Concerned by growing impacts of bioinvasion and inadequate responses by national governments worldwide and by international bodies, a group of experts have attempted to determine how much invasive species are costing. They’ve built the global database – InvaCost. See Daigne et al. 2020 here.

Several studies have been based on these data. In two earlier blogs, I summarized two of these articles, e.g., Cuthbert et al. on bioinvasion costs, generally, and Moodley et al. on invasive species costs in protected areas, specifically. Here, I look at two additional studies. Ahmed et al. focusses on the “worst” 100 invasives affecting conservation — as determined by the International Union of Conservation and Nature (IUCN). The second, by Turbelin et al., examines pathways of introduction. Full citations of all sources appear at the end of this blog.

It is clear from all of these papers that the authors (and I!) are frustrated by the laxity with which virtually all governments respond to bioinvasions. Thus more robust actions are needed. The authors and I also agree that data on economic costs influence political decision-makers more than ecological concerns. However, InvaCost – while the best source in existence — is not yet comprehensive enough to generate the thoroughly-documented economic data about specific aspects of bioinvasion that would be most useful in supporting proposed strategies.

Scientists working with InvaCost recognize that the data are patchy. At the top level, these data demonstrate high losses and management costs imposed by bioinvasion. The global total – including both realized damage and management costs – is estimated at about $1.5 trillion since 1960. In fact, these overall costs are probably substantially underestimates (Cathbert et al.). [For a summary of data gaps, go to the end of the blog.] Furthermore, they recognize that species imposing the highest economic costs might not cause the greatest ecological harm (Moodley et al).

Comparing estimated management costs to estimated damage, the authors conclude that countries invest too little in bioinvasion management efforts and — furthermore — that expenditures are squandered on the wrong “end” of bioinvasion – after introduction and even establishment, rather than in preventive efforts or rapid response upon initial detection of an invader. While I think this is true, these findings might be skewed by the fact that fewer than a third of countries reporting invasive species costs included data on specifically preventive actions. Cuthbert et al. notes that failing to try to prevent introductions imposes an avoidable burden on resource management agencies. Ahmed et al. developed a model they hope will overcome the perverse incentives that lead decision-makers to either do nothing or delay.

- Why Decision-Makers Delay

Citing the InvaCost data, the participating experts reiterate the long-standing call for prioritizing investments at the earliest possible invasion stage. Ahmed et al. found that this was the most effective practice even when costs accrue slowly. They ask, then, why decision-makers often delay initiating management. I welcome this attention because we need to find ways to rectify this situation.

They conclude, first, that invasive species threats compete for resources with other threats to agriculture and natural systems. Second, Cuthbert et al. and Ahmed et al. both note that decision-makers find it difficult to justify expenditures before impacts are obvious and/or stakeholders demand action. By that time, of course, management of invasions are extremely difficult and expensive – if possible at all. I appreciate the wording in Ahmed et al.: bioinvasion costs can be deceitfully slow to accrue, so policy makers don’t appreciate the urgency of taking action.

Cuthbert et al. also note that impacts are often imposed on other sectors, or in different regions, than those focused on by the decision-makers. Stakeholders’ perceptions of whether an introduced species is causing a “detrimental” impact also vary. Finally, when efficient proactive management succeeds – prevents any impact – it paradoxically undermines evidence of the value of this action!

Ahmed et al. point out that in many cases, biosecurity measures and other proactive approaches are even more cost effective when several species are managed simultaneously. They cite as examples airport quarantine and interception programs; Check Clean Dry campaigns encouraging boaters to avoid moving mussels and weeds; ballast water treatment systems; and transport legislation e.g., the international standard for wood packaging (ISPM#15) [I have often discussed the weaknesses in ISPM#15 implementation; go to “wood packaging” under “Categories” (below the archive list)].

- Pathways of Species’ Introduction

Tuberlin et al. focus on pathways of introduction, which they say influence the numbers of invaders, the frequency of their arrival, and the geography of their eventual distribution. This study found sufficient data to analyze arrival pathways of 478 species – just 0.03% of the ~14,000 species in the full database. They found that intentional pathways – especially what they categorized as “Escape” – were responsible for the largest number of invasive species (>40% of total). On the other hand, the two unintentional pathways called “Stowaway” and “Contaminant” introduced the species causing the highest economic costs.

Tuberlin et al. therefore emphasize the importance of managing these unintentional pathways. Also, climate change and emerging shipping technologies will increase potential invaders’ survivability during transit. Management strategies thus must be adapted to countering these additive trends. They suggest specifically:

- eDNA detection techniques;

- Stricter enforcement of ISPM#15 and exploring use of recyclable plastic pallets (e.g., IKEA’s OptiLedge); [see my blog re: plastic pallets, here]

- Application of fouling-resistant paints to ship hulls;

- Prompt adoption of international agreements addressing pathways (they cite the Ballast Water Management Treaty as entered into force only in 2017 — 13 years after adoption);

- Ensuring ‘pest free status’ (per ISPM#10) before allowing export of goods—especially goods in the “Agriculture”, “Horticulture”, and “Ornamental” trades; and

- Increasing training of interception staff at ports.

What InvaCost Data say re: Taxa of greatest concern to me

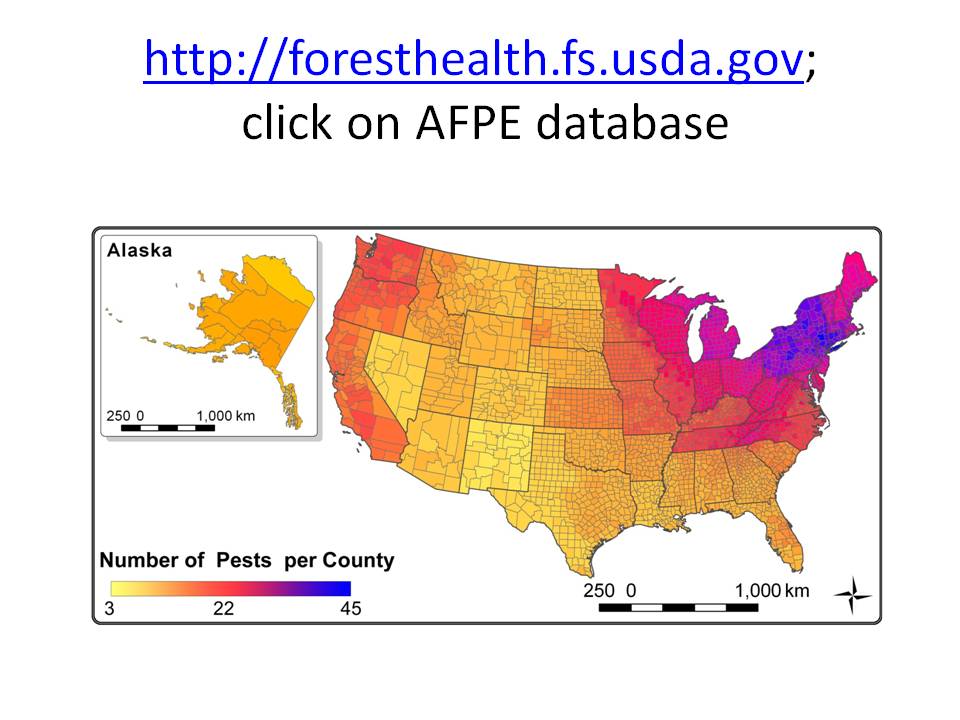

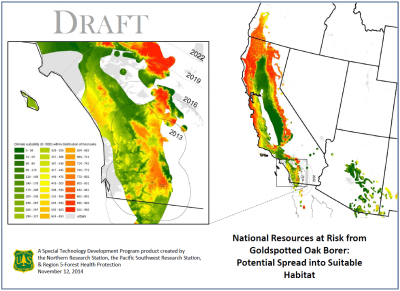

Two-thirds of reported expenditures are spent on terrestrial species (Cuthbert et al.). Insects as a Class constitute the highest number of species introduced as ‘Contaminants’ (n = 74) and ‘Stowaways’ (n = 43). They also impose the highest costs among species using these pathways. Forest insects and pathogens account for less than 1% of the records in the InvaCost database, but constitute 25% of total annual costs ($43.4 billion) (Williams et al., in prep.). Indeed, one of 10 species for which reported spending on post-invasion management is highest is the infamous Asian longhorned beetle (Tuberlin et al.)

Mammals and plants are often introduced deliberately – either as intentional releases or as escapes. Plant invasions are reported as numerous but impose lower costs.

Tuberlin et al. state that intentional releases and escapes should in theory be more straightforward to monitor and control, so less costly. They propose two theories: 1) Eradication campaigns are more likely to succeed for plants introduced for cultivation and subsequently escaped, than for plants introduced through unintentional pathways in semi-natural environments. 2) Species introduced unintentionally may be able to spread undetected for longer; they expect that better measures already exist to control invasions by deliberate introductions. I question both. Their theories ignore that constituencies probably like the introduced plants … and the near absence of attention to the possible need to control their spread. This is odd because elsewhere they recognize conflicts over whether to control or eradicate “charismatic” species.

Geographies of greatest concern to me

- North America reported spending 54% of the total expenditure in InvaCost. Oceania spent 30%. The remaining regions each spent less than $5 billion. (Cuthbert et al.)

- North America funded preventative actions most generously than other regions. Cuthbert suggests this was because David Pimentel published an early estimate of invasive species costs. I doubt it. The Lacey Act was adopted in 1905. USDA APHIS was formed in 1972 – based on predecessor agencies — because officials recognized the damage by non-native pests to agriculture. APHIS began addressing natural area pests with discovery of the Asian longhorned beetle in 1996. Of course, most of APHIS’ budget is still allocated to agricultural pests. I conclude that North America’s lead in this area has not resulted in adequate prevention programs.

Equity Issues

Tuberlin et al and Moodley et al. address equity issues of who causes introductions vs. who is impacted. This is long overdue.

- More than 80% of bioinvasion management costs in protected areas fell on governmental services and/or official organizations (e.g. conservation agencies, forest services, or associations). With the partial exception of the agricultural sector, the economic sectors that contribute the most to movement of invasive species are spared from carrying the resulting costs (Moodley et al.)

- A lack of willingness to invest might represent a moral problem when the invader’s impacts are incurred by regions, sectors, or generations other than those that on whom management action falls (Ahmed et al.)

- People are perhaps more inclined to spend money to mitigate impacts that cause economic losses than those that damage ecosystems (Tuberlin et al.)

Data deficiencies

- Only 41% of countries (83 out of 204) reported management costs; of those, only 24 reported costs specifically associated with pre-invasion (prevention) efforts (Cuthbert et al.).

- Reliable economic cost estimates were available for only 60% of the “worst” invasive species (Cuthbert et al.)

- Only 55 out of 266,561 protected areas reported losses or management costs (Moodley et al.).

- Information on pathways of introduction was available for only three species out of 10,000 (Turbelin et al).

- Taxonomic and geographic biases in reporting skew examples and possibly conclusions (Cuthbert et al.).

SOURCES

Ahmed, D.A., E.J. Hudgins, R.N. Cuthbert, .M. Kourantidou, C. Diagne, P.J. Haubrock, B. Leung, C. Liu, B. Leroy, S. Petrovskii, A. Beidas, F. Courchamp. 2022. Managing biological invasions: the cost of inaction. Biol Invasions (2022) 24:1927–1946 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02755-0

Cuthbert, R.N., C. Diagne, E.J. Hudgins, A. Turbelin, D.A. Ahmed, C. Albert, T.W. Bodey, E. Briski, F. Essl, P. J. Haubrock, R.E. Gozlan, N. Kirichenko, M. Kourantidou, A.M. Kramer, F. Courchamp. 2022. Bioinvasion costs reveal insufficient proactive management worldwide. Science of The Total Environment Volume 819, 1 May 2022, 153404

Moodley, D., E. Angulo, R.N. Cuthbert, B. Leung, A. Turbelin, A. Novoa, M. Kourantidou, G. Heringer, P.J. Haubrock, D. Renault, M. Robuchon, J. Fantle-Lepczyk, F. Courchamp, C. Diagne. 2022. Surprisingly high economic costs of bioinvasions in protected areas. Biol Invasions. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02732-7

Turbelin, A.J., C. Diagne, E.J. Hudgins, D. Moodley, M. Kourantidou, A. Novoa, P.J. Haubrock, C. Bernery, R.E. Gozlan, R.A. Francis, F. Courchamp. 2022. Introduction pathways of economically costly invasive alien species. Biol Invasions (2022) 24:2061–2079 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-022-02796-5

Williams, G.M., M.D. Ginzel, Z. Ma, D.C. Adams, F.T. Campbell, G.M. Lovett, M. Belén Pildain, K.F. Raffa, K.J.K. Gandhi, A. Santini, R.A. Sniezko, M.J. Wingfield, and P. Bonello 2022. The Global Forest Health Crisis: A Public Good Social Dilemma in Need of International Collective Action. Submitted

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or