This February marks 16 years since APHIS began full implementation of ISPM#15. I have blogged often about the failure of ISPM#15 to curtail the risk associated with wood packaging; scroll below the chronological list of blogs to the “categories”, click on “wood packaging”. The best summary of the issues is found in a blog posted in September 2017.

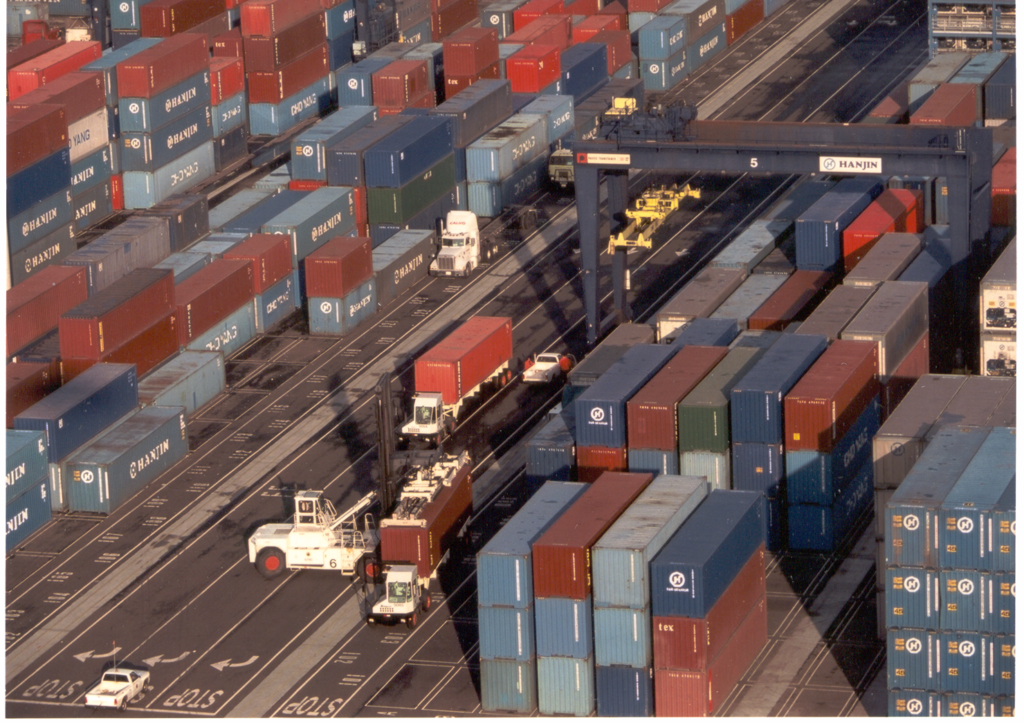

As I have reported in many previous blogs, U.S. imports – especially those from Asia – have been rising since August 2020. Thus, January through October 2021, U.S. imports from Asia are 10.5% higher than the same period in 2020 (Mongelluzzo Dec. 9, 2021). Port officials expect import volumes from Asia to remain high in the first half of 2022, with perhaps a pause in February linked to Asian New Year celebrations (Mongelluzzo Dec. 15 2021). Shipping tonnage devoted to carrying goods from Asia to North America rose by 17% when one compares 2020 to 2021 (Lynch and Wadekar 2021).

These increases are important because of the history of pest introductions in wood packaging from Asia.

This increase is seen most acutely at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which handle about 50% of all U.S. imports from Asia. Such imports during January – November 2021 were 19.4% higher than the same period in 2020; 21.2% higher than during the same period in 2019 (Mongelluzzo Dec. 15 2021).

The rise in imports – and associated pest risk — is not limited to southern California. At the largest port on the East coast – New York/New Jersey – import volumes through October were 20% higher than the same period a year ago. The port is also receiving a higher number of large ships – those carrying 9,000 or more containers (Angell Dec. 22, 2021).

We do not know how many of these containers hold the heaviest commodities most often associated with wood packaging infested by insects — machinery (including electronics); metals; tile and decorative stone (such as marble or granite counter tops). I see many potential links to the COVID-prompted “home improvement” boom. I wonder whether furniture should be included here …

1. 2021 Data on Violations

A recent webinar sponsored by The Nature Conservancy’s Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases and the Entomological Society of America revealed important new information on the pest risk associated with these imports. (Presentations have been posted on the Dialogue’s website). Several of the presentation have particularly significant implications for protecting the US from pests.

Jared Franklin, acting director for agriculture enforcement for DHS’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP), reported that pest detections and shipper violations in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 follow patterns set earlier. There is, however, an interesting decline in numbers of violations despite enhanced inspection intensity. When the number of incoming air passengers crashed because of COVID-19, CBP assigned inspectors to cargo instead.

| Type of violation | FY2018 | FY2019 | FY2020 | FY2021 |

| Lack ISPM#15 mark | 1,662 | 1,825 | 1,662 | 1,459 |

| Live quarantine pest found | 756 | 747 | 509 | 548 |

| TOTAL VIOLATIONS | 2,418 | 2,572 | 2,171 | 2,007 |

Unfortunately, in FY2016 CBP stopped recording whether pests were detected on marked or unmarked SWPM.

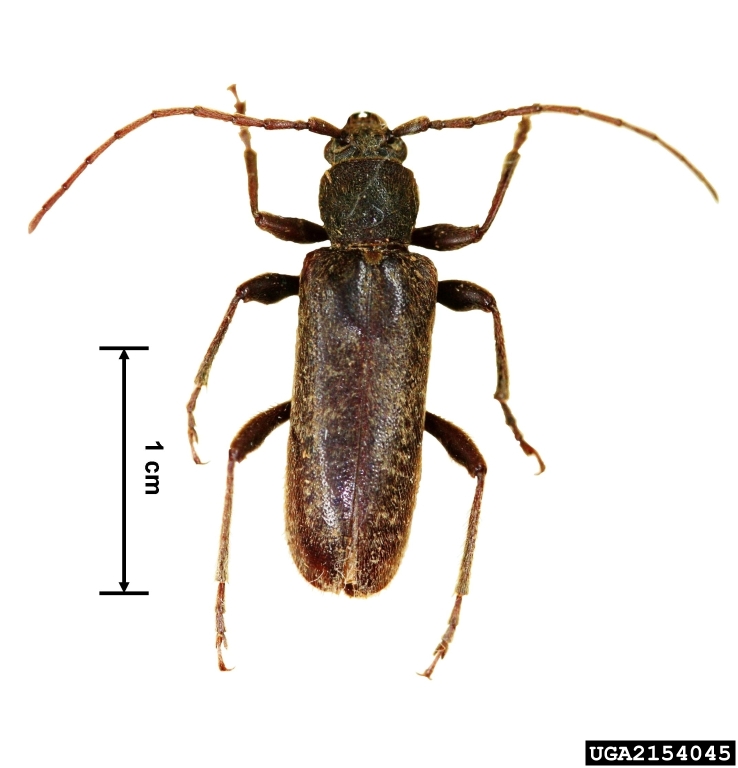

As usual, most of the pests were detected in wood packaging accompanying miscellaneous cargo. Also, as usual, the most commonly detected pests are Cerambycid beetles. During a discussion of why Cerambycids outnumber Scolytids, Bob Haack pointed out that most bark beetles are eliminated by the debarking required by ISPM#15.

2. Updating a Key Study of the Wood Packaging Pathway

Bob Haack revealed that he has received permission to update his earlier landmark study aimed at determining the arrival rate of pests in wood packaging (see Haack et al., 2014). I have long advocated for an update. All my comment about the wood packaging risk have – perforce – relied on this now outdated report. Bob hopes to have results in a few months.

This time, he will work with Toby Petrice (USFS) and Jesse Hardin and Barney Caton (APHIS). While the 2014 study focused on changes in approach rates resulting from U.S.’ implementation of ISPM#15, the new study will presumably uncover current levels of compliance. The authors will use more than 73,000 new port inspection records to detect trends from 2010 through 2020, as well as the original database of about 35,000 inspections made during 2004-2009.

Bob notes that there have been significant changes in ISPM#15 since 2009. These include: a) a requirement that wood be debarked before treatment; b) approval of new treatments (dielectric heat in 2013 and sulphuryl fluoride in 2018); and c) new official definitions of “reuse,” “repair,” and “remanufacturer”.

Besides discovering overall levels of compliance, Bob and colleagues will probably select some aspects of the wood packaging pathway for specific analysis. For example, Dialogue participants want to know whether dunnage has a higher interception rate than pallets. Also, the earlier study included only wood packaging that bore the ISPM mark. This new research might compare live pest interception rates on marked versus unmarked wood.

3) A Study to Improve ISPM#15

Erin Cadwalader reported on the Entomological Society’s Grand Challenge, particularly the request from APHIS that the Society provide guidance on improving ISPM#15. This request was made in 2019; subsequent efforts to conduct a broad scoping process have been complicated and delayed by COVID-19. The goal is to determine what area of effort would lead to either 1) the highest reduction in pest incidence; or 2) the best ISPM#15 compliance.

ESA’s preliminary proposal aims to evaluate the risk associated with various types of wood packaging by analyzing data from five ports over a period of five years. Webinar participants discussed the proposal, especially trying to determine why data already collected by APHIS and CBP – specifically via Agriculture Quarantine Inspection Monitoring (AQIM) – are not adequate to support the study. Another question is whether it is useful for ESA investigators to attempt to rear insects from wood packaging rather than rely on APHIS’ identifications using molecular techniques. Erin noted that some insects – probably particularly small wood borers – might escape detection by inspectors but show up when the wood is placed in rearing chambers.

There will be further discussion of the study’s scope and methodology at the Society’s annual meeting in Autumn 2023 near Washington, D.C. (The 2022 meeting will be in Vancouver; USDA officials rarely get permission to travel to meetings outside the U.S.) ESA estimates that the study will take five years and be completed in 2028.

I am concerned that APHIS might not act on the basis of Bob Haack’s findings as soon as they are available. If they wait for completion of the ESA study, it could be at least six years from now before action is even proposed. I hope that if Haack and colleagues uncover persistent inadequacies in ISPM#15 implementation, APHIS will act unilaterally to address the problem – at least as regards the threat to the U.S. The ESA study might then become the foundation for revising the overall standard per se, that is, the entire world trading system.

Also, APHIS has already carried out a focused study of pests in wood packaging. How can their findings be incorporated into APHIS’ decisions so as to expedite action?

Wu et al. (2017) proved the efficacy of DNA identification tools and that serious pest species continued (at that time) to be present in wood packaging. Krishnankutty et al. (2020) found that 84% of interceptions occurred in wood belonging to only three families: pine, spruce, and poplar. Shipments with coniferous wood came about equally from Europe, Asia, and Mexico. Wood packaging made from poplars came primarily from China. Most of the pests in hardwood were polyphagous, and were considered to pose a higher risk. Pests in softwood samples were mostly oligophagous (feed on two or more genera in the same family). I presume that these findings prompted the studies by Mech et al. and Schulz et al.

As has been true in most studies, pest detections were often associated with shipments of heavy items, such as stone, ceramics, and terracotta; vehicles and vehicle parts; machinery, tools, and hardware; and metal. A high proportion (87%) of the wood packaging bore the ISPM15 mark, also as usual. (Data provided by CBP in past Dialogue meetings showed an even higher proportion of pest-infested wood to be marked.)

Conclusion

Clearly, programs aimed at curtaining the pest risk associated with wood packaging have not been sufficiently effective. I hope APHIS’ approval of Bob Haack’s study and agreement with the Entomological Society indicates a new willingness to understand why and take actions to fix the problems.

SOURCES

Haack, R.A., K.O. Britton, E.G. Brockerhoff, J.F. Cavey, L.J. Garrett. 2014. Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Krishnankutty, S., H. Nadel, A.M. Taylor, M.C. Wiemann, Y. Wu, S.W. Lingafelter, S.W. Myers, and A.M. Ray. 2020. Identification of Tree Genera Used in the Construction of Solid Wood-Packaging Materials That Arrived at U.S. Ports Infested With Live Wood-Boring Insects. Journal of Economic Entomology 2020, 1 – 12

Lynch, D.J. and N. Wadekar. 2021. “Africa left with fallout of US supply chain crisis”. The Washington Post. December 17, 2021.

Mongelluzzo, B. Dec 09, 2021. New long-dwell container fee bearing fruit in Oakland https://www.joc.com/port-news/terminal-operators/new-long-dwell-container-fee-bearing-fruit-oakland_20211209.html?utm_campaign=CL_JOC%20Ports%2012%2F15%2F21%20%20_PC00000_e-production_E-121985_TF_1215_0900&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua

Mongelluzzo, B. Dec. 15 2021. LA port expects imports to surge further in Q2https://www.joc.com/port-news/us-ports/la-port-expects-imports-surge-further-q2_20211215.html?utm_source=Eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=CL_JOC%20Daily%2012/16/21_PC00000_e-production_E-122356_KB_1216_0617

Wu,Y., N.F. Trepanowski, J.J. Molongoski, P.F. Reagel, S.W. Lingafelter, H. Nadel1, S.W. Myers & A.M. Ray. 2017. Identification of wood-boring beetles (Cerambycidae and Buprestidae) intercepted in trade-associated solid wood packaging material using DNA barcoding and morphology. Scientific Reports 7:40316

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm