I recently posted a blog based on a new report evaluating Canada’s invasive species efforts across all taxa (see Reid et al. reference at the end of this blog). That report focused on federal measures aimed at preventing introductions, including cross-border introductions from the U.S. After posting that blog I learned about a second report by Allison, Marcotte, Noseworthy and Ramsfield (2021) that focuses on non-native insects and diseases that threaten Canada’s trees and forests.

The first report’s authors lamented that invasive species responsibilities are divided among several agencies, depending on the associated commodity or resource. It noted claims by the Canadian government in its 2018 report to the Convention on Biological Diversity to have identified priority pathways. These included several relevant to forest pests: shipping, horticulture, transport containers, and recreation. The Government claimed that the wood packaging, forestry products, and plant products pathways were at least partially regulated and also that national plans had been developed for several priority species, including the Asian subspecies of Lymantria dispar and the emerald ash borer. Reid et al. (2021) included four case studies, two of which dealt with non-native forest pests: successful eradication (the second time around) of the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB); and the high threat to Canada posed by the spotted lanternfly (SLF).

I was pleased to learn of the second 2021 report (Allison, et al.) because of its focus on pests in trees and forests. This is important because U.S. and Canada share four types of forests; evergreen needle leaf forests, sparse trees/parkland, mixed broadleaf / needle leaf forests, and deciduous broadleaf forests (See Fading Forests III, Chap. 1, Fig. 1, Box 2 [link at end of this blog]). Together, North American forests are comprised of 1,165 different native tree species. They offer many potential hosts to any introduced insect or pathogen. Thus the two countries need to coordinate pest-prevention and responses when prevention fails.

It is more likely that a pest from overseas will be introduced first to the U.S. because the U.S. imports a much higher volume of goods and has greater variety of climates and forests. Data show this: as of 2010, more than 181 exotic insects that feed on woody plants were established in Canada (USDA 2009) compared to at least 475 in the U.S. (Aukema et al. 2010). However, sometimes a pest is first introduced in Canada, then spreads south. One examples is beech bark disease.

Forests occupy 40% of Canada’s land cover. Because the country is so large, there are a wide variety of ecozones and forest regions. Almost all (95%) regenerate naturally; 90% are publicly owned (federal and provincial). These forests, which equate to 9% of the Earth’s total forest area, are important not just to Canadians but also to the world for water regulation, carbon sequestration, habitat for biological diversity and the economy. (See Fig.1 in Allison et al.)

Both Canadian reports emphasize Canada’s international obligations, especially under the Convention on Conservation of Biodiversity (CBD). (This is far more than in similar U.S. reports; of course, the U.S. is not a party to this convention.) Allison et al. also mention the Montréal Process Working Group on Criteria and Indicators for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate and Boreal Forests; international carbon emission mandates and agreements; and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). Allison et al. also stress the importance of international collaborative research, mentioning the International Forestry Quarantine and Regulations Group (IFQRG), expert groups convened by the IPPC and North American Plant Protection Organization (NAPPO), Plant Health Quadrilateral Working Group and participation in the annual USDA interagency research forum on invasive species.

Both new Canadian reports focus on federal efforts, especially those of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), and Canadian Forest Service of Natural Resources Canada (CFS).

CFIA (Canada’s national plant protection organization, or NPPO in IPPC parlance) is responsible for analyzing risks, setting policy, and managing responses to forest biosecurity incursions. Its authority comes from Canada’s Plant Protection Act and Regulations (S.C. 1990, c. 22). The CBSA enforces regulations at most, but not all, international ports of entry. The CFS conducts research and analysis to support development and implementation of phytosanitary regulations. CFS is also charged with maintaining market competitiveness for forest products and meeting the country’s global commitments to sustainably develop its natural resources. The 10 provinces and three northern territories have jurisdiction over most of the country’s forests, including promoting forest health. Thus, protection and management of Canada’s forests is a shared responsibility among federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and indigenous governments and other stakeholders including the forest industry and non-governmental organizations.

Allison et al. (2021) discuss the effects of invasions on forest ecosystems, including altering forest ecology and the ability of forest ecosystems to provide services. For instance, invasions can change: competitive interactions among tree species; forest food webs; microenvironments; nutrient cycles; successional trajectories; understory plant communities; transpiration rates; water dynamics; and nitrogen and carbon flows, including carbon sequestration and storage. They cite the emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease as examples.

Much of these authors’ discussion of invasion processes, bioinvaders’ impacts and biosecurity procedures is familiar from a U.S. point of view. However, I appreciate that they explicitly concede knowledge gaps in three particular situations.

First, when discussing the absence of recognized ecological impacts associated with most introduced forest insects and pathogens, they state that this lack of known impacts is often likely due to an incomplete understanding of complex phenomena and delays in perception of effects. They cite — again — the case of the emerald ash borer, when impacts were reported only 10 years or more after its establishment.

Second is their discussion of the drivers of invasion. After saying that the interactions of species’ traits, introductory pathways, and receiving habitats are incompletely understood, they note that it is difficult to determine the relative contribution of reproductive traits and propagule pressure in explaining the invasion success of Hemiptera – which reproduce asexually but are also extremely common in invasion pathways. As I have said in a previous blog, the report due by Haack and colleagues later this year can help clarify the current contribution of the wood packaging pathway to propagule pressure.

Third, they note the limited predictive power of border interception records – and possibly other data resources such as risk assessments, surveillance programs – as a basis for understanding pathways. They note that Ips typographus has been intercepted hundreds of times by North American authorities but has never established.

There are some puzzling gaps in Allison, et al. For example, in discussing the costs associated with forest pest introductions, they do not mention the risk to “leaf-peeper” tourism – as U.S. evaluations of the Asian longhorned beetle do. In discussing the role of propagule pressure they mention pathway volume (i.e., the amount and frequency of trade) and the invasive species’ population levels in the point of origin, but not the invader’s ability to exploit the pathway. (Perhaps that is assumed within the pathway volume measurement?) The example cited is heightened arrivals of Lymantria dispar asiatica during periods of outbreak in its native Asian range.

The report provides helpful clarity on Canadian biosecurity practices. For example, wood packaging entering the country at thefour main Canadian commercial marine ports (Halifax, Montreal, Vancouver, and Prince Rupert) is inspected by CBSA. However, CFIA enforces compliance at the other marine ports and along the 8,891 km (5,500 mile) land-border with the U.S. Apparently CBSA joins in “border blitzes” at selected strategic land-border crossings.

In discussing the provinces’ efforts to slow the spread of established pests, the report mentions the western efforts to prevent introduction of Dutch elm disease. Also, it covers British Columbia’s attempt to prevent spread of balsam woolly adelgid (BWA) into its interior. (I mourn that this effort was not successful.)

The report cites the first record of the elm zigzag sawfly, Aproceros leucopoda in North America as an example of citizen detections.

I note that a periodic reassessment of the Canadian regulations governing emerald ash borer in 2014 resulted in a decision to expand the regulated area to reduce regulatory burden, increase awareness of the regulated areas, and maximize compliance. I regret that USDA APHIS decided to fully de-regulate the pest instead. Canada similarly expanded the regulatory zone for a second pest, the brown spruce longhorned beetle (in 2015).

Canada has deregulated pests judged to have spread to the limits of their potential invaded range, e.g., the Pine shoot beetle, Tomicus piniperda.

The report includes three case studies.

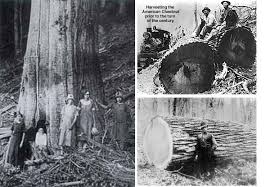

White Pine Blister Rust Case Study

This pathogen was introduced more than 100 years ago and has caused extensive damage to Canadian populations of the commercial species western white pine (Pinus monticola) and eastern white pine (P. strobus). It has also contributed to the decline of whitebark pine (P. albicaulis) and limber pine (P. flexilis). An early warning by Gussow (in 1916) about the pathogen’s probable impact apparently led Canada to prohibit further imports of five-needle pines.

Multiple consequences followed the pathogen’s spread. These included reduced volumes of eastern and western white pine due to the combined effects of disease-caused mortality and foresters shifting to alternative species to avoid future losses. Furthermore, both whitebark and limber pines have been ranked as “Endangered” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Whitebark pine is also listed on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act; limber pine is currently under consideration for such listing.

The report concludes by stating that resistance breeding is an important strategy and that extensive work has been carried out by both the U.S. and Canada.

Asian Longhorned Beetle Case Study

After noting that this pest of maples is of high concern in Canada, the report lays out the history of the first and second detections in Toronto. Because a risk assessment had been completed beforehand, actions could be taken rapidly. CFIA was encouraged to pursue eradication by the success of several previous eradication efforts, as well as the significant negative impact anticipated to the economy. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, NRCan-CFS, the cities of Toronto and Vaughan, and regional authorities and USDA – which shared information – all contributed. The program removed 5,000 trees in the first six months. In 2018, after five consecutive years of no detections, the ALB was declared eradicated. However, four months later, another ALB was reported – two km from the boundary of the first regulated area. The program was renewed, over a larger area. In total, considering both detections, more than 36,000 trees have been removed. Eradication of the pest following the second detection was declared in June 2020.

The report attributes success to 1) surveillance following IPPC guidelines; 2) reliance on science for evidence-based decision-making, including input on several issued by a science committee chaired by CFS; 3) Early engagement of partners and proactive communication that increased public awareness and reporting.

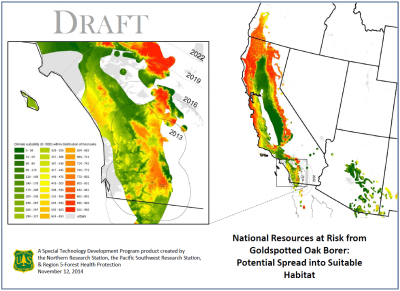

Oak Wilt Case Study

Oak wilt is established in U.S. states that border Ontario. Also, models suggest that the disease (Bretziella fagacearum) would not be limited by Canada’s climate and that it would cause serious economic harm. Therefore, Canada considers it to pose a high risk. Consequently, CFIA led development of a response framework to guide an incursion response. As usual, this was done in collaboration with representatives from federal, provincial and municipal governments, plus New York and Michigan.

Oak wilt is regulated under the federal Plant Protection Act. In addition to adopting various CFIA directives related to imports, the framework includes a communication strategy; provisions for detection and monitoring; and management activities aimed at its eradication if it is discovered in Canada. The framework also identified research needs and provided funding to address them. map from photos

In their conclusion, Allison, et al. (2021) state that the close relationship between CFIA and CFS is unusual but do not explain how or why.

They also suggest several ways Canada’s biosecurity efforts targetting non-native forest pests could be improved. The first is to increase information-sharing between agencies and with partners, plus better integration of information into policy development. Also, they suggest adoption of new post-border technologies (e.g., “smart” technologies; in-field chemical analyses, and optimization of surveillance programs) and additional research to build a stronger scientific understanding of pest biology, epidemiology, and trade economics. Generally, their recommendations do not overlap with those of Reid et al. (2021) – which was probably being written at the same time. They do both seem to suggest: 1) strengthening partnerships with the public and Indigenous communities and 2) to be prepared to adapt to future conditions.

SOURCES

Allison JD, Marcotte M, Noseworthy M and Ramsfield T (2021) Forest Biosecurity in Canada – An Integrated Multi-Agency Approach. Front. For. Glob. Change 4:700825. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2021.700825 Frontiers in Forests and Global Change July 2021 | Volume 4 | Article 700825

Aukema, J.E., D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle, A.M. Liebhold, . Britton, and S.J. Frankel. 2010. Historical Accumulation of Nonindigenous Forest Pests in the Continental United States. BioScience • December 2010 / Vol. 60 No. 11 www.biosciencemag.org

Reid CH, Hudgins EJ, Guay JD, Patterson S, Medd AM, Cooke SJ, and Bennett JR. 2021. The state of Canada’s biosecurity efforts to protect BD from species invasions. FACETS 6: 1922– 1954. doi:10.1139/facets-2021-0012 Published by: Canadian Science Publishing connorreid@cmail.carleton.ca

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2009. Risk analysis for the movement of solid wood packaging material (WPM) from Canada into the US.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm