I am alerting you to two publications about our “favorite” tree-killing pathogen, Phytopthora ramorum (sudden oak death).

The Role of Nurseries in Spreading SOD

The first article informs the general public and raises important questions: “The Diseased Rhododendrons That Triggered a Federal Plant Hunt” by Ellie Shechet in The New Republic.

Ellie reviews the 2019 episode in which P. ramorum-infected rhododendron plants were shipped to retailers in the East and Midwest. Her article is based on interviews with state plant health and APHIS officials, several scientists and advocates (including me), and the executive director of the Oregon Association of Nurseries (OAN). Ellie notes that infected plants were found at more than 100 locations across 16 states.

Ellie notes that despite the risk to native plants in the eastern deciduous forest and the financial cost of implementing control actions (14 million plants were inspected in Washington State alone), plants have a “green” reputation; they are not recognized as potentially causing environmental harm.

The politics of the situation also are reviewed. She writes that the OAN representative has testified that he helped write the more relaxed regulatory approach that APHIS adopted by “federal order” in 2014 and formalized in changes to the regulations in 2019. APHIS denies this. [The article does not include the information that during this period, state regulatory officials detected P. ramorum-infected plants in between four and ten Oregon nurseries each year.] Ellie notes that individual consumers buying plants have few tools to try to ensure that plants they buy are not infected by SOD or other pathogens.

The fact is that the climate in the coastal areas of California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia is conducive to SOD, so the risk of diseased plants being produced there and sold is constant. The current APHIS regulations do not adequately address this, in my view!

Science: High Risk of Phytophthora Introductions from Southeast Asia

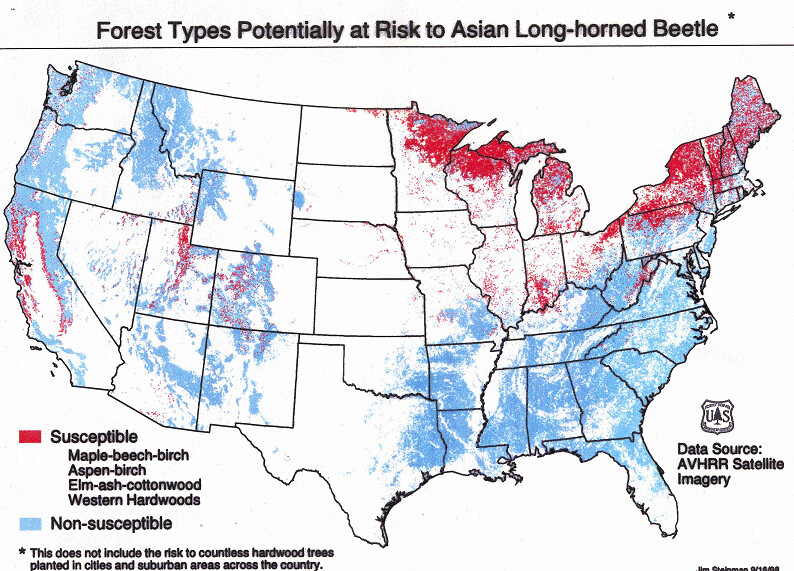

The second article reports results of intense scientific effort: Thomas Jung, Joan Webber, Clive Brasier, and other European plant pathologists report more completely on searches for P. ramorum and other Phytophthora species in East Asia. See the full citation at the end of this blog. [I blogged about their preliminary report a little over a year ago.] Jung et al. conclude that P. ramorum probably originates from the laurosilva forests growing in an arc from eastern Myanmar, across northern Laos, Vietnam, and southwestern China (Yunnan) to Shikoku & Kyushu islands in southwest Japan. The article notes that two other Phytophtoras – P. lateralis (cause of fatal disease on Port-Orford cedar) and P. foliorum – appear to be from the same area. Field science by this team has found 38 previously unknown Phytophthora species in these same forests – and expect that more are present.

They warn that the lack of information about potential pathogens in many developing countries presents a high risk of introduction to naïve environments through burgeoning horticultural trade – especially since the World Trade Organization requires that a species be named and identified as posing a specific threat before phytosanitary regulations can be applied. [I addressed the issue of international phytosanitary rules in Fading Forests II; see the link at the end of the blog.]

Other Pathogen Risks from the Region

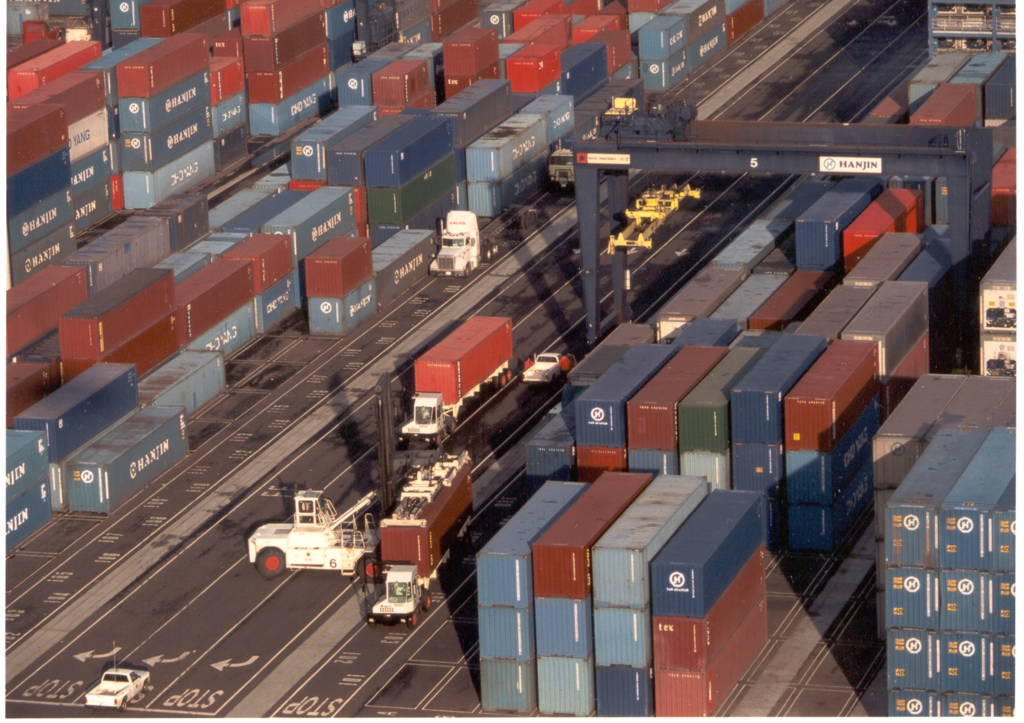

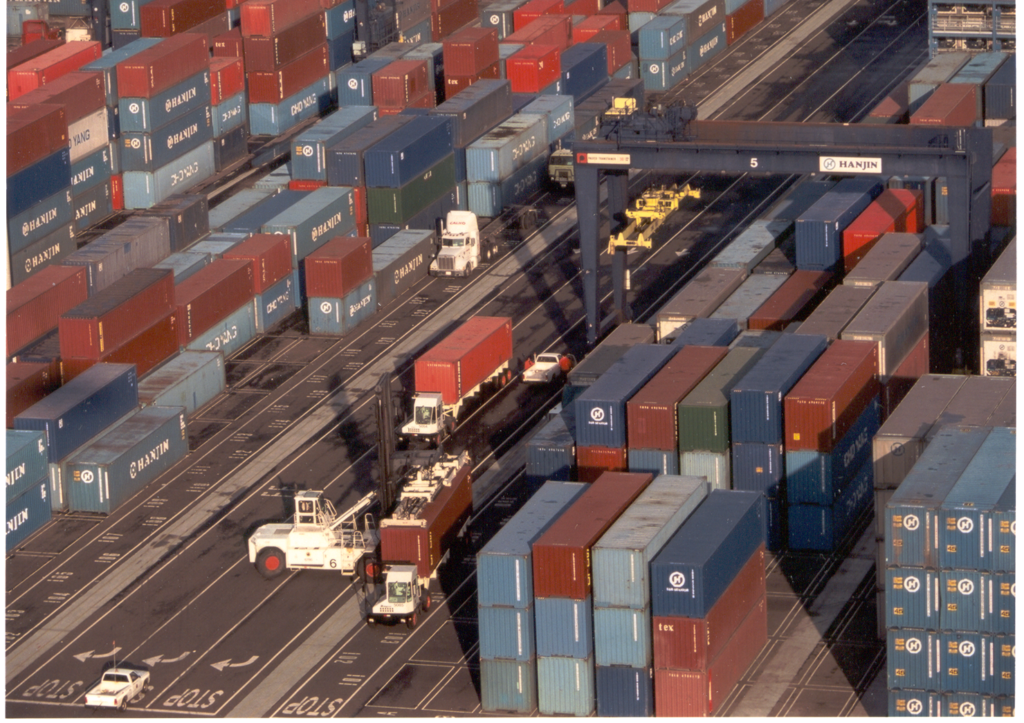

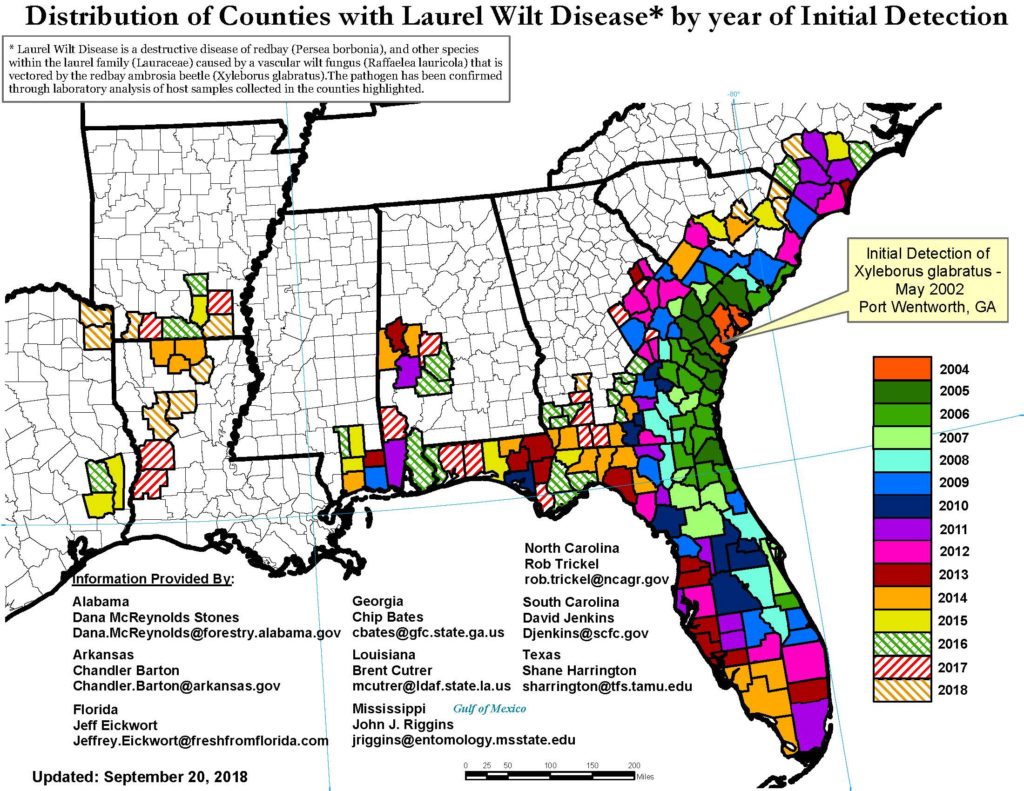

Phytophthoras transported on imported plants are not the only pathogens that could come from Asia. The vectors and associated pathogens causing laurel wilt disease across the Southeast and Fusarium disease in California are believed also to originate in the same region of Asia. Unlike the Phytophthoras, which are transported primarily through the trade in plants for planting, these fungi travel with the vector beetles in wood packaging material. U.S. imports of goods from Asia – often packaged in wooden crates or pallets – have skyrocketed since July 2020. The ports of Los Angeles-Long Beach, which receive 50% of U.S. imports from Asia, handled 6.3 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent containers) from Asia during the period July 2020 through February 2021. The average of close to 800,000 TEU per month for eight consecutive months is unprecedented. Other ports also saw increased import volumes from Asia during this period. [I discussed these shifts in my blog in January.] Imports from Asia in 2020 accounted for 67.4% of total US imports from the world. Imports from China specifically accounted for 42.1% of total US imports. [Data on import volumes is from several reports posted by the Journal of Commerce at its website: https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/]

SOURCE

Jung, T.; Horta Jung, M.; Webber, J.F.; Kageyama, K.; Hieno, A.; Masuya, H.; Uematsu, S.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Harris, A.R.; Forster, J.; et al.. The Destructive Tree Pathogen Phytophthora ramorum Originates from the Laurosilva Forests of East Asia. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ open access!

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm