photo by Joseph O’Brien. courtesy of Bugwood

We know that the international trade in living plants is a major pathway by which tree-killing pathogens are being spread – some of them again and again. According to Grünwald et al. (2019), Phytophthora ramorum, the pathogen that causes Sudden Oak Death (SOD), has been introduced to North America and Europe – probably from Asia – at least five times. One lineage or genetic strain – EU1 – has been established on both continents (strains explained here). There is strong evidence of two separate introductions to Oregon, at least 12 to California.

Jung et al. 2015 state definitively that the international movement of infested nursery stock and planting of reforestation stock from infested nurseries have been the main pathway of introduction and establishment of Phytophthora species in European forests.

photo from UK Forest Research

Jung et al. 2020 have demonstrated that P. ramorum probably originated in Vietnam. This region appears to be a center of diversity for Phytophtoras and other Oomycetes: baiting of soil and streams resulted in the detection of 13 described species, five informally designated taxa, and 21 previously unknown taxa of Phytophthoras plus at least 15 species in other genera. Noting the risk associated with any trade in plants from this region, the authors re-iterated past appeals that the international phytosanitary system replace the “outdated and scientifically flawed species-by-species regulation approach based on random visual inspections for symptoms of described pests and pathogens” by instituting “a sophisticated pathway regulation approach using pathway risk analyses, risk-based inspection regimes and molecular high-throughput detection tools.”

Pathogen’s Spread Proves U.S. Domestic Regulations Governing Nursery Trade Are Inadequate

Last year I blogged about the most recent spread of Phytophthora ramorum through the nursery trade. As of now, we know that shipments of potentially infected plants had been sent to 18 states. Infected stock had been detected in nurseries in seven of these (Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma) plus the source state, Washington [COMTF Newsletter August 2019].

Since then, I learned [COMTF newsletter for December 2019] that these plants were infected by the NA2 strain of the pathogen. This is the first time that this strain has been shipped to states outside the West Coast. It is unclear what the impact will be if – as is likely – infested plants are still extant in purchasers’ yards. Both the NA1 strain (the strain established in most infested forests of California and Oregon) and the NA2 strain belong primarily to the A2 mating type, so the potential spread of NA2 lineages might not exacerbate the probability of sexual reproduction of the pathogen.

I applaud agencies’ funding of genetic studies to determine the lineage of the pathogen involved. It not only helps narrow the possible sources of infected plants, but also could be important in determining risk and management options.

I have long criticized USDA’s P. ramorum regulatory program – see Fading Forests III and my blogs discussing the most recent revisions to the regulations here and here. I believe that both the earlier regulations and the revisions finalized last May provide inadequate protection for America’s forests.

The updated regulations do take a couple of important positive steps. First, APHIS is now authorized to sample water, soil, pots, etc. – and to act when it finds evidence of the pathogen’s presence. APHIS also now mandated nurseries found to be infested to carry out a “critical control point analysis” to determine practices which facilitated establishment and persistence of P. ramorum.

However, these improvements are severely undermined by continuing the five-year-old practice of limiting close scrutiny to only those nurseries that tested positive for the pathogen in the recent past. The flaw in this approach was starkly demonstrated by the pathogen’s spread in 2019. The Washington State nursery that was the source of the infected plants had not previously been positive, so it was under routine nursery regulation, not the more stringent federal P. ramorum program.

Too often various iterations of the regulations have allowed infected plants to be shipped. Between 2003 and 2011, a total of 464 nurseries located in 27 states tested positive for the pathogen, the majority as a result of shipments traced from infested wholesalers (Campbell). The number of nurseries found to have infected plants has since declined, but not dropped to zero. These include 34 nurseries in 2010 (COMTF February 2011 newsletter), 21 in 2012, and 17 in 2013 (Pfister). During 2014, state inspectors detected the SOD pathogen in 19 nurseries – 11 in the three west-coast states and eight in other parts of the country (Maine-1, New York-2, Texas-1, and Virginia-4) COMTF newsletter December 2014). Despite the continuing presence of the pathogen in the nursery trade, APHIS formalized existing practices that narrowed the regulators’ focus to only those nurseries with a history of pathogen presence. This approach has been shown to fail – we need APHIS and the states to find a way to broaden their scrutiny.

The most immediate impact of the continuing presence of P. ramorum in the nursery trade is the burden borne by eastern states’ departments of agriculture. They are obligated to seek out in-state nurseries that might have received infected plants; inspect those plants; and destroy the infected plants, test nearby plants, and try to find and retrieve plants that had been sold. The heaviest, and most direct, burden is borne by the receiving nurseries. Anger about bearing this burden for 15 years doubtless prompted the National Plant Board to adopt a tart resolution calling on APHIS to carry out a review of its communications to the states during the 2019 incident. The NPB also questioned whether current program processes and guidance are effective in preventing spread of this pathogen.

