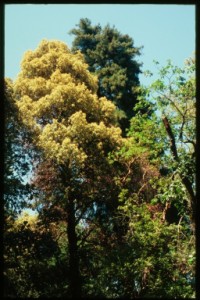

Phytopthora ramorum on tanoak in California; F.T. Campbell

Nine eastern states are participating in the 2016 USDA National Phytophthora ramorum Early Detection Survey of Forests. Those states are AL, FL, GA, MS, NC, PA, SC, TN, and TX. As of late August, streams in four locations were P. ramorum-positive. Three are in AL, one in MS. All had tested positive in previous years. Also, all have been associated with previously positive nurseries. (Reported in the California Oak Mortality Task Force newsletter for September.) It is reassuring that no new positive locations have been detected. However, on what substrate is the pathogen persisting? Scientists agree that the pathogen does not survive in water (although it is reliably detected by testing in water) but must survive on some plant material – perhaps roots.

P. ramorum also persists in nurseries. Seven California nurseries are participating in the APHIS federal P. ramorum program under which they are allowed to ship host plants interstate. Positive plants have been detected in two of them. One of these nurseries is undergoing the Confirmed Nursery Protocol clean-up. The other has completed the cleanup and has been allowed to resume shipping plants interstate. In both cases, the infected plants were not from the five “high-risk” genera which are the focus of monitoring for the regulatory system — Camellia, Kalmia, Pieris, Rhododendron, and Viburnum. (Reported in the California Oak Mortality Task Force newsletter for September.) I expressed concern about this too-narrow focus in a blog posted in July 2015 – http://nivemnic.us/2015/07/.

I have written about the widespread presence of various Phytophthoras in nurseries in blogs in April (for Europe http://nivemnic.us/2016/04/ ) and July (for California http://nivemnic.us/2016/07/ ). New publications add to this picture.

Junker and colleagues (see references below) report the detection of 15 Phytophthora species in two commercial woody ornamental nurseries (presumably in Europe, since the authors are Europeans). Twelve of the species are previously described but the DNA of three isolates did not match any of the known species. Detections were highest in puddles on nursery pathways; followed by plant residues;, wind-carried leaves; and water and sediment from runoff. The plant samples showed very low infection rates – a disturbing finding given the reliance until recently on inspection of plants to detect the pathogen. (Reported in the California Oak Mortality Task Force newsletter for September.)

New Phytophthora confirmed in U.S.

The United States has the first official confirmed detection of the pathogen Phytophthora quercina. It was found associated with oak trees planted on restoration sites in central coastal California. Although the California detection is the first officially confirmed detection of the pathogen in the U.S., a P. quercina ‘like’ organism has been reported to be associated with oak decline in forests in the Midwest. P. quercina is a pathogen associated with oak decline across Europe. It was rated as the species of highest concern in a USDA Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory (PERAL) report. Another pathogen, P. tentaculata, was rated fifth on the same list. It was recently found in association with multiple native plant species in California’s native plant nurseries (see my July blog, linked above). See also California Oak Mortality Task Force newsletter at http://www.suddenoakdeath.org/news-and-events/current-newsletter/

Rapid Response Might Have Contained SOD – When will authorities learn this lesson?

Earlier this year, experts on modeling the epidemiology of plant disease concluded that the sudden oak death epidemic in California could have been slowed considerably if aggressive management actions – backed by “a very high level of investment” – had started in 2002. By then, there was sufficient knowledge about the disease to guide actions. Management actions should have focused on the leading edge of the epidemic (admittedly, that edge has proven difficult to detect). The study is by American and British scientists (Cunniffe, Cobb, Meentemeyer, Rizzo, and Gilligan). See reference and news report below.

The authors’ estimate documents the high costs of inaction. This is an important lesson – which has been repeated many times. If only officials from California and APHIS would take this to heart regarding several other forest pests. These include the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers and even the goldspotted oak borer (all described here).

References

Cunniffe, N.J., R.C. Cobb, R.K. Meentemeyer, D.M. Rizzo, and C.A. Gilligan. Modeling when, where, and how to manage a forest epidemic, motivated by SOD in Calif. PNAS, May 2016 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1602153113

Junker, C., Goff, P., Wagner, S., and Werres, S. 2016. Occurrence of Phytophthora in commercial nursery production. Plant Health Progress. 17:64-75.

Posted by Faith Campbell

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

F.T. Campbell dead sweetbay, Florida Everglades

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission

willow tree in Tijuana River riparian area felled by KSHB. Photo by John Boland; used by permission