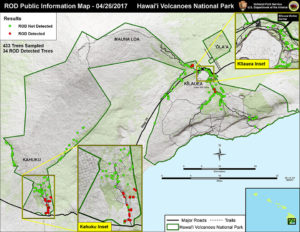

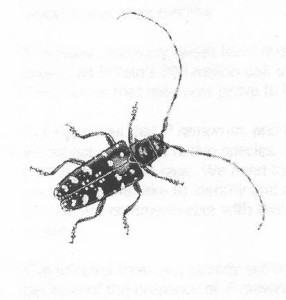

citrus longhorned beetle – entered country several times in imported bonzai plants

citrus longhorned beetle – entered country several times in imported bonzai plants

After about 20 years, APHIS has finalized important changes to the regulations which govern imports of living plants (what they call “plants for planting”; the regulation is sometimes called “the Quarantine 37” rule). The new regulation takes effect on April, 18, 2018.

I congratulate APHIS on this important achievement!

[Twenty years is a long time – so changes happen. When APHIS released its Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) in December 2004 and its proposed rule in April 2013, I was employed by The Nature Conservancy and submitted comments for that organization. I will refer to those earlier comments in this blog. However, I now represent the Center for Invasive Species Prevention, so my comments here on the final regulations reflect the position of CISP, not the Conservancy.]

APHIS’ 2004 ANPR came after years of preparation. Then, more than eight years passed until the formal proposal was published on April 25, 2013. Comments were accepted from the public until January 30, 2014. During this nine-month period, 17 entities commented, including producers’ organizations, state departments of agriculture, a foreign phytosanitary agency (The Netherlands), private citizens, and The Nature Conservancy. [You can view the ANPR and proposal, comments on these documents, and APHIS’ response here — although you need to click on “Restructuring of Regulations on the Importation of Plants for Planting” and then “Open Docket Folder” to pursue the older documents.]

In the beginning, APHIS had a few goals it hoped to achieve: to allow the agency to respond more quickly to new pest threats, to apply practices that are more effective at detecting pests than visual inspection at points of import, and to shift much of the burden of preventing pest introductions from the importer and APHIS to the exporter.

Progress has been made toward some of these goals outside this rule-making. APHIS instituted a process to temporarily prohibit importation of plants deemed to pose an identifiable risk until a pest risk assessment has been completed (the NAPPRA process). APHIS has further enhanced its ability to act quickly when a pest risk is perceived by relying increasingly on “Federal Orders”.

At the same time, APHIS participated actively in efforts by international phytosanitary professionals to adopt new “standards.” These define a new approach to ensure that plants in international trade are (nearly) pest-free. Both the North American Plant Protection Organization’s regional standard (RSPM#24) and the International Plant Protection Organization’s global standard (ISPM#36) envision a system under which countries would no longer rely primarily on inspections at ports-of-entry. Instead, they would negotiate with the supplier or exporting country to develop programs to certify that growers’ pest management programs are effective. Both standards detailed: 1) how the place of production might manage pest risk and ensure traceability of plants; 2) how the importing and exporting countries might collaborate to administer the program; 3) how audits (including site visits) would ensure the program’s efficacy; and 4) what actions various parties might take in cases of noncompliance.

It was hoped that these international standards would lead to widespread adoption of “integrated pest management programs” composed of similar requirements – similar to the impact of ISPM#15 for wood packaging. However, living plants are more complex pest vectors than the wooden boards of crates and pallets, so each country was expected to negotiate its own specific programs – something not encouraged for wood packaging.

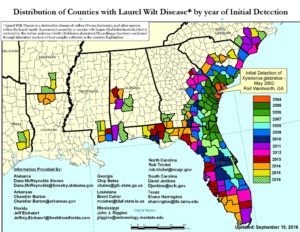

APHIS’ decades-long effort to amend its regulations is warranted because of the high risk of non-native insects and – especially – pathogens being introduced via international trade in living plants. U.S. examples include white pine blister rust, chestnut blight, dogwood anthracnose, and sudden oak death (all described briefly here )

According to Liebhold et al. 2012 (full reference at end of blog), 12% of incoming plant shipments in 2009 were infested by a quarantine pest. This is an approach rate that is 100 times greater than the 0.1% rate documented for wood packaging (Haack et al. 2014). I have discussed the living plant introductory pathway and efforts up to 2014 to get it under control in my report, Fading Forests III.

Shortcomings of the Final Q 37 Rule

So – how well does this final rule meet APHIS’ objectives?

First, will it shift much of the burden of preventing new pest introductions from the importer and APHIS to the exporter, while ensuring the system’s efficacy? In my view, on behalf of CISP, it falls short.

The new rule sets up a process under which APHIS might require that some types of imported plants be produced and shipped under specified conditions intended to reduce pest risk. However, non-American entities have little incentive to protect America’s natural and agricultural resources and from invasive species. So any new process needs severe penalties for violators.

