CBP inspecting wood packaging; CBP photo

CBP inspecting wood packaging; CBP photo

There is widespread agreement that the most important pathways for long-distance transport of non-native forest insects are wood packaging (crates, pallets, dunnage, etc.) and imports of live plants (which APHIS calls “plants for planting”). Sources (at end of blog): Aukema et al. 2010; Liebhold et al. 2012; Meurisse et al. 2018 and many others. See also my earlier blogs by scrolling down to the “categories” section and clicking on “wood packaging”.

According to Meurisse et al., by the middle of this decade, world maritime freight trade had reached about 10 billion metric tonnes, and air transport of cargo had reached 50 million tonnes – much of it packaged in wood.

As the world’s biggest importer, the United States receives about 27 million shipping containers each year (CBP to FT Campbell). A study carried out in 2005 – 2007 (Meissner et al. 2009) indicated that 75% of maritime shipments entering the U.S. contained wood packaging; 33% of air shipments contained wood packaging. These are significant increases over earlier estimates that put the number of containers entering the country at 25 million. An even older analysis estimated that 52% of incoming containers had wood packaging.

APHIS has recognized the pest risk associated with wood packaging for 20 years – since the Asian longhorned beetle was detected in a second city – Chicago – in 1998. APHIS and its Canadian counterpart (Canadian Food Inspection Agency) acted rapidly to adopt, first, domestic regulations governing wood packaging from China (in December 1998), then a regional standard for wood packaging, and finally to help bring about adoption of International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) No. 15 in 2002. A detailed description of these actions can be found in my report Fading Forests II available here.

However, as I have demonstrated often, ISPM#15 has reduced the threat – but insufficiently. Dr. Robert Haack and his coauthors (2014) found that of each thousand shipments containing wood packaging that enters the country, one harbors a quarantine pest. Applying this estimate to the current volume of incoming containers and the higher proportion containing wood packaging results in an estimate that up to 20,000 shipping containers containing infested wood packaging enter the country each year – or approximately 55 per day.

The actual approach rate might be less. There are two variables that I lack sufficient data to quantify.

First, a significant proportion of the incoming containers come from Mexico or Canada – our second and third largest trading partners. The risk of damaging pests arriving from our neighbors is less than the risk accompanying shipments from overseas – although it is not “0”. Several woodborers native to Mexico have been introduced to U.S. ecosystems and are killing trees in these new environments, e.g., goldspotted oak borer, walnut twig beetle, and soapberry borer (all described in write-ups here). It is true that these beetles were probably introduced to vulnerable parts of the U.S. in firewood rather than wood packaging. There are also reasons to be concerned about pest introductions from Canada. Threats arise from both non-native pests established in the country e.g., brown spruce longhorned beetle and European beech leaf weevil, and pests in shipments from off-shore origins that are re-packaged in Canada (Yemshanov et al. 2012 and my earlier blog from April 2017).

The second variable on which I lack data is the proportion of the 27 million containers that are transported by air, and are thus half as likely to contain wood packaging.

To account for these unknowns, I have nearly halved the number of shipping containers likely to transport pests from off-shore – so 14 million instead of 27 million. Again applying Haack’s estimate, the result is 10,500 shipping containers containing infested wood packaging entering the country every year – or approximately 29 every day.

Update with more precise data (August 24) :

Re: the two variables, I have found partial answers from a U.S. Department of Transportation website which provides data on imports of loaded chipping containers (in TEUs) for 68 ports. (For the website, go here – click on “trade statistics”, then “US Waterborne trade” (1st bullet)]

As of 2017, 22,360,941 loaded shipping containers entered the U.S. via maritime transport. Applying the estimate of 75% of these containers holding wood packaging, we find that slightly less than 17 million containers entered the country with wood packaging. Applying Robert Haack’s estimate that one in a thousand is infested with a quarantine insect, we anticipate that 17,000 of these containers were transporting a pest that threatens our country. That is 46 containers every day.

Ports which received the largest numbers of containers, according to the DoT database:

- Long Beach/Los Angeles — 8.4 million containers

- New York — 3.4 million containers

- Savannah — 1.8

- Norfolk — 1.2

- Houston — 1 million containers

We need answers!

The point is, we don’t know how many pests are reaching the United States daily. Or if the current approach rate is significantly higher or lower than in the past. Despite my urging, APHIS has not undertaken a study to update Haack’s estimate – which is based on 2009 data. In the intervening nine years, several changes were made to ISPM#15 to make it more effective. The most important was restricting the size of bark remnants that may remain on the wood.

Also, we might hope that experience with implementing the standard has led to better compliance. Unfortunately, available data do not encourage belief that compliance has improved.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reports annually to the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases on the number of import shipments with wood packaging that have been detected as not complying with ISPM#15. Over a period of eight years – Fiscal years 2010 through 2017 – CBP detected nearly 24,000 non-compliant shipments. While most (17,413) of the non-compliances were crates or pallets that lacked the required mark showing treatment in accordance with ISPM#15, in 6,388 cases the wood packaging actually harbored a pest in a regulated taxonomic group. This works out to about 800 infested shipments detected each year.

By comparing Dr. Haack’s estimate with the CBP data, I estimate that Customs is detecting and halting the importation of four to eight percent of the shipments that actually contain pest-infested wood. Since CBP inspects only about two percent of incoming shipments, this detection rate demonstrates the value of CBP’s program to target likely violators – and deserves praise. But it is obviously too low a “catch” rate to provide an adequate level of protection for our forests.

Indeed, using the older, lower estimates of both numbers of shipping containers and the proportion that contain wood packaging, Leung et al. 2014 concluded that continuing to implement ISPM#15 at the efficacy level described by Haack et al. would result in a tripling of the number of non-native wood-boring insects introduced into the U.S. by 2050.

Closer examination of the data raises more troubling questions. On average, 97% of the 6,388 shipments containing infested wood pieces detected by CBP were found in wood that bore the ISPM#15 stamp indicating that it had been treated. The proportion of infested shipments bearing the stamp has not changed over the past eight years. This is alarming and we need to understand the reason. Does this finding indicate widespread fraud? I understand that most inspectors believe this is the cause. Other possible explanations are accidental misapplication of the treatments or the treatments simply not working as expected. APHIS researchers have found that larvae from wood subjected to methyl bromide fumigation were more likely to survive to adulthood than those intercepted in wood that had been heat treated (Nadel et al. 2016). Does this indicate that methyl bromide fumigation is less effective? What effort is APHIS making to determine which of these explanations is correct?

Certain countries have a long-standing record of non-compliance with ISPM#15. APHIS’ database of pest interceptions on wood packaging over the period Fiscal Year 2011 to FY 2016 contains 2,547 records of insect detections from dozens of countries. The countries of origin with the highest numbers of shipments detected to have pests present were Mexico, China, Italy, and Costa Rica. These numbers reflect in part the huge volumes of goods imported from both Mexico and China. But China and Italy stand out for their poor performance. (The U.S. does not regulate – or inspect! – wood packaging from Canada; see blog here.)

Meissner et al. say that as of a decade ago, Chinese shipments were only half as likely to be enclosed in wood packaging as are shipments from other exporters. Yet shipments from China still rank second in the number of non-compliant shipments; they make up 11% of all interceptions. In part, the data reflect inspection priorities: due to the great damage caused by Asian insects to North American trees and the past record of poor compliance, CBP targets shipments from China for more intense scrutiny. Still, the high number of detections reflects continuing non-compliance by Chinese exporters. And remember – the U.S. and Canada began requiring treatment of wood packaging from China at the end of 1998 – nearly 20 years ago! [Feb 17 blog]

shipment of decorative stone with wood packaging

shipment of decorative stone with wood packaging

We don’t import a lot of goods from Italy – but Italian shipments of decorative stone and tile have always been plagued by high levels of pests in accompanying wood packaging. Indeed, more pests have been found in wood supporting tiles and stone than any other type of commodity in 24 of the 25 years preceding 2014 (Haack et al. 2014).

What is APHIS doing to pressure these countries to improve their compliance? As I blogged in October, link the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection began imposing a financial penalty on first-time violators in November 2017. Since interception data do not provide an adequate measure of the pest approach rate (see Haack et al 2014 for an explanation), APHIS should commission an analysis of Agriculture Quarantine Inspection Monitoring data to determine the pest approach rate before and after the CBP action in order to determine whether the more aggressive enforcement has led to reductions in non-compliant shipments at the border.

What Can Be Done to Slow or Eliminate this Pathway?

I reiterate my call for holding foreign suppliers responsible for complying with ISPM#15. One approach is to penalize violators. Now that the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection has toughened its enforcement, the U.S. Department of Agriculture should drop its decade-old policy of allowing importers to accumulate five (detected) violations in a calendar year before applying the civil penalties authorized by the Plant Protection Act.

Another step APHIS should take would be to prohibit use of packaging made from solid wood (boards, 4 x 4s, etc.) by foreign suppliers which have a record of repeated violations over the 12 years that ISPM#15 has been in effect – or the 19 + years for exporters from Hong Kong & mainland China. Officials should allow continued imports from those same suppliers as long as they are contained in other types of packaging materials, including plastic, metals, fiberboards …

SOURCES

Aukema, J.E., D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle, A.M. Liebhold, K. Britton, & S.J. Frankel. 2010. Historical Accumulation of Nonindigenous Forest Pests in the Continental United States. Bioscience. December 2010 / Vol. 60 No. 11

Haack, R. A., K. O. Britton, E. G. Brockerhoff, J. F. Cavey, L. J. Garrett, M. Kimberley, F. Lowenstein, A. Nuding, L. J. Olson, J. Turner, and K. N. Vasilaky. 2014. Effectiveness of the international phytosanitary standard ISPM no. 15 on reducing wood borer infestation rates in wood packaging material entering the United States. Plos One 9:e96611.

Hulme, P.E. 2009. Trade, transport and trouble: Managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. Journal of Applied Ecology 46:10-18

Jung, T. et al. 2015 “Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora disease” Forest Pathology. November 2015; available from Resource Gate

Klapwijk, M.J., A.J. M. Hopkins, L. Eriksson, M. Pettersson, M. Schroeder, A. Lindelo¨w, J. Ro¨nnberg, E.C.H. Keskitalo, M. Kenis. 2016. Reducing the risk of invasive forest pests and pathogens: Combining legislation, targeted management and public awareness. Ambio 2016, 45(Suppl. 2):S223–S234 DOI 10.1007/s13280-015-0748-3

Koch, F.H., D. Yemshanov, M. Colunga-Garcia, R.D. Magarey, W.D. Smith. 2011. Potential establishment of alien-invasive forest insect species in the United States: where and how many? Biol Invasions (2011) 13:969–985

Leung, B., M.R. Springborn, J.A. Turner, E.G. Brockerhoff. 2014. Pathway-level risk analysis: the net present value of an invasive species policy in the US. The Ecological Society of America. Frontiers of Ecology.org

Levinson, M. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger Princeton University Press 2008

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live Plant Imports: the Major Pathway for Forest Insect and Pathogen Invasions of the US. www.frontiersinecology.org

Meissner, H., A. Lemay, C. Bertone, K. Schwartzburg, L. Ferguson, L. Newton. 2009. Evaluation of Pathways for Exotic Plant Pest Movement into and within the Greater Caribbean Region. Caribbean Invasive Species Working Group (CISWG) and USDA APHIS Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory

Meurisse, N. D. Rassaati, B.P. Hurley, E.G. Brockerhoff, R.A. Haack. 2018. Common Pathways by which NIS forest insects move internationally and domestically. Journal of Pest Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-0990-0

Nadel, H., S. Myers, J. Molongoski, Y. Wu, S. Linafelter, A. Ray, S. Krishnankutty, A. 2016. Identificantion of Port Interceptions in Wood Packaging Material Cumulative Progress Report, April 2012 – August 2016

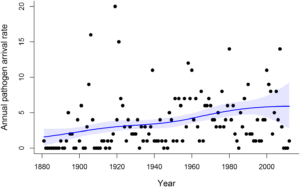

Sikes, B.A., J.L. Bufford, P.E. Hulme, J.A. Cooper, P.R. Johnston, R.P. Duncan. 2018. Import volumes and biosecurity interventions shape the arrival rate of fungal pathogens. http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2006025

Yemshanov, D., F.H. Koch, M. Ducey, K. Koehler. 2012. Trade-associated pathways of alien forest insect entries in Canada. Biol Invasions (2012) 14:797–812

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

California red-legged frog

California red-legged frog

dogwood anthracnose

dogwood anthracnose