Every five years, Congress adopts a new Farm Bill. The House and Senate Agriculture committees are holding hearings and considering proposals for the Farm Bill due to be adopted in 2019. Now is the time for people concerned about the continuing introductions of forest pests and weakness of our government’s response to pests that have become established to ask their Representative and Senators to adopt legislative language to strengthen relevant USDA programs. I suggest specific proposals below – which I hope you will urge your representatives to support.

The Farm Bill supports our Nation’s largest soil and water conservation programs. The Farm Bill can also be used to create new programs that address other issues – such as pest prevention and response.

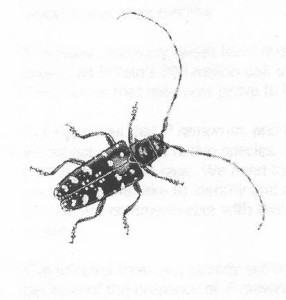

The Farm Bill already has been used to strengthen APHIS’ phytosanitary programs. For example, Section 10007 of the 2014 Farm Bill provides more than $50 million annually for the Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Prevention Program. These funds have supported numerous vitally important research and management programs targetting polyphagous shot hole borer, spotted lanternfly, velvet longhorned borer, thousand cankers disease, emerald ash borer, as well as more general goals such as improving traps for detecting wood-borers and outreach about emerald ash borer to Native American tribes. With APHIS’ annual appropriations falling far short of the resources needed to respond to invasions by numerous plant pests, Section 10007 has provided essential supplements to the agency’s programs.

The new Farm Bill to be adopted by the Congress offers opportunities to strengthen other components of USDA programs with the goal of protecting the tree species comprising our wildland, rural, and urban forests.

The Center for Invasive Species Prevention and Vermont Woodland Owners Association have developed several proposals that we hope will be incorporated into the 2019 Farm Bill. These proposals have been endorsed by the Reduce Risk from Invasive Species Coalition. The amendments have also been endorsed by the Weed Science Society of America. CISP submitted testimony summarizing these proposals to the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry in early July, when the Committee held a hearing on the Farm Bill’s conservation and forestry programs. (For a copy of our testimony, contact us using the “contact us” button.)

You can help by contacting your Representative and Senators and asking them to support these proposed amendments to the 2019 Farm Bill.

These proposed amendments seek to address the following needs.

- Do you wish to strengthen APHIS’ commitment to pest prevention in the face of a competing mandate to facilitate trade?

Then you might want to support a proposed amendment to Section 3 of the Plant Protection Act. The new language would read as follows:

“(3) It is the responsibility of the Secretary to facilitate exports, imports and interstate commerce in agricultural products and other commodities that pose a risk of harboring plant pests or noxious weeds in ways that will reduce prevent, to the greatest extent practicable feasible, as determined by the Secretary, the risk of dissemination of plant pests and noxious weeds.”

- Do you wish to increase funding for APHIS’ programs responding to recently-detected plant pests?

Then you might want to support a proposed amendment that would expand APHIS’ access to emergency funds by enacting a broad definition of “emergency”. Under the new definition, “emergency” would mean “any outbreak of a plant pest or noxious weed which directly or indirectly threatens any segment of the agricultural production of the United States and for which the then available appropriated funds are determined by the Secretary to be insufficient to timely achieve the arrest, control, eradication, or prevention of the spread of such plant pest or noxious weed.”

This amendment would help APHIS evade the downward push of its declining annual appropriation and enable the agency to tackle more of the tree-killing pest that have entered the U.S.

Customs inspecting wood packaging

Customs inspecting wood packaging

- Do you wish to promote stronger measures aimed at minimizing the presence of pests in wood packaging material? (I have blogged repeatedly about the continuing pest risk associated with the wood packaging pathway.)

Then you might want to support a proposed amendment that would establish a non-governmental Center for Agriculture-Trade Partnership Against Invasive Species. That Center would promote industry best practices, encourage information-sharing, and create an industry certification program under which importers would voluntarily implement pest-prevention actions that are more stringent than current regulations (ISPM#15) Link require.

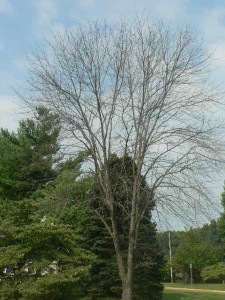

American Chestnut Foundation chestnut in experimental planting in Fairfax County, Virginia; photo F.T. Campbell

- Do you wish to strengthen efforts to develop programs that would provide long-term funding to support 1) research and development of long-term pest-control strategies such as biological control and breeding of trees resistant to insects or pathogens and 2) testing, development, and implementation of strategies to restore to the forest native tree species that have been severely depleted by non-native pests?

Then you might want to support a pair of proposed amendments that would:

- Establish a fund, to be managed by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, to provide grants under which eligible institutions would carry out research intended to test and develop strategies aimed at restoring such tree species. Such strategies might include finding, testing, and deploying biological control agents or breeding of trees resistant to pests.

- Amend the McIntyre-Stennis Act to establish a fund to provide grants to support programs to eligible institutions to conduct experimental plantings aimed at restoring such tree species to the forest.

You can obtain copies of the proposed amendments, in legislative language, by contacting us using the “contact us” button.

Your efforts will be valuable in any case … but if your Representative or Senator is on the agriculture committee, contacting that Member will be most important!

Members of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry:

Republicans (majority):

- Pat Roberts, KS, Chairman

- Thad Cochran, MS

- Mitch McConnell, KY

- John Boozman, AR

- John Hoeven, ND

- Joni Ernst, IA.

- Chuck Grassley, IA

- John Thune, SD.

- Steve Daines, MT

- David Perdue, GA

- Luther Strange, AL

Democrats (minority):

- Debbie Stabenow, MI, Ranking Member

- Patrick Leahy, VT

- Sherrod Brown, OH

- Amy Klobuchar, MN

- Michael Bennet, CO

- Kirsten Gillibrand, NY

- Joe Donnelly, IN

- Heidi Heitkamp, ND

- Bob Casey Jr., PA

- Chris Van Hollen, MD

Members of the House Committee on Agriculture

Republicans (majority):

- K. Michael Conaway, TX, Chairman

- Glenn ‘GT’ Thompson, PA, Vice Chairman

- Bob Goodlatte, VA

- Frank D. Lucas, OK

- Steve King, IA

- Mike Rogers, AL

- Bob Gibbs, OH

- Austin Scott, GA

- Rick Crawford, AR

- Scott Desjarlais, TN

- Vicky Hartzler, MO

- Jeff Denham, CA

- Doug LaMalfa, CA

- Rodney Davis, IL

- Ted Yoho, FL

- Rick Allen, GA

- Mike Bost, IL

- David Rouzer, NC

- Ralph Abraham, LA

- Trent Kelly, MS

- James Comer, KY

- Roger Marshall, KS

- Don Bacon, NE

- John Faso, NY

- Neal Dunn, FL

- Jodey Arrington, TX

Democrats (minority):

- Collin C. Peterson, MN, Ranking Member

- David Scott, GA

- Jim Costa, CA

- Timothy J. Walz, MN

- Marcia Fudge, OH

- Jim McGovern, MA

- Filemon Vela, TX

- Michelle Lujan Grisham, NM

- Ann Kuster, NH

- Rick Nolan, MN

- Cheri Bustos, IL

- Sean Patrick Maloney, NY

- Stacey Plaskett, VI

- Alma Adams, NC

- Dwight Evans, PA

- Al Lawson, FL

- Tom O’Halleran, AR

- Jimmy Panetta, CA

- Darren Soto, FL

- Lisa Blunt Rochester, DE

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Posted by Faith Campbell

USDA; photo by F.T. Campbell

USDA; photo by F.T. Campbell