Since Fiscal Year (FY)2009, APHIS has had access to a program that has permanent funding, not subject to the vagaries of annual budgeting and appropriations. The Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Prevention Program established by 7 U.S.C. Section 7721. The program was initially funded at $12 million for FY2009; $45 million in FY2010; $62.5 million in 2014-2017; and $75 million since FY2018.

Funds are provided under a competitive grants program to universities, states, Federal agencies, nongovernmental organizations, non-profits, and Tribal organizations “to conduct critical projects that keep U.S. crops, nurseries, and forests healthy, boost the marketability of agricultural products within the country and abroad, and help us do right and feed everyone.” [USDA press release “USDA Provides $66 Million in Fiscal Year 2019 to Protect Agriculture and Natural Resources from Plant Pests and Diseases” February 15, 2019]

By my calculation, total funding of tree pests projects during the period Fiscal Year (FY09) through FY20 was about $94 million. This represented 15.6% of nearly $600 million in total funding under the program during this period.

In the initial years, forest pest projects received about 10-12% of total funds. In later years, the proportion has been higher – e.g., 30% in FY19, 13.8% in FY20. The early years were dominated by management of the sudden oak death pathogen (SOD), Phytophthora ramorum. In FY09, SOD projects receive $7.5 million, or 8% of all tree pest funding. This funding helped set up the National Ornamental Nursery study center (NORS-DUC); later years paid for research projects on SOD management issues and nursery surveys.

In the most recent years, funding has been dominated by detection, management, and research on spotted lanternfly – which is not primarily a forest pest. Thus, in FY 19, 56.8% ($10,339,126) of $18,195,000 allocated to tree pests; in FY20, 30% ($2,606,094) of the $8,705,920 allocated to all tree pests.

The FY2019 program also provided $1,107,965 in 14 states and nationally for P. ramorum survey, diagnostics, mitigation, probability modeling, genetic analysis, and outreach (USDA press release 2019). This was appropriate considering the shipment of SOD-infected plants to nurseries in 18 states in spring 2019.

Current Year Funding

APHIS has released the list of projects funded under the Plant Protection Act Section 7721 in FY2021. Link to website APHIS funded 354 projects in 49 states, Guam, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, at a total cost of $63.225 million. APHIS is retaining ~ $14 million to allow responses to pest and plant health emergencies. Total funding for forest pests – by my calculation – was $8,715,046 (13.7% of the total).

My analysis finds that in FY21, 13 states had no funded projects that applied to tree pests: Arizona, Colorado, District of Columbia, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Utah.

Most commonly funded projects:

- Surveys and other efforts addressing wood borers: 37 projects, including

- Thousand cankers disease: 4 (all surveys)

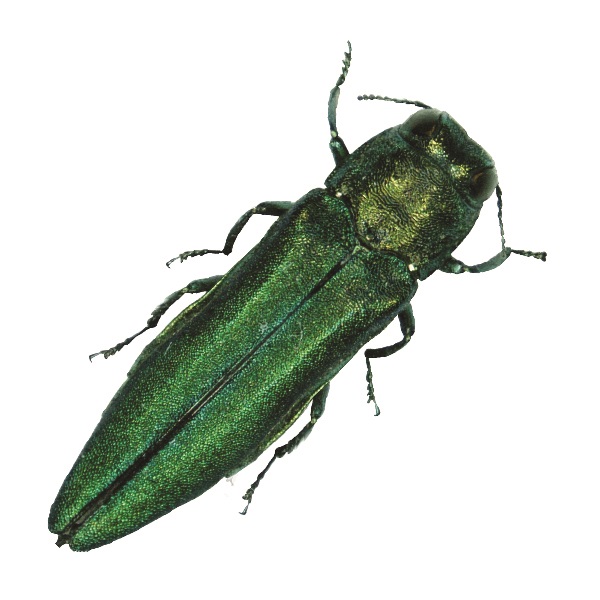

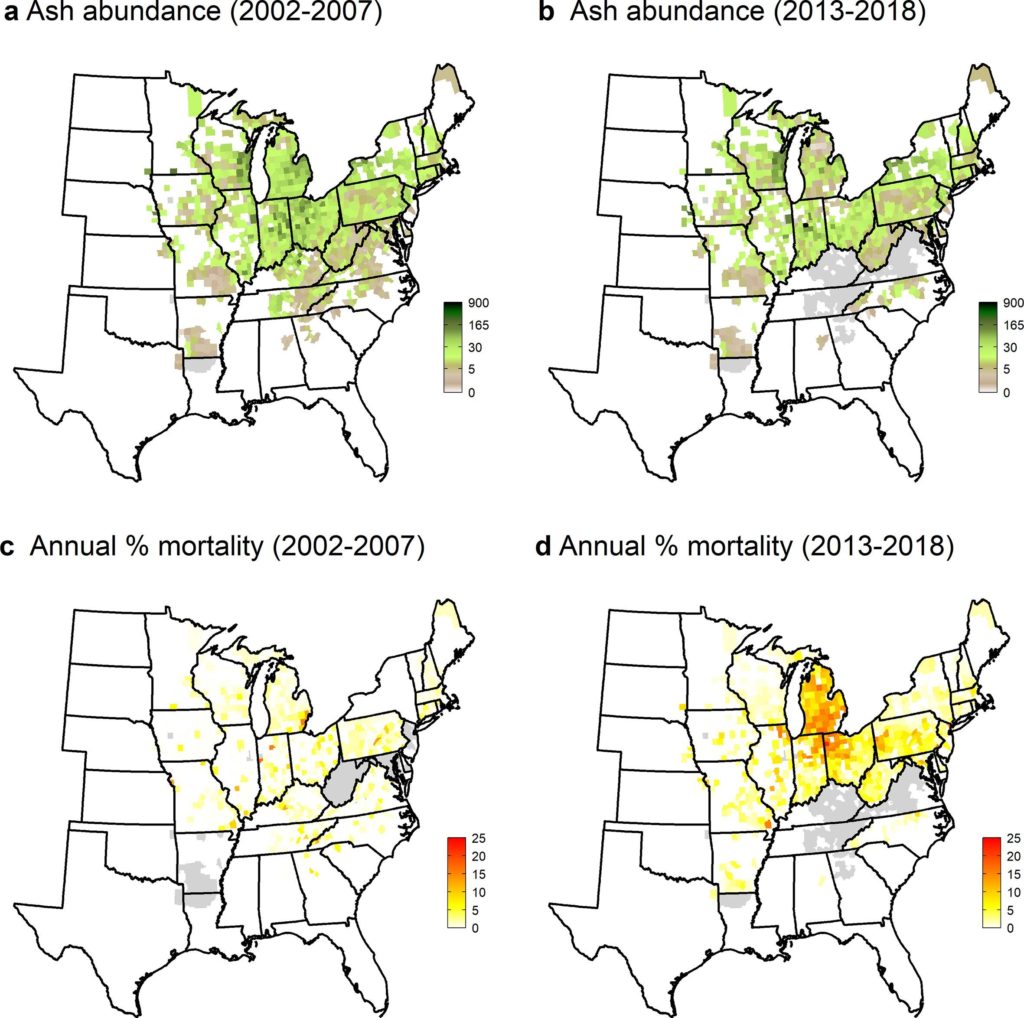

- Emerald ash borer: 6 projects (surveys and management, including biocontrol)

- Asian longhorned beetle: 3, of which 2 are outreach

- Laurel wilt disease: 1 project

- Detection tools for wood-borers, including citrus longhorned beetle, Sirex noctilio, Agrilus biguttatus, and Australian Cerambycids

- Phytophthora ramorum: 20 projects, primarily nursery surveys but including a few management projects. The projects were in 18 states.

- Surveys for Asian defoliating moths in the Lymantra genus: 15 projects

- Surveys and control efforts targetting spotted lanternfly: 13 projects in 6 states. These included research conducted by the APHIS Otis laboratory in Massachusetts. The grants totaled $2,788,010, or 32% of total forest pest funding.

APHIS funded 16 outreach projects (there is some overlap with above), including three specifically mentioning firewood. The latter included principal funding for the “Don’t Move firewood” national campaign.

Other projects that I find interesting:

- 2 projects targetting hemlock woolly adelgid

- 1 targetting red palm weevil

- 4 projects targetting Asian giant hornet in Washington and Oregon and the APHIS Otis laboratory. California has a project relating to a wider range of hornets that was also funded in FY20.

- Biocontrol of several invasive plant species in Florida – Australian pine/Casuarina, Brazilian pepper, and Ailanthus

As readers of this blog know, I also care deeply about threats to our native cacti – especially flat-padded Opuntia and tubular cacti endemic to Puerto Rico. Over the 13 years of program, funded following projects for cacti:

- FY11 $244,368 for efforts to develop sterile insect methodology to control cactus moth

- FY17 develop biocontrol for Harissia cactus mealybug $210,000

- FY19 Harissia cactus mealybug – $355,774; cactus moth $216,243

- FY20 Harrisia cactus mealybug $301,930

- FY 21 cactus moth biocontrol $175,659 and $352,236 for Harrisia cactus mealybug biocontrol

Clearly, having access to $75 million that is not subject to the limits imposed by Administration budget priorities or Congressional appropriations has allowed considerable freedom. The fund has allowed APHIS to support work on pests that have not been designated “quarantine pests,” e.g., walnut canker disease of walnut, the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers, hemlock woolly adelgid, and the cactus pests. The program also funded many projects targetting the spotted lanternfly (SLF) – both before and after the lanternfly became a formal APHIS program (which occurred after it was detected outside Pennsylvania). Now that SLF has been found in several states, funding has partially shifted to appropriated funds. The FY21 appropriation included an additional $4 million for management of SLF; this was incorporated in the “specialty crops” line item.

So far, there has been no funding for beech leaf disease through this program; I don’t know whether any of the people working on this disease had applied.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm