rhododendron in Europe sickened by P. ramorum; photo from EPPO website

A recently published study by European researchers [Jung, T. et al. 2015] documents the failure of current European and global phytosanitary programs and calls for “a new holistic and integrated systems approach”. The authors specifically criticize Article VI.2 of the International Plant Protection Convention because it requires that a plant pest be identified and its risks assessed before a country may adopt a phytosanitary measures. The authors call this requirement “paradoxical” given the large number of potentially damaging plant pests that remain unknown to science.

The study focuses on the genus Phytophthora, which contains about 150 identified species and perhaps 500 species not yet identified by scientists. The identified species include plant pathogens which are responsible for more than 66% of all fine root diseases & more than 90% of all collar rots of woody plant species. Examples include the pathogens responsible for the Irish potato famine, sudden oak death, Port-Orford-cedar root disease, the die-off of many endemic plant species in Western Australia and damage to many other species in Europe and North America, and mortality and decline of oaks and alders across Europe.

The authors note that

- Most of the ~150 currently known species and designated taxa of Phytophthora were unknown to science before they turned up in new environments on other continents as invasive aggressive pathogens of native plants.

- Forty-four of the 64 Phytophthora taxa detected in the present study were unknown to science before 1990.

- None of the 59 putatively exotic Phytophthora taxa detected in the present study had been intercepted at European ports of entry. (Some of these introductions are known to be recent; see UK reports on the 4th P. ramorum lineage ) and P. lawsonii detections in the U.K., France and the Netherlands in 2010.)

- In many cases, had a Phytophthora been detected, the detection would not have resulted in rejection of the shipment because only 5 Phytophthora species are regulated under European regulations.

- Spread of the quarantine organism ramorum was not halted despite the presence of strict quarantine regulations.

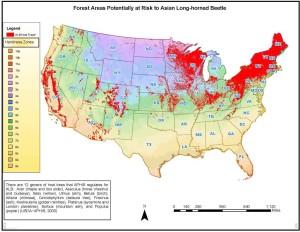

I have written several times about the threat to U.S. trees and forests from insects and – especially – pathogens introduced via the trade in live plants; see Fading Forests II and III . Fading Forests II discusses the threat from unknown pests and the roadblocks to managing that threat raised by the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and the implementing procedures adopted by the International Plant Protection Convention. Fading Forests III discusses USDA APHIS efforts to adopt more effective regulatory approaches through adoption of both international and regional standards (ISPM#36 and RSPM#24) and revision of its own Q-37 regulations.

Jung and his 65 (!) coauthors present some frightening facts about the situation in European nurseries and forest, landscape, and ornamental plantings:

- They found a total of 68 Phytophthora taxa (species, informally designated taxa, and previously unknown taxa). 49 taxa were found in nurseries, 56 in forest and landscape plantings.

- 91% of the 732 nurseries analyzed had at least 1 Phytophthora taxon present; in the 101 infested nurseries in which more than 5 stands were tested, an average of 3.6 Phytophthora taxa per nursery were detected

- 66% of forest & landscape plantings had at least 1 Phytophthora taxon present

- The majority of infested plants in nurseries did not display symptoms; the sampling methods for plantings relied to a large extent on symptoms, so the presence of symptomless plants could not be evaluated.

- Hundreds of previously unknown Phytophthora–host associations were observed.

- One or more of 19 Phytophthora which can attack native European or widely-planted trees and shubs were isolated from 84% of ornamental planted stands. Two such pathogens were detected in 11.8% of those stands.

- In a single British ornamental and amenity planting, 15 different Phytophthora taxa were isolated from 33 different species and varieties of plants. Smaller numbers were isolated from smaller numbers of sampled plants in other countries.

- The infestation rate for various types of plantings ranged from 94% for riparian plantings through 83.1% for horticultural plantings to 79.3% for forest plantings. About half of amenity and ornamental plantings had one or more infestations.

- 64% of oak plantings were infested by at least one Phytophthora species associated with decline of mature oak stands. Eight of the 9 plantings of Laurus nobilis in Spain and the UK hosted Phytophthora. Rates varied for other types of trees.

- In total, 755 ornamental plantings of 281 broadleaved woody and herbaceous species were sampled in 8 countries. 45% had at least one of the 21 Phytophthora taxa known to damage a wide range of European and widely planted exotic tree and shrub species. About 10% of the tested stands had more than one.

As the authors state, their results clearly demonstrate that the vast preponderance of nursery stands across Europe are infested by a large array of Phytophthora species. Nurseries and other plantings relied on as sources of plants for afforestation and other outplantings are routinely infected by the most aggressive Phytophthora pathogens that attack the respective tree or crop species. The result is continuous high-frequency spread of these aggressive pathogens to planted forests and horticultural systems — and will inevitably result in their introduction to the wider environment.