Unfortunately, the NPB had not commented formally on the rule change when it was proposed.

The states’ frustration is exacerbated by the fact that under the Plant Protection Act, when APHIS takes a regulatory action it prevents states from adopting more stringent regulations. While the law allows for exceptions if the state can demonstrate a special need, none of the five applications for an exemption pertaining to P. ramorum was approved (Porter and Robertson 2011). I have been unable to find evidence of petitions submitted in the nine years since 2011.

In Case You Needed A Reminder: P. ramorum is a Dangerous Pathogen – as Proved by the Situation in the West states and Abroad

Continuing Intensification of the Already Bad Infestations in the West

photo courtesy of Matteo Garbelotto, UC Berkeley

As of 2014 (see COMTF November 2018 newsletter available here), perhaps 50 million trees had been killed by P. ramorum in California and Oregon. The vast majority were tanoaks (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) – an ecologically important tree.

Since 2014, the disease has intensified and spread in response to recent wet winters. In 2016 (see COMTF

November 2016 newsletter here) disease was detected for the first time in a fifteenth California county and new outbreaks or more severe infestations were recorded in seven other counties. In 2019, SOD was detected in the sixteenth county. Tanoak mortality in California increased by more than 1.6 million trees across 106,000 acres in 2018.

Perhaps more disturbing, the disease has also intensified on the eastern side of San Francisco Bay – an area thought to be less vulnerable because it is drier and where there are fewer of the principal sporulation host, California bay laurel (see COMTF March 2017 newsletter here).

A second disturbing event is the detection in Oregon forests of the EU1 strain of Phytophthora ramorum. The August 2015 detection was the first instance of this strain being detected in a forest in North America. Oregon authorities prioritized removing EU1-infected trees and treating (burning) the immediate area, which had expanded to more than 355 acres – all within the quarantine area in Curry County. The legislature provided $2.3 million for SOD treatments for 2017-2019 (Presentation by Chris Benemann of Oregon Department of Agriculture to the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases; reported here).

The EU1 lineage is a different mating type than the NA1 lineage already established in Oregon. Scientists should study P. ramorum populations in Vietnam and Japan, where both mating types are present, to determine whether they are reproducing sexually. There is also the risk that the EU1 lineage might be more aggressive on conifers – as it has been in the United Kingdom (Grünwald et al. 2019).

The EU1 infestation was introduced to the forest from a nursery. The nursery had carried out the APHIS-mandated Confirmed Nursery Protocol, then closed. I ask, what does this apparent transmission from nursery to forest say about the risk of transmission? Does it raise questions about the efficacy of the confirmed nursery protocol to clean up the area? Remember that a pond at the botanical garden in Kitsap, Washington has repeatedly tested positive, despite several applications of the clean-up protocols.

(For a discussion of the implications of mixing the various strains of P. ramorum, visit here)

These disasters remind us how sad it is that California and federal officials did not adopt aggressive management efforts aimed at slowing the pathogen’s spread at an early stage of the epidemic. Experts on modeling the epidemiology of plant disease concluded three years ago that the sudden oak death epidemic in California could have been slowed considerably if aggressive and well-funded management actions had started in 2002 (Cunniffe, Cobb, Meentemeyer, Rizzo, and Gilligan 2016).

The Oregon Department of Forestry commissioned a study of the economic impact of the P. ramorum infestation that found few economic impacts to date, but potentially significant impacts in the future. It also noted potential harms to tribal cultural values and the “existence value” of tanoak-dominated forests and associated obligate species.

Situation Abroad

The situation in Europe is even worse than in North America. Two strains of P. ramorum are widespread in European nurseries and in tree plantations and wild heathlands of western the United Kingdom and Ireland. and here and here. Jung et al. 2015 found 56 Phytophthora taxa in 66% of 2,525 forest and landscape planting sites across Europe that were probably introduced to those sites via nursery plantings.

photo from UK Forest Research

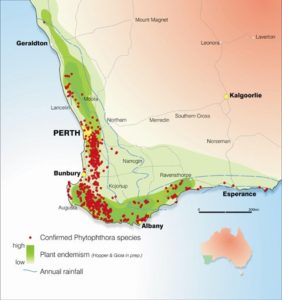

In Australia, Phytophthora dieback has infected more than one million hectares in Western Australia. More than 40% of the native plant species of the region are vulnerable to the causal agent, P. cinnamomi

and here.

Barber et al. 2013 reported 9 species of Phytophthora associated with a wide variety of host species in urban streetscapes, parks, gardens, and remnant native vegetation in urban settings in Western Australia. Phytophthora species were recovered from 30% of sampled sites.

In New Zealand, the endemic – and huge, long-lived – kauri tree (Agathis australis) is also suffering severe impacts from Phytophtoras and other pathogens (Bradshaw et al. 2020)

See the IUFRO Working Party 7.02.09 ‘Phytophthora Diseases of Forest Trees’ global overview (Jung et al. 2018), which covers 13 outbreaks of Phytophthora-caused disease in forests and natural ecosystems of Europe, Australia and the Americas.

The situation in the Eastern United States is Unclear

After 15 years of the nursery trade carrying P. ramorum to nurseries – and possibly yards and other plantings – in states east of the 100th Meridian, what is the risk that these forests will become infested? No one knows. We do known that the pathogen has been detected from 11 streams in six eastern states – four in Alabama; one in Florida; two in Georgia; one in Mississippi; one in North Carolina; and two in Texas. P. ramorum has been found multiple times in eight of these streams – two steams in Alabama, one each in Mississippi and North Carolina (see COMTF April 2019 newsletter available here). While established vegetative infections have not been detected, the question remains: how is the pathogen persisting? Scientists agree that P. ramorum cannot persist in the water; it must be established on some plant parts (roots?) or in the soil. Still, Grünwald et al. (2019) report that there is little evidence of plant infections resulting from stream splash in Oregon.

Unfortunately, fewer states are participating in the stream surveys – which are operated by the USDA Forest Service. In 2010, 14 states participated; in 2018, only seven (Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Texas). Florida and Tennessee recently dropped out. The number of streams surveyed annually also has dropped – from 95 at the highest to only 47 in 2018 (see COMTF April 2019 newsletter available here). This reduced scrutiny makes it less likely that any infestation on plants will be detected. Risk maps (reproduced in Chapter 5 of Fading Forests III here) developed over more than a decade indicate that forests in the southern Appalachians and Ozarks are vulnerable to SOD.

Risks to other plants

The risk from Phytophthoras is not just P. ramorum and trees! Swiecki et al. 2018 report a large and increasingly diverse suite of introduced Phytophthora species pose an ever greater threat to both urban and non-urban plant communities in California. These threats are linked to planting of nursery stock. See also the information posted here.

Jung et al. 2018 cite numerous other authors’ findings of multiple Phytophthoras in Oregon and. California nurseries as well as in nurseries in various eastern states.

Nor is Phytophthoras the only pathogenic genus to pose a serious risk to America’s trees. I remind you of the fungus Fusarium euwallacea associated with the Kuroshio and polyphagous shot hole borers, which is known to kill at least 18 species of native plants in California and additional species in South Africa. The laurel wilt fungus kills many trees and shrubs in the Lauraceae family. ‘Ohi‘a or myrtle rust kills several shrubs native to Hawai`i and threatens a wide range of plants in the Myrtaceae family in Australia and New Zealand; rapid ‘ohi‘a death fungi (Ceratocystis huliohia and Ceratocystis lukuohia) [All described here] are killing the most widespread tree on the Hawaiian Islands.

Solutions – complete & implement modernized international and domestic phytosanitary regulations

Clearly, standard phytosanitary practice of regulating pests known to pose a threat does not work when many – if not most – of the damaging pests are unknown to science until introduced to a naïve ecosystem where they start causing noticeable levels of damage. We need a more proactive approach – as has long been advocated by forest pathologists, including Clive Brasier 2008 and later, Santini et al. 2013, Jung et al. 2016, Eschen et al. 2017.

National and international phytosanitary agencies have taken some steps toward adopting policies and programs that all hope will be more effective in preventing the continued spread of these highly damaging tree-killing pests. First, APHIS has had authority since 2011 – through the Not Authorized for Importation Pending Pest Risk Assessment (NAPPRA) program — to prohibit temporarily imports of plants suspected of transporting known damaging pathogens until the agency has conducted a pest risk analysis. However, utilization has lagged: only three sets of species have been proposed for listing in NAPPRA in the eight and a half years since the program was instituted in 2011. The third list of proposed species is currently open for public comment.

Another weakness is that the program still focuses on organisms known to pose a risk.

Second, in 2018 APHIS completed a decades-long effort to revise its plant import regulations (the “Q-37” regulations). APHIS now has authority to require foreign suppliers of living plants to carry out “hazard analysis and critical control point” programs and adopt integrated pest management strategies to ensure that the plants are pest-free during production and transport.

However, implementation of this new authority depends on APHIS negotiating agreements with individual countries that would govern specific types of plants exported to the U.S. APHIS has not yet announced completion of any programs under this authority. Nor is it clear which taxa or countries APHIS will prioritize.