We have seen how widespread and persistent compliance failures are for wood packaging under ISPM#15. http://nivemnic.us/wood-packaging-again-11-years-after-ispm15-problems-persist/ For this reason, I (on behalf of the Conservancy) had suggested that APHIS formally adopt a specific goal of “no new introductions”. I recognized that this goal was unachievable per se, but suggested that it should stand as a challenge and be the basis for adopting stringent restrictions on plant imports. I suggested limiting plant imports to those either a) produced under integrated pest management measures systems (verified by third-party certification) or b) plants brought into facilities operating under post-entry quarantine conditions — and following other best management practices that had been developed and supervised by independent, scientifically-based bodies.

In my current view, APHIS’ regulation falls far short of either this goal of shifting burdens or setting a truly stringent requirement. In fact, APHIS has explicitly backed away from its own original goals and procedures.

The new regulation does authorize APHIS to choose to set up import programs under which the exporting country agrees to produce plants for the U.S. market under a system of integrated pest risk management measures (IPRMM) approved by APHIS. In accordance with the international standards, the programs established under this new power will address how the place of production will manage pest risk and ensure traceability of plants; how APHIS and the exporting country will administer the program; how plant brokers will ensure plants remain pest-free while in their custody; how audits will be performed to ensure program efficacy; and what actions various parties will take in cases of noncompliance.

How efficacious this new approach will be in preventing new introductions will depend on how aggressive APHIS is in both choosing the plant taxa and places of-origin to be managed under such IPRMM programs and in negotiating the specific terms of the program with the exporting country.

It is discouraging that APHIS has ratcheted down how frequently it expects to rely on the IPRMM approach. In the explanatory material accompanying the final regulation, APHIS clarifies that did not intend that IPRMM would be used for all imports of living plants. The IPRMM framework is described as only one of several means to achieve the goal of preventing introduction of quarantine pests. APHIS will choose the “least restrictive measures” needed to prevent introduction of quarantine pests. To clarify its position, APHIS changed the introductory text to indicate that IPRMM will be applied when such measures are necessary to mitigate risk – that is, “when the pest risk associated with the importation of a type of plants for planting can only be addressed through use of integrated measures.” [Emphases added]

The final rule is also discouraging in some of its specifics.

- Whereas the draft regulation specified steps that places of production must take to ensure traceability of the plants they produce, in the final regulation the traceability elements specified in each IPRMM agreement will depend on the nature of the quarantine pests to be managed. Again, APHIS seeks to ensure that its requirements are not unnecessarily restrictive.

- Although the international standard had specified severe penalties when a grower or broker violated the terms of the IPRMM agreement, APHIS proposed to base the regulatory responses to program failures on existing bilateral agreements with the exporting country. Despite the Conservancy’s plea that APHIS follow ISPM#36 in adopting more specific and severe penalties, APHIS has not done so. The one bright spot is that APHIS may verify the efficacy of any remedial measures imposed by the phytosanitary agency of the exporting country to correct problems at the non-compliant place of production. [Emphasis added]

- APHIS is relaxing the detailed requirements for state post-entry quarantine agreements – despite the Conservancy’s concern that such agreements’ provisions could be influenced by political pressure and other nonscientific factors.

Two Improvements

I am pleased that APHIS has retained requirements applied to plant brokers, despite one commenter’s objections. Brokers handling international shipments of plants grown under an IPRMM program must both handle the plants themselves in ways that prevent infestation during shipment and maintain the integrity of documentation certifying the origin of the plants. A weakness, in my current view, is that APHIS will allow brokers to mix consignments of plants from more than one producer operating under the IPRMM program. APHIS does warn that if non-compliant (infested) plants are detected at import, all the producers whose plants were in the shipment would be subject to destruction, treatment, or re-export.

A major improvement under the new regulation is that APHIS will now operate under streamlined procedures when it wishes to amend the requirements for importing particular plants (whether a taxon, a “type”, or a country of origin). Until now, APHIS has been able to make such changes only through the cumbersome rulemaking process, Instead, APHIS will now issue a public notice, accept public comments, and then specify the new requirements through amendment of the “Plants for Planting Manual” [ https://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/Manuals/ports/downloads/plants_for_planting.pdf ] APHIS estimates that such changes can be finalized four months faster under the new procedure.

A Final Caveat

Finally, APHIS needs to be able to measure what effect the new procedures have on preventing pest introductions. Such measurement depends on a statistically sound monitoring scheme. APHIS has stated in some documents that the current Agriculture Quarantine Inspection Monitoring (AQIM) system doesn’t serve this purpose. APHIS needs to develop a valid monitoring program.

References

Haack RA, Britton KO, Brockerhoff EG, Cavey JF, Garrett LJ, et al. (2014) Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live Plant Imports: the Major Pathway for Forest Insect and Pathogen Invasions of the US. www.frontiersinecology.org

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

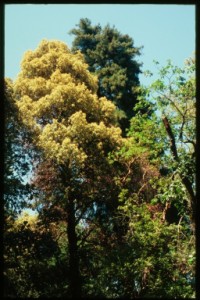

dogwood anthracnose

dogwood anthracnose

USDA; photo by F.T. Campbell

USDA; photo by F.T. Campbell

Customs inspecting wood packaging

Customs inspecting wood packaging