They estimate that 4.8 million ha of the 6 million ha of new forests planted in Europe over the past 20 years are potentially infested by Phytophthora pathogens. Another 17.6 million ha of forests replanted after harvesting or fire were possibly established with Phytophthora-infested nursery stock.

Why has this happened? The authors note that under current nursery growing practices, individual plants often flow largely unregulated through several nurseries both within and between countries before being sold to a consumer. In addition, such common nursery practices as reusing containers, irrigating with unfiltered surface water or recirculated water, poor drainage and failure to remove dead plants and debris all contribute to establishment and spread of Phythothora. These same criticisms have been made by U.S. scientists – and incorporated into APHIS’ revised regulations for management of sudden oak death and the nursery-regulatory SANC program now being tested.

Is the situation equally bad in North America? Jung et al. cite several publications that cumulatively demonstrate high infestation rates of U.S. ornamental nurseries with at least 31 Phytophthora species. They say that the situation in forest nurseries is largely unknown.

Certainly both continents are at high risk of additional introductions. U.S. plant imports reached 3.2 billion in 2007 (Liebhold et al. 2012). I am unaware of a more recent calculation … In 2010, ten European countries cumulatively imported 4.3 billion living plants from overseas; almost all were imported first to the Netherlands. The principal source was Africa (3.6 billion). Asia shipped 456 million plants; North America 181 million; South America 81 million; Oceania only 2.4 million plants. Between 2007 and 2010, the volume of imported woody plants increased by 44%, and in 2010, the proportion of woody plants reached 20.8% of all imported plants. Only 3% of the imported consignments are subject to phytosanitary inspections.

As Jung et al. note, their study joins an ever-longer list of analyses that have concluded that current international plant health protocols based on random visual inspections for symptoms of listed quarantine organisms have failed and must be changed fundamentally. (See, for example, the writing of Clive Brasier and the Montesclaros Declaration.

Jung et al. call for adoption of a pathway regulation approach based on pathway risk analyses, and risk-based inspection regimes performed by an adequate number of skilled staff using molecular high-throughput detection tools. Nurseries wishing to ship plants internationally would have to comply with mandatory best practices. The requirements must be supported by rigorous enforcement and bold outreach campaigns. This approach would minimize the risks of further introductions and dissemination of both known and, even more importantly, unknown potential pathogens.

MY CONCLUSION

Revising the international phytosanitary regime will be difficult, requiring 170 countries to agree to amend both the World Trade Organization’s SPS Agreement and the International Plant Protection Convention. The difficulties will be not only political. Allowing countries to regulate unknown organisms that are potential pests will open a door to protectionist restrictions. The countries that wrote these agreements have long sought to block protectionist restrictions by requiring that phytosanitary measures be based on scientific analyses of specific risks.

However, as Jung et al. – and before them many others, especially Clive Brasier – have demonstrated, the current requirement that each pathogen be identified and its risk analyzed before regulations are adopted is counter to the scientific fact that most pathogens and arthropods are not known to science. The knowledge gap is many times greater when the question is how those microorganisms and arthropods will interact with millions of plant species if introduced to novel habitats.

Meanwhile, USDA APHIS has begun trying to close some of the regulatory gaps. In 2011 APHIS adopted regulations creating a temporary holding category, called “Not Authorized (for importation) Pending Pest Risk Analysis,” or NAPPRA. Now, APHIS has authority to temporarily prohibit import of certain types of plants, from specific countries of origin, that it considers to pose a particular pest risk. The temporary ban gives APHIS time to complete a pest risk analysis and then enact appropriate safeguards to ensure that imported plants will be as pest-free as possible. However, APHIS has been unable to utilize this new power. The agency proposed a second round of “NAPPRA” species in May 2013, but nearly 3 years later it has not finalized that action. Even if fully implemented, NAPPRA does not address the problem of unknown pests and pathogens.

APHIS has also proposed a major revision of its plant import regulations (called “Q-37”). This change would implement the IPPC standard on living plants (ISPM#36) and authorize APHIS to require foreign suppliers of plants to apply hazard identification and mitigation practices to ensure plants are pest-free. APHIS proposed this rule change 3 years ago, in 2013. Again, the change has not yet been finalized.

What You Can Do

Write to your member of Congress and Senators and ask them to urge the Secretary of Agriculture to finalize the two pending regulations – to add the second round of species to the NAPPRA list and to update the Q-37 regulations.

SOURCES

Jung, T. et al. 2015 “Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora disease” Forest Pathology. November 2015; available from Resource Gate

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L. Parke, and K.O. Britton. 2012. Live Plant Imports: the Major Pathway for Forest Insect and Pathogen Invasions of the US. www.frontiersinecology.org

Posted by Faith Campbell

![PHYTRA_06[1]](http://nivemnic.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PHYTRA_061.jpg)

PSHB damage to coast live oak;

PSHB damage to coast live oak;