 194 consignments still harbored live pests prohibited under the standard.

APHIS did agree in 2021 to enable the study by Robert Haack and colleagues, via an interoffice data sharing agreement between USDA APHIS and the Forest Service- this resulted in Haack et al. 2022.

APHIS and CBP also collaborated with an industry initiative to train inspectors that insure other aspects of foreign purchases. The ideas was that CBP or APHIS and their Canadian counterparts would inform importers about which foreign treatment facilities have a record of poor compliance or suspected fraud. The importers could then avoid purchasing SWPM from them. I have heard nothing about this initiative for three years, so I fear it has collapsed.

We lack data on which to base a rigorous analysis

While the two studies by Robert Haack and colleagues are the best available, and they relied on the best data available, the fact is that those available data do not provide a full picture of the risk of pest introduction associated with wood packaging. As pointed out by Leigh Greenwood of The Nature Conservancy in her presentation to 2025 USDA Invasive Species Research Forum, available data have been collected for different purposes than to answer this question. Leigh’s powerpoint is posted here.

Leigh has identified the following data gaps:

- In their studies, Haack and colleagues rely on data from the Agriculture Quarantine Inspection Monitoring (AQIM) system. This dataset is based on random sampling of very distinct segments of incoming trade. It is therefore a better measure of insect approach rates than reports of interceptions by either APHIS or CBP.

However, AQIM includes data from only those very distinct segments of trade: perishable goods, SWPM associated with maritime containerized imports, Italian tiles, and “other” goods, AQIM does not contain a segment of trade that includes wood packaging associated with maritime breakbulk or roll-on, roll-off (RORO) cargo. These exclusions have prevented scientists and enforcement officials from determining, inter alia, how great a risk of pest introduction is associated with various types of wood packaging, especially dunnage, as the randomized sample does not include entire pathways for the entrance of dunnage.

Greenwood states that she has not found another country that operates a similar analysis of randomly collected data at ports of entry.

2) USDA does not collect data on consignment size, piece-specific infestation density, nor consignment-wide infestation density. As Haack et al. (2022) point out, reporting detections by consignment doesn’t reveal the number of insects present. If implementation of ISPM#15 resulted in fewer live insects being present in an “infested” consignment, this would reduce the establishment risk because there is lower propagule pressure. However, we cannot know whether this is true.

3) Neither USDA nor CBP reports the inspection effort. Nor do they conduct a “leakage survey” to see how often target pests are missed. This means, inter alia, that we cannot estimate inspectors’ efficiency in detecting infested wood packaging. If their proficiency has improved as a result of improvements in training, inspection techniques, or technology, the apparent impact of ISPM#15 would be under-reported in recent years.

4) USDA does not require port inspectors to report the type of SWPM in which the pest was detected. Leigh participated in an effort that included industry representatives, DHS CBP and USDA APHIS to define the types of wood packaging in legal terminology so that they could be incorporated in the drop-down menu on inspectors’ reporting system. This was first successfully included in the legal glossary within USDA APHIS system of record, ACIR Glossary. Last fall the team was working to integrate the requirement for using these definitions into the inspection data collection system used by DHS CBP, which would then make this data available in Agricultural Risk Management, ARM (see Abstract here for adequate primer on ARM). However, it is unclear now whether the new administration will do so. One potential barrier is that asking the port of entry inspection staff to record these data will add to the time and training required for reporting inspection results.

In summary, Leigh reports that current data systems do not support

- estimating probabilities of pest infestation of via volume or type of SWPM (e.g. pallet vs dunnage)

- measuring the risk of arrival associated with a specific hazard (in this case, a hazard being a live pest or pathogen associated with SWPM)

- extrapolating or supporting findings for some types of wood packaging to other types of wood packaging

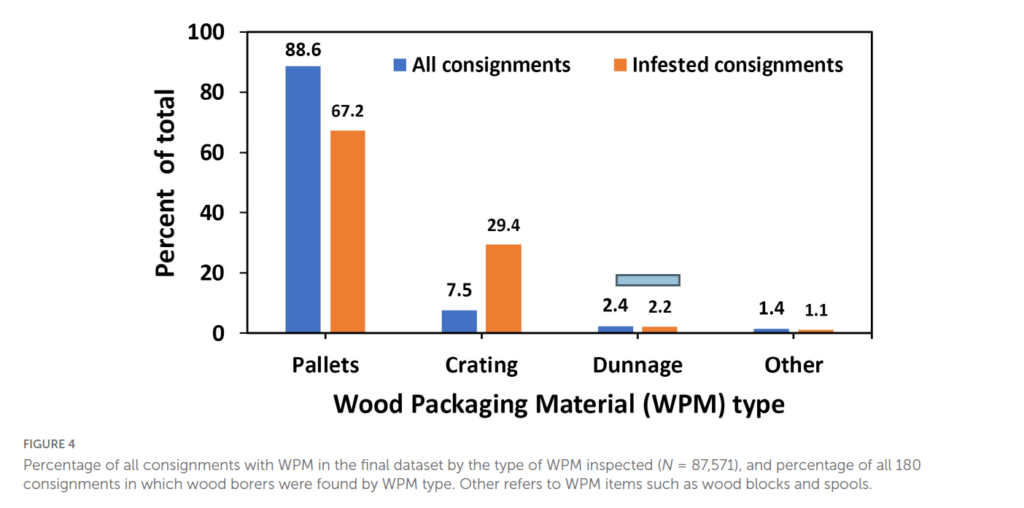

Scientists from Canada, Mexico, and the United States have formed a working group under the auspices of the North American Plant Protection Organization (NAPPO). The group is trying to determine whether various types of wood packaging are more likely to harbor pests. This study is currently hampered by the many data gaps, including those Leigh outlined above. The best data available, cited by Haack et al. (2022), found that in maritime containerized shipping, crates were more likely to harbor pests than pallets- however, other forms of SWPM (dunnage, bracing, etc.) had such low sample size that no analysis of those is possible. One of the main objectives of the NAPPO study is to evaluate if dunnage poses the same or higher risk, so this is a major impediment.

Two issues need to be resolved.

One is scientific: why are insects continuing to be detected in wood packaging marked as having been treated? What is the relative importance of insects surviving the treatment versus treatment facilities applying the treatments incorrectly or inadequately?

The second issue is legal and political: what proportion of the detections is due to treatment facilities committing outright fraud – claiming to treat the wood, stamping it with an IPPC stamp, while not actually performing any treatments at all?

Knowing which measures will most effectively solve these quandaries / reduce pest presence in wood packaging depends on knowing what the relative importance of these factors are in causing the problem. The lack of basic data on which to base any analysis certainly hampers efforts to improve protection.

Leigh calls for researchers to recognize these data needs and work to fill them.

•Understand, account for, and communicate data realities

•Work collectively to increase useable data quality

•Use additional research to validate, or to demonstrate disparities

Why Wait for the Science?

In the meantime, however, I assert that more vigorous enforcement efforts by responsible agencies should help reduce the occurrence of fraud. I have suggested the following actions:

- U.S. and Canada refuse to accept wood packaging from foreign suppliers that have a record of repeated violations – whatever the apparent cause of the non-compliance. Institute severe penalties to deter foreign suppliers from taking devious steps to escape being associated with their violation record.

- APHIS and CBP and their Canadian counterparts follow through on the industry-initiated program described above and here aimed at helping importers avoid using wood packaging from unreliable suppliers in the exporting country.

- Encourage a rapid switch to materials that won’t transport wood-borers. Plastic is one such material. While no one wants to encourage production of more plastic, the Earth is drowning under discarded plastic. Some firms are recycling plastic waste into pallets.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at https://treeimprovement.tennessee.edu/

or