I congratulate Australian scientists for bringing about substantial improvements of their country’s biosecurity program for forest pests. While it is too early to know how effective the changes will be in preventing new introductions, they are promising. What can we Americans learn from the Australian efforts? [I have previously praised South Africa’s efforts – there is much to learn there, too.]

Australia has a reputation of being very active in managing the invasive species threat. However, until recently biosecurity programs targetting forest pests were minimal and ad hoc. Scientists spent 30 years trying to close those gaps (Carnegie et al. 2022). Their efforts included publishing several reports or publications (listed at the end of the blog) and an international webinar on myrtle rust. Scientists are hopeful that the new early detection program (described below) will greatly enhance forest protection. However, thorough pest risk assessments are still not routinely conducted for forest pests. (Nahrung and Carnegie 2022).

The native flora of Australia is unique. That uniqueness has provided protection because fewer of the non-native insects and pathogens familiar to us in the Northern Hemisphere have found suitable hosts (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). Also – I would argue – the uniqueness of this flora imposes a special responsibility to protect it from threats that do arise.

Only 17% of Australia’s landmass is covered by forests. Australia is large, however; consequently, these forests cover 134 million hectares (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). This is the 7th largest forest estate in the world (Carnegie et al. 2022).

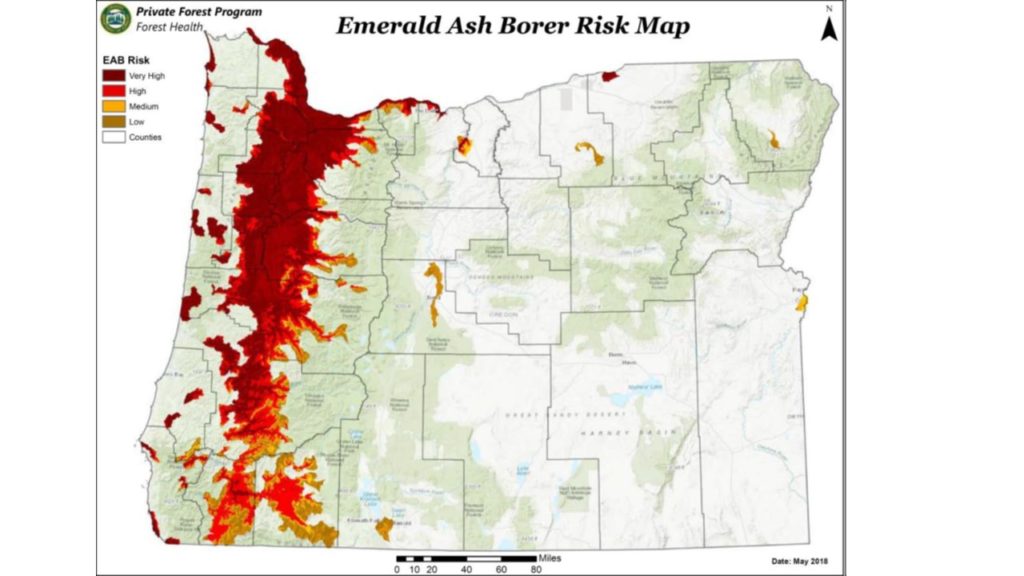

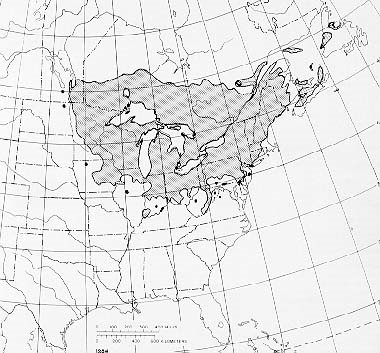

Australia’s forests are dominated by eucalypts (Eucalyptus, Corymbia and Angophora). These cover 101 million ha; or 75% of the forest). Acacia (11 million ha; 8%); and Melaleuca (6 million ha) are also significant. The forest also includes one million ha of plantations dominated by Pinus species native to North America (Carnegie et al. 2022). A wide range of native and exotic genera have been planted as amenity trees in urban and peri-urban areas, including pines, sycamores, poplars, oaks, and elms (Carnegie et al. 2022). These urban trees are highly valued for their ecosystem services as well as social, cultural, and property values (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). Of course, these exotic trees can support establishment and spread of the forest pest species familiar to us in the Northern Hemisphere. On the positive side, they can also be used as sentinel plantings for early detection of non-native species (Carnegie et al. 2022 and Nahrung and Carnegie 2020).

Despite Australia’s geographic isolation, its unique native flora, and what is widely considered to be one of the world’s most robust biosecurity system, at least 260 non-native arthropods and pathogens of forests have established in Australia since 1885 (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). [(This number is about half the number of non-native forest insects and pathogens that have established in the United States over a period just 25 years longer (Aukema et al. 2010).] As I noted, forest scientists have cited these introductions as a reason to strengthen Australia’s biosecurity system specifically as it applies to forest pests.

What steps have been taken to address this onslaught? For which pests? With what impacts? What gaps have been identified?

Which Pests?

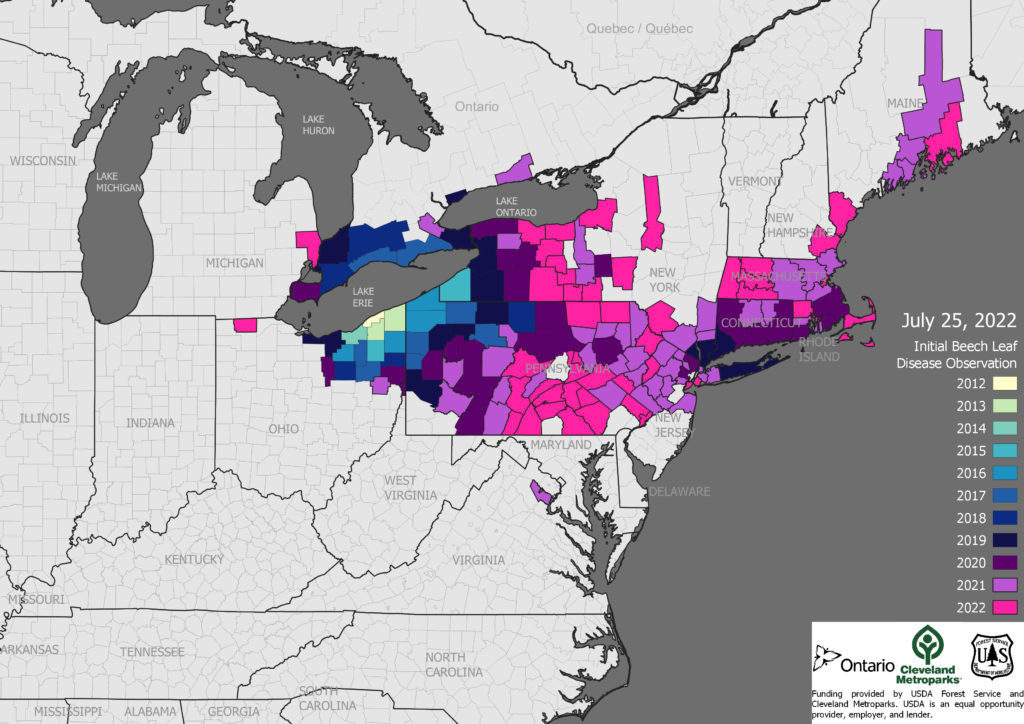

Nahrung and Carnegie (2020) compiled the first comprehensive database of tree and forest pests established in Australia. The 260 species of non-native forest insect pests and pathogens comprise 143 arthropods, 117 pathogens. Nineteen of them (17 insects and 2 fungal species) had been detected before 1900. These species have accumulated at an overall rate of 1.9 species per year; the rate of accumulation after 1955 is slightly higher than during the earlier period, but it has not grown at the exponential rate of import volumes.

While over the entire period insects and pathogens were detected at an almost equal rate (insects at 1.1/year; pathogens at 0.9/year), this disguises an interesting disparity: half of the arthropods were detected before 1940; half of the pathogens after 1960 (Nahrung and Carnegie (2020). By 2022, Nahrung and Carnegie (2022) said that, on average, one new forest insect is introduced each year. Some of these recently detected organisms have probably been established for years. More robust surveillance has just detected them recently. I have blogged often about an apparent explosion of pathogens being transported globally in recent decades.

In a more recent article (Nahrung and Carnegie, 2022), gave 135 as the number of non-native forest insect pests. The authors don’t explain why this differs from the 143 arthropods listed before.

Eighty-seven percent of the established alien arthropods are associated with non-native hosts (e.g., Pinus, Platanus, Populus, Quercus, Ulmus) (Carnegie et al. 2022). Some of these have escaped eradication attempts and caused financial impact to commercial plantations (e.g., sirex wood wasp, Sirex noctilio) and amenity forests (e.g., elm leaf beetle, Xanthogaleruca luteola) (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019).

About 40% of the alien arthropods were largely cosmopolitan at the time of their introduction in Australia (Carnegie et al. 2022). Only six insects and six fungal species are not recorded as invasive elsewhere (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). Of the species not yet established, 91% of interceptions from 2003 to- 2016 were known to be invasive elsewhere. There is strong evidence of the bridgehead effect: 95% of interceptions of three species were from their invaded range (Nahrung and Carnegie 2022). These included most of the insects detected in shipments from North America, Europe and New Zealand. These ubiquitous “superinvaders” have been circulating in trade for decades and continue to be intercepted at Australia’s borders. This situation suggests that higher interception rates of these species reflect their invasion success rather than predict it (Nahrung and Carnegie 2021).

I find it alarming that most species detected in shipments from Africa, South America, and New Zealand were of species not even recorded as established in those regions (Nahrung and Carnegie 2021; Nahrung and Carnegie 2022).

Half of the alien forest pests established in Australia are highly polyphagous. This includes 73% of Asian-origin pests but only 15% of those from Europe (Nahrung and Carnegie 2021). Nahrung and Carnegie (2022) confirm that polyphagous species are more likely to be detected during border inspections.

PATHWAYS

As in North America and Europe, introductions of Hemiptera are overwhelmingly (98%) associated with fresh plant material (e.g. nursery stock, fruit, foliage). Coleoptera introductions are predominantly (64%) associated with wood (e.g. packaging, timber, furniture, and artefacts). Both pathways are subject to strict regulations by Australia (Nahrung and Carnegie 2021).

Eradication of High-Priority Pests

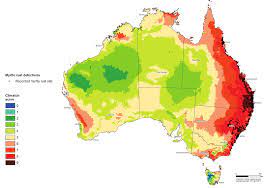

Eight-five percent of all new detections were not considered high-priority risks. Of the four that were, two had not previously been recognized as threats (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019). One high-priority pest – expected to pose a severe threat to at least some of Australia’s endemic plant species – is myrtle rust, Austropuccinia psidii. Despite this designation, when the rust appeared in Australia in 2010, the response was confused and ended in an early decision that eradication was impossible. Myrtle rust has now spread along the continent’s east coast, with localized distribution in Victoria, Tasmania, the Northern Territory, and – in 2022, Western Australia. `

There have been significant impacts to native plant communities. Several reviews of the emergency response criticized the haste with which the initial decision was made to end eradication (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019). (A review of these impacts is here; unfortunately, it is behind a paywall.)

A second newly introduced species has been recognized as a significant threat, but only after its introduction to offshore islands. This is Erythina gall wasp Quadrastichus erythrinae (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019). DMF Although Australia is home to at least one native species in the Erythrina genus, E. vespertilio,, the gall wasp is not included on the environmental pest watch list.

Four of the recently detected species were considered to be high impact. Therefore eradication was attempted. Unfortunately, these attempts failed in three cases. The single success involved a pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus hunanesis. See Nahrung and Carnegie (2021) for a discussion of the reasons. This means three species recognized as high-impact pests have established in Australia over 15 years (Nahrung and Carnegie (2021). In fact, Australia’s record of successful forest pest eradications is only half the global average (Carnegie and Nahrung (2019).

Carnegie and Nahrung (2019) conclude that improving early detection strategies is key to increasing the likelihood of eradication. They discuss the strengths and weaknesses of various strategies. Non-officials (citizen scientists) reported 59% of the 260 forest pests detected (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019). Few alien pests have been detected by official surveillance (Carnegie et al 2022). However, managing citizen scientists’ reports involves a significant workload. Futhermore, surveillance by industry, while appreciated, is likely to detect only established species (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019).

Interception Frequency Is Not an Indicator of Likelihood of Establishment

Nahrung & Carnegie (2021) document that taxonomic groups already established in Australia are rarely detected at the border. Furthermore, only two species were intercepted before they were discovered to be established in Australia.

Indeed, 76% of species established in Australia were either never or rarely intercepted at the border. While more Hemiptera species are established in Australia, significantly more species of Coleoptera are intercepted at the border. Among beetles, the most-intercepted family is Bostrichid borers (powderpost beetles). Over the period 2003 – 2016, Bostrichid beetles made up 82% of interceptions in wood packaging and 44% in wood products (Nahrung and Carnegie 2022). This beetle family is not considered a quarantine concern by either Australian or American phytosanitary officials. I believe USDA APHIS does not even bother recording detections of powderpost beetles. Nahrung and Carnegie (2021) think the high proportion of Bostrichids might be partially explained by intense inspection of baggage, mail, and personal effects. While Australia actively instructs travelers not to bring in fruits and vegetables because of the pest risk, there are fewer warnings about risks associated with wood products.

Nahrung & Carnegie (2021) concluded that interception frequencies did not provide a good overall indicator of likelihood of risk of contemporaneous establishment.

Do Programs Focus on the Right Species?

Although Hemiptera comprise about a third of recent detections and establishments, and four of eight established species are causing medium-to-high impact, no Hemiptera are currently listed as high priority forestry pests by Australian phytosanitary agencies (Nahrung & Carnegie (2021). On the other hand, Lepidoptera make up about a third of the high-priority species, yet only two have established in Australia over 130 years. Similarly, Cerambycidae are the most frequently intercepted forest pests and several are listed as high risk. But only three forest-related species have established (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020). (Note discussion of Bostrichidae above.).

Unlike the transcontinental exchanges under way in the Northern Hemisphere, none of the established beetles is from Asia; all are native to Europe. This is especially striking since interceptions from Asia-Pacific areas account for more than half of all interceptions Nahrung and Carnegie (2021).

Interestingly, 32 Australian Lepidopteran and eight Cerambycid species are considered pests in New Zealand. However, no forest pests native to New Zealand have established in Australia despite high levels of trade, geographic proximity, and the high number of shared exotic tree forest species (Nahrung and Carnegie 2020).

