On May 19 I posted a blog asking you to lobby Congress in support of maintaining current funding levels for two programs aimed to eradicating or containing tree-killing pests. These are the “tree and wood pest” and “specialty crop” programs operated by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

At the time, I had not seen the President’s budget proposal. Now I have seen the President’s budget – and, as anticipated, it calls for steep cuts in the “tree and wood pest” program. The President calls for cutting this program by 44% — from $54 million to $30 million. Specifically, the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) eradication program would be cut by approximately 50% — $20.770. The emerald ash borer (EAB) containment program would also be cut by half — $3.127 million.

The President’s budget justifies these severe cuts by saying that states, localities, and industries benefit from eradication or containment of the ALB and EAB, so they should help pay for the containment program. The Office of Management and Budget states that other beneficiaries should pay 50% of program costs.

For whatever reason, the budget does not propose to cut APHIS’ efforts to prevent spread of the European gypsy moth.

In reality, states, localities, and industries are very unlikely to make up the difference in funding. We should remind the Congress that already, local governments across the country are spending more than $3 billion each year to remove trees on city property killed by non-native pests. Homeowners are spending $1 billion to remove and replace trees on their properties and are absorbing an additional $1.5 billion in reduced property values and reducing the quality of their neighborhoods. (See Aukema et al. article listed below.)

Cuts of the size proposed by the President’s budget will undermine the programs completely. Such a result is particularly alarming given the record of success in eradicating ALB populations – when resources are sufficient; and the urgent need to complete eradication programs in Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. As I said in May, the ALB program has succeeded in eradicating 85% of the infestation in New York. (APHIS has just announced that a section of the borough of Queens is free of ALB.) However, the infestation in Massachusetts has been only 34% eradicated; that in Ohio has been only 15% eradicated. Crippling the program now will expose urban and rural forests throughout the Northeast to severe damage by this insect, which attacks a wide range of species.

The importance of continuing the EAB containment program has been re-emphasized by scientists’ recent determination that EAB can attack commercial olive trees as well as all species of ash.

The budget also does not recognize the need for APHIS to expand its program to address other tree-killing pests, including the spotted lanternfly, and polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers.The shot hole borers attack hundreds of tree species, including California sycamore, cottonwoods, and several oaks. Many known hosts are either found across the Southeast, or belong to genera that are found across the Southeast – so the threat is national. The spotted lanternfly – now established in Pennsylvania — threatens agriculture – especially grapes, apples, plums, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots, and almonds; as well as oak, walnut, poplar, and pine trees.

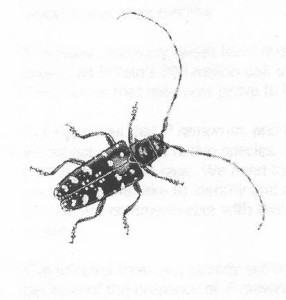

More than 30 tree-attacking pests have been introduced in recent years. Additional species from these introductions might also require APHIS-led programs; one example is the velvet longhorned beetle.

velvet longhorned beetle; bugwood.org

velvet longhorned beetle; bugwood.org

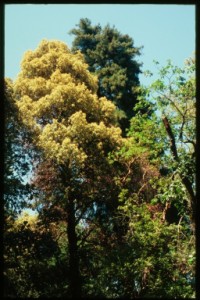

The budget calls also for a 6% cut on the “specialty crops” program – from $158 million to $148 million. It is not clear how such a reduction would affect APHIS’ program to prevent spread of the sudden oak death (SOD) via movement of nursery stock [link to earlier blogs & Gallery]. The SOD program has been funded at approximately $5 million in recent years.

Finally, additional challenges lie ahead because it is likely that new tree-killing pests will be introduced with rising import volumes. Each year, border inspectors detect more than 800 import shipments with pests infesting the crates and pallets. These represent a small proportion of the actual risk; one analysis estimated that 13,000 shipments with infested packaging enter the country each year. APHIS must have sufficient resources to respond when the inevitable newly introduced pests are detected.

Aukema, J.E., B. Leung, K. Kovacs, C. Chivers, K. O. Britton, J. Englin, S.J. Frankel, R. G. Haight, T. P. Holmes, A. Liebhold, D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle.. 2011. Economic Impacts of Non-Native Forest Insects in the Continental United States PLoS One September 2011 (Volume 6 Issue 9)

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.