dead ash killed by emerald ash borer; photo by Dan Herms, The Ohio State University; courtesy of Bugwood.com

I have blogged often about the funding crisis hampering APHIS’ efforts to protect our forests from damaging insects and pathogens (visit www.cisp.us, scroll down to “categories”, then scroll down to “funding”). Apparent results of this funding crisis include APHIS’ failure to adopt official programs to address several tree-killing pests (e.g., polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers, goldspotted oak borer, spotted lanternfly …) and its proposal this month to end the regulatory program intended to slow the spread of the emerald ash borer (available here.) (All these tree-killing pests are described here.)

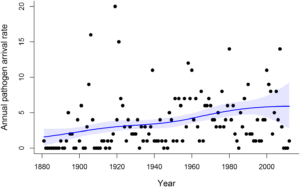

The lack of adequate resources plagues phytosanitary programs in many countries as well as at the international and regional level. As we know, the threat of introduction and spread of plant pests is growing as a result of increasing trade volume and transportation speed; increasing variety of goods being traded; and the use of containers. All countries and international bodies should be expanding efforts to address this threat, not cutting back.

Assuming you agree with me that preventing and responding to damaging plant pests is important – a task which falls within the jurisdiction of phytosanitary institutions – what more can we do to raise decision-makers’ and opinion leaders’ understanding and support? Should we join phytosanitary officials’ efforts – e.g., the International Year of Plant Health – or act separately?

How do we encourage greater engagement by such entities as professional and scientific associations, the wood products industry, state departments of agriculture, state phytosanitary officials, state forestry officials, forest landowners, environmental organizations and their funders, urban tree advocacy and support organizations. (The Entomological Society of America has engaged on invasive species although it remains unclear to me whether ESA will advocate for stronger policies and higher funding levels.)

There is one group making serious, multi-year efforts to respond. Here, I describe efforts by the International Plant Protection Convention’s (IPPC) governing body, the Commission on Phytosanitary Measures. The Commission has recognized the crisis and is attempting to reverse the situation through a coordinated strategy. I invite you to consider how we all might take part in, and support, its efforts.

Efforts of the IPPC Commission on Phytosanitary Measures

The Commission’s goal is to ensure that strong and effective phytosanitary programs “become a national and global priority that justifies and receives appropriate and sustainable support.” It seeks to achieve this by convincing decision-makers that protecting plant health from pest threats is an essential component of efforts to meet other, more broadly accepted goals, specifically the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) related goals (described here).

The IPPC Commission also sees that, to succeed, it must more effectively support member countries in improving their programs to curtail pests’ spread and impacts. IPPC plans to streamline operations and integrate more closely with other FAO work in order to save money.

The following are among Commission efforts, although all are hampered by the lack of funding:

- Working with member countries, the Commission has persuaded the United Nations to declare 2020 the International Year of Plant Health. (I blogged about this campaign in December 2016.

- Describing links between plant health and other policy goals. The Commission is mid-way through a multi-year program. One outcome has been presentations to member states’ phytosanitary officials attending the Commission’s annual meetings, each focusing on one specific aspect. In 2018, presentations focus on links between plant health and environmental protection (presentations from April 2018 are available here). (Did you know 2018 was the year of plant health and the environment? I didn’t!) In 2016, the topic was plant health’s link to food security; in 2017, plant health and trade facilitation; in 2019, capacity development for ensuring plant health.)

- Adopting a Communications Strategy. It has four broad objectives (available here).

- increase global awareness of the importance of the IPPC and of the vital importance to the world of protecting plants from pests;

- highlight the IPPC’s role as the sole international plant health standard setting organization aimed at improving safety of trade of plants and plant products and improving market access;

- improve implementation of IPPC’s international standards (ISPMs); and

- support the activities of the IPPC Resource Mobilization program.

- Ramping up efforts to support implementation of its international standards. Since this 2014 decision, the Commission has conducted some pilot projects, restructured the Secretariat, and formed the Implementation and Capacity Development Committee. (I have blogged frequently about issues undermining one of those standards, the one on wood packaging material – ISPM#15. Visit www.cisp.us, scroll down to “categories”, then scroll down to “wood packaging”.)

Framework 2020-2030: the IPPC Strategic Plan

Framework 2020-2030: the IPPC Strategic Plan

The IPPC is now finalizing its strategic plan (Framework 2020-2030), which is available here. APHIS circulated this plan in July for comment; I admit did not take the opportunity to comment because I could think of nothing to add. But now I want to link the international and domestic U.S. funding crises.

The plan describes how plant pests threaten

- food production at a time rising human population and demand;

- sustainable environments and ecosystem services at a time when recognition is growing of their importance for managing climate change and meeting food production goals;

- free trade and associated economic development;

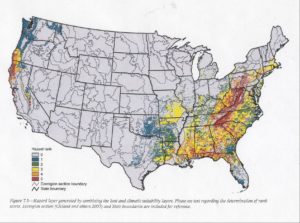

The plan notes that interactions between climate change and pests’ geographic ranges and impacts complicate efforts to address both threats. Also, it outlines the need for, and barriers hindering, collaborative research on plant pest. It suggests creation of an international network of diagnostic laboratories to support reliable and timely pest identifications.

The plan states several times that the IPPC is “the global international treaty for protecting plant resources (including forests, aquatic plants, non-cultivated plants and biodiversity) from plant pests …” (emphasis added). The Commission is attempting to improve its efforts to protect the environment through expanding its collaboration with the Convention on Biological Diversity, Global Environmental Facility and the Green Climate Fund. Much of the attention to environmental concerns is focused on interactions with climate change, followed by concerns about pesticide use. Indeed, the strategic plan states that “Political weight and subsequent funding for phytosanitary needs on national, regional and international level will only be available when phytosanitary issues are recognized as an important component of the climate change debate.”

The Plan describes other ways that the Commission and regional plant protection organizations might help countries overcome the major problems arising from their lack of capacity and resources. Another area of hoped-for activity is promoting collaborative research. All these proposals depend on finding funding.

However, the Strategic Plan does not reveal the extent to which its 2013 Communications Strategy has been implemented. Nor does it reveal the extent to which the effort to improve ISPM implementation has resulted in concrete progress.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

P. ramorum-infected seedlings in a nursery; photo by USDA APHIS

P. ramorum-infected seedlings in a nursery; photo by USDA APHIS

laurel-wilt killed swamp bay in the Everglades

laurel-wilt killed swamp bay in the Everglades