STRUCTURE OF PROGRAM

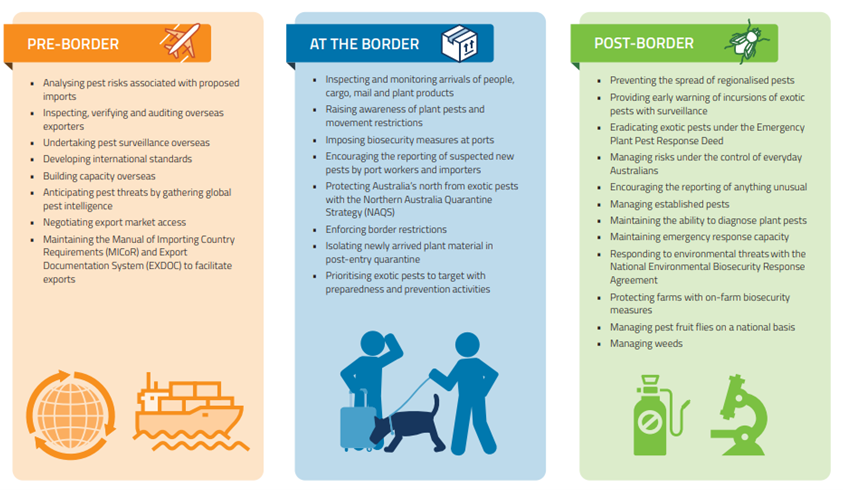

The structure of Australia’s plant biosecurity system is described in detail in Carnegie et al. (2022). These authors call the program “comprehensive” but to me it looks highly fragmented. The federal Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR,[recently renamed the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry, or DAFF) is responsible for pre-border (e.g., off-shore compliance) and border (e.g., import inspection) activities. The seven state governments, along with DAFF, are responsible for surveillance within the country, management of pest incursions, and regulation of pests. Once an alien pest has become established, its management becomes the responsibility of the land manager. In Australia, then, biosecurity is considered to be a responsibility shared between governments, industry and individuals.

Even this fragmented approach was developed more recently than one might expect given Australia’s reputation for having a stringent biosecurity system. Perhaps this reflects the earlier worldwide neglect of the Plant Kingdom? Carnegie and Nahrung (2019) describe recent improvements. Until the year 2000, Australia’s response to the detection of exotic plant pests was primarily case-by-case. In that year Plant Health Australia (PHA) was incorporated. Its purpose was to facilitate preparedness and response arrangements between governments and industry for plant pests. In 2005, the Emergency Plant Pest Response Deed (EPPRD) was created. It is a legally-binding agreement between the federal, state, and territorial governments and plant industry bodies. As of 2022, 38 were engaged. It sets up a process to implement management and funding of agreed responses to the detection of exotic plant pests – including cost-sharing and owner reimbursement. A national response plan (PLANTPLAN) provides management guidelines and outlines procedures, roles and responsibilities for all parties. A national committee (Consultative Committee on Emergency Plant Pests (CCEPP) works with surveys to determine invaded areas (delimitation surveys) and other data to determine whether eradicating the pest is technically feasible and has higher economic benefits than costs..

Even after creation of EPPRD in 2005, studies revealed significant gaps in Australia’s post-border forest biosecurity systems regarding forest pests (Carnegie et al. 2022; Carnegie and Nahrung 2019). These studies – and the disappointing response to the arrival of myrtle rust – led to development of the National Forest Biosecurity Surveillance Strategy (NFBSS) – published in 2018; accompanied by an Implementation Plan. A National Forest Biosecurity Coordinator was appointed.

The forest sector is funding a significant proportion of the proposed activities for the next five years; extension is probable. Drs. Carnegie and Nahrung are pleased that the national surveillance program has been established. It includes specific surveillance at high-risk sites and training of stakeholders who can be additional eyes on the ground. The Australian Forest Products Association has appointed a biosecurity manager (pers. comm.)

This mechanism is expected to ensure that current and future needs of the plant biosecurity system can be mutually agreed on, issues identified, and solutions found. Plant Health Australia’s independence and impartiality allow the company to put the interests of the plant biosecurity system first. It also supports a longer-term perspective (Carnegie et al. (2022). Leading natural resource management organizations are also engaged (Carnegie, pers. comm.).

Presumably the forest surveillance strategy (NFBSS) structure is intended to address the following problems (Carnegie and Nahrung 2019):

- Alien forest pests are monitored offshore and at the border, but post-border surveillance is less structured and poorly resourced. Australia still lacks a surveillance strategy for environmental pests.

- Several plant industries have developed their own biosecurity programs, co-funded by the government. These include the National Forest Biosecurity Surveillance Strategy (NFBSS).

Some pilot projects targetting high risk sites were initiated in the early 2000s. By 2019, only one surveillance program remained — trapping for Asian spongy (gypsy) moth.

- The states of Victoria and New South Wales have set up sentinel site programs. Victoria’s uses local council tree databases. It is apparently focused on urban trees and is primarily pest-specific – e.g., Dutch elm disease. The New South Wales program monitors more than 1,500 sentinel trees and traps insects near ports. This program is funded by a single forest grower through 2022.

Dr. Carnegie states: “With the start of the national forest biosecurity surveillance program in December 2022, the issues and gaps identified by Carnegie et al. 2022 are starting to be addressed. The program will conduct biosecurity surveillance specifically for forest pests and pathogens and be integrated with national and state biosecurity activities. While biosecurity in Australia is still agri-centric, a concerted and sustained effort from technical experts from the forest industry is changing this. And finally, the new Biosecurity Levy should ensure sustained funding for biosecurity surveillance.”

There is a separate National Environmental Biosecurity Response Agreement (NEBRA), adopted in 2012. It is intended to provide guidelines for responding, cost-sharing arrangements, etc. when the alien pest threatens predominantly the environment or public amenity assets (Carnegie et al. (2022). However, when the polyphagous shot hole borer was detected, the system didn’t work as might have been expected. While PSHB had previously been identified as an environmental priority pest, specifically to Acacia, the decision whether to engage was made under auspices of the the Emergency Plant Pest Response Deed (EPPRD) rather than the environmental agreement (NEBRA). As a result, stakeholders focused on environmental, amenity and indigenous concerns had no formal representation in decision-making processes; instead, industries that had assessed the species as a low priority (e.g., avocado and plantation forestry) did (Nahrung, pers.comm.).

Additional Issues Needing Attention

Some needs are not addressed by the National Forest Pest Strategic Plan (Carnegie et al. 2022) (Nahrung, pers. comm.):

1) The long-term strategic investment from the commercial forestry sector and government needed to maintain surveillance and diagnostic expertise;

2) Studies to assess social acceptance of response and eradication activities such as tree removal;

3) Studies to improve pest risk prioritization and assessment methods; and

4) Resolving the biosecurity responsibilities for pests of timber that has been cut and used in construction.

In 2019, Carnegie and Nahrung (2019) called for developing more effective methods of detection, especially of Hemiptera and pathogens. They also promoted national standardization of data collection. Finally, they advocated inclusion of technical experts from state governments, research organizations and industry in developing and implementing responses to pest incursions. They note that surveillance and management programs must be prepared to expect and respond to the unexpected since 85% of the pests detected over the last 20 years—and 75% of subsequently mid-to high-impact species established—were not on high-priority pest list. See Nahrung and Carnegie 2022 for a thorough discussion of the usefulness and weaknesses of predictive pest listing.

SOURCES

Aukema, J.E., D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle, A.M. Liebhold, K. Britton, & S.J. Frankel. 2010. Historical Accumulation of Nonindigenous Forest Pests in the Continental United States. Bioscience. December 2010 / Vol. 60 No. 11

Carnegie A.J. and H.F. Nahrung. 2019. Post-Border Forest Biosecurity in AU: Response to Recent Exotic Detections, Current Surveillance and Ongoing Needs. Forests 2019, 10, 336; doi:10.3390/f10040336 www.mdpi.com/journal/forests

Carnegie A.J., F. Tovar, S. Collins, S.A. Lawson, and H.F. Nahrung. 2022. A Coordinated, Risk-Based, National Forest Biosecurity Surveillance Program for AU Forests. Front. For. Glob. Change 4:756885. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2021.756885

Nahrung H.F. and A.J. Carnegie. 2020. NIS Forest Insects and Pathogens in Australia: Establishmebt, Spread, and Impact. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 3:37. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2020.00037 March 2020 | Volume 3 | Article 37

Nahrung, H.F. and A.J. Carnegie. 2021. Border interceps of forest insects estab in AU: intercepted invaders travel early and often. NeoBiota 64: 69–86. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.64.60424

Nahrung, H.F. & A.J. Carnegie. 2022. Predicting Forest Pest Threats in Australia: Are Risk Lists Worth the Paper they’re Written on? Global Biosecurity, 2022; 4(1).

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or