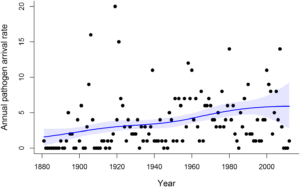

The number of new pathogens discovered each year on 131 focal host plant species in New Zealand (closed circles) and the mean annual rate of pathogen arrival estimated from the model (solid blue line), with shading showing the 95% credible interval.

Benjamin A. Sikes and several coauthors (article available here; open access!) find that targetted biosecurity programs can reduce the establishment of nonnative pathogens even while global trade and travel continue to increase.

The study relies on data from New Zealand because that country has more than 150 years of data on phytosanitary policies and pathogen introductions. Do other countries have data that would support a comparative study in order to test the authors’ conclusions more generally?

The study is unusual in analyzing introductions of a variety of forms of pathogens (fungi, oomycetes, and plasmodiophorids) rather than invertebrates. Pathogens pose significant plant health risks but are notoriously difficult to detect. The study used data on plant-pathogen associations recorded in New Zealand between 1847 and 2012. It focused on hosts in four primary production sectors: crops (46 species, including wheat, tomatoes, and onions); fruit trees (30 species, including grapes, apples, and kiwifruit); commercial forestry (42 species, including pines and eucalypts); and pastures (13 species of forage grasses and legumes). In total, 466 pathogen species for which the first New Zealand record was on one of these 131 host plants were included in the study. The pathogens were assumed to have arrived on imports seeds or fresh fruits of plants in the same family as the 131 hosts in the various production sectors.

After calculating each pathogen’s probable date of introduction, the authors compared those dates to contemporaneous levels of imports and incoming international travellers. Sikes et al. applied statistical techniques to adjust their data to the fact that detection of pathogens is particularly sensitive to variation in survey effort.

Findings:

- The annual arrival rate of new fungal pathogens increased exponentially from 1880 to ~1980 in parallel with increasing import trade volumes. Subsequently rates stabilized despite continued rapid growth in not only imports but also in arrivals of international passengers.

- However, there were significant differences among the four primary production sectors.

- Arrival rates for pathogens associated with crops declined beginning in the 1970s but slightly earlier for those associated with pasture species. These declines occurred despite increasing import volumes.

- Arrival rates of pathogens that attack forestry tree species continued to increase after 1960.

- Arrival rates for pathogens that attack fruit tree species remained steady while import volumes rose steadily

Sikes et al. attribute these contrasting trends between production sectors to differences in New Zealand’s biosecurity efforts. They record when phytosanitary restrictions targetting the four sectors were adopted and link those changes to reductions in numbers of pathogens detected a decade or so later. They conclude that targetted biosecurity can slow pathogen arrival and establishment despite increasing trade and international movement of people.

Regarding the contrasting situation of the forestry and fruit tree sectors, Sikes et al. note that while phytosanitary inspections of timber imports was initiated in 1949, it focussed primarily on invertebrate pests. In addition, surveys for pathogens on fruit tree and forestry species were less robust than in the cases of crop and pasture species, and the peak survey effort occurred several decades later – in 1980 for fruit trees, 2000 for forestry species.

Furthermore, pathogens of forestry and fruit tree species can be introduced on types of imports other than seeds and fresh fruits, including soil and live plant material (e.g., rootstock) and untreated wood products.

Sikes et al. say there is no evidence of slowed pathogen arrival rates resulting from imposition of post-entry quarantine to live plant material beginning in the 1990s. I find this very troubling. Post-entry quarantine is a high-cost strategy. Still, several plant pathologists have advocated adoption of this strategy because they believed it would be sufficiently more effective in preventing introductions of – especially! – pathogens as to be worthwhile. Do others have data with which to add to our understanding of this disturbing phenomenon?

The authors suggest that introductions of tree-attacking pathogens on rising imports of wood packaging might have swamped decreases in introductions via other vectors. They consider that implementation of International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) No. 15 in 2002 means it is too early to see its impact in detection data. As I have blogged several times, implementation of ISPM#15 by the United States, at least, has reduced presence of detected pests – primarily insects – by 52%. Little is known about the presence of pathogens on wood packaging – according to some experts, inspectors rarely even look for pathogens. So I think the authors’ suggestion might not fully explain the continuing introduction of pathogens that attack tree species used in plantation forestry in New Zealand.

Prof. Michael Wingfield of South Africa has written numerous articles on the spread of pathogens that attack Eucalyptus on seeds imported to establish plantations in various countries; one such article is available here. This seems a more likely explanation to me.

The study’s analysis demonstrated that the overall rate of non-native fungal pathogen establishment in New Zealand was more strongly linked to changes in import trade volume than to changes in numbers of international passengers arriving on the islands. Although Sikes et al. don’t explicitly raise the question, they note that New Zealand has put considerable effort into screening incoming people – which appears from these data to have a smaller payoff than imposing phytosanitary controls on imports.

Recent declines in surveys mean the authors must estimate current pathogen arrival rates. The data gaps exacerbate the inevitable uncertainty associated with the time lag between when an introduction occurs and when it is detected. They estimate that an average of 5.9 new species of fungal pathogens per year have established on the focal host plant species since 2000. They estimate further that 55 species of pathogens are present in New Zealand but have not yet been detected there.

I am quite troubled by the reported decline in New Zealand’s postborder pathogen survey efforts since about 2000. This appears very unwise given that the risk of new introductions of pathogens that attack fruit and forestry trees continues – or even rises! Indeed, scientists associated with the forestry industry note the risk to Douglas-fir and Monterrey (Radiata) pine plantations from the pitch canker fungus Fusarium circinatum – which could be introduced on imported seeds, nursery stock, and even wood chips. Radiata pine makes up 92% of softwoods planted – and exotic softwoods constitute 97% of the plantation forestry industry.

Furthermore, non-native pathogens threaten New Zealand’s unique forest ecosystems. Since this study focused on non-native plant hosts, it does not address the risk to native forest species. However, the threat is real: Kauri trees – the dominant canopy species in some native forest types – is suffering from a dieback caused by an introduced Phythopthora. Also, two other pathogens threaten the many trees and shrubs in the Myrtaceae family found in New Zealand – Puccinia rust (which is established in Australia but not New Zealand) or the Ceratocystis fungi causing rapid ohia death – both threaten native forests in Hawai`i, as discussed in a recent blog.

Furthermore, non-native pathogens threaten New Zealand’s unique forest ecosystems. Since this study focused on non-native plant hosts, it does not address the risk to native forest species. However, the threat is real: Kauri trees – the dominant canopy species in some native forest types – is suffering from a dieback caused by an introduced Phythopthora. Also, two other pathogens threaten the many trees and shrubs in the Myrtaceae family found in New Zealand – Puccinia rust (which is established in Australia but not New Zealand) or the Ceratocystis fungi causing rapid ohia death – both threaten native forests in Hawai`i, as discussed in a recent blog.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

laurel-wilt killed swamp bay in the Everglades

laurel-wilt killed swamp bay in the Everglades

dogwood anthracnose

dogwood anthracnose