APHIS’ action was anticipated by the international plant health community. In 2012, member states in the International Plant Protection Convention adopted International Standard for Phytosanitary Measure 36 (ISPM#36) The standard sets up a two-level system of integrated measures, which are to be applied depending on the pest risk identified through pest risk analysis or a similar process. The “general” integrated measures are widely applicable to all imported plants for planting. The second level includes additional elements designed to address higher pest-risk situations that have been identified through pest risk analysis or other similar processes.

However, the preponderance of international efforts to protect plant health continues to rely on visual inspections that look for species on a list of those known to be harmful. Yet we know that most damaging Phytophthoras were unknown before their introduction to naïve ecosystems.

Furthermore, use of fungicides and fungistatic chemicals – that mask infections but do not kill that pathogen – is still allowed before shipment.

(For more complete analyses of the Q-37 revision and ISPM#36, see chapters five and four, respectively, of Fading Forests III.)

The nursery industry is working with state regulators and APHIS to develop a voluntary program utilizing integrated measures – the Systems Approach to Nursery Certification (SANC) program. https://sanc.nationalplantboard.org/

SOURCES

Bradshaw et al. 2020. Phytophthora agathidicida: research progress, cultural perspectives and knowledge gaps in the control and management of kauri dieback in New Zealand. Plant Pathology (2020) 69, 3–16 Doi: 10.1111/ppa.13104

Brasier CM. 2008. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology 57: 792–808.

Brasier, C.M, S. Franceschini, A.M. Vettraino, E.M. Hansen, S. Green, C. Robin, J.F. Webber, and A.Vannini. 2012. Four phenotypically and phylogenetically distinct lineages in Phytophthora lateralis

Fungal Biology. Volume 116, Issue 12, December 2012, Pages 1232–1249

Campbell, F.T. Calculation by F.T. Campbell from tables in U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – National Plant Board. 2011. Phytophthora ramorum Regulatory Working Group Reports. January 2011.

Cunniffe, N.J., R.C. Cobb, R.K. Meentemeyer, D.M. Rizzo, and C.A. Gilligan. Modeling when, where, and how to manage a forest epidemic, motivated by SOD in Calif. PNAS, May 2016 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1602153113

Grünwald, N.J., J.M. LeBoldus, and R.C. Hamelin. 2019. Ecology and Evolution of the Sudden Oak Death Pathogen Phytophthora ramorum. Annual Review of Phytopathology date? #?

Jung T, Orlikowski L, Henricot B, et al. 2016. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. Forest Pathology 46: 134–163.

Jung, T., A. Pérez-Sierra, A. Durán, M. Horta Jung, Y. Balci, B. Scanu. 2018. Canker and decline diseases caused by soil- and airborne Phytophthora species in forests and woodlands. Persoonia 40, 2018: 182–220 Open Access!

Jung, T. et al. 2015. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora disease. Forest Pathology. November 2015; available from Resource Gate

Jung, T., B. Scanu, C.M. Brasier, J. Webber, I. Milenkovic, T. Corcobado, M. Tomšovský, M. Pánek, J. Bakonyi, C. Maia, A. Baccová, M. Raco, H. Rees, A. Pérez-Sierra & M. Horta Jung. 2020. A Survey in Natural Forest Ecosystems of Vietnam Reveals High Diversity of both New and Described Phytophthora Taxa including P. ramorum. Forests, 2020, 11, 93 https://gcc02.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mdpi.com%2F1999-4907%2F11%2F1%2F93%2Fpdf&data=02%7C01%7C%7Cfcd843919a3348a4a56108d7974039ab%7Ced5b36e701ee4ebc867ee03cfa0d4697%7C0%7C1%7C637144174418121741&sdata=WayrZsxp3P9Kj0h1aDPZnzu4yjDGA2ZEuH9NZITFQF4%3D&reserved=

Knaus, B.J., V.J. Fieland, N.J. Grunwald. 2015. Diversity of Foliar Phytophthora Species on Rhododendron in Oregon Nurseries. Plant Disease Vol 99, No. 10 326 – 1332

Pfister, S. USDA APHIS. Presentation to the National Plant Board, August 2013

Porter, R.D. and N.C. Robertson. 2011. Tracking Implementation of the Special Need Request Process Under the Plant Protection Act. Environmental Law Reporter. 41.

Santini A, Ghelardini L, De Pace C, et al. 2013. Biogeographic patterns and determinants of invasion by alien forest pathogens in Europe. New Phytologist 197: 238–250.

Swiecki, T.J., E.A. Bernhardt, and S.J. Frankel. 2018. Phytophthora root disease and the need for clean nursery stock in urban forests: Part 1 Phytophthora invasions in the urban forest & beyond. Western Arborist Fall 2018

Tsao PH. 1990. Why many Phytophthora root rots and crown rots of tree and horticultural crops remain undetected

Ailanthus altissima

Ailanthus altissima