The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has taken new action to protect North America’s salamanders from the pathogenic Salamander Chytrid Fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans; Bsal). The Center for Invasive Species Prevention (CISP) welcomes this action and urges you to help the Service to finalize it.

To read and comment on the interim rule, go here. The comment period closes on March 11.

USFWS acted under its authority to contained in the “injurious wildlife” provisions of the Lacey Act [18 U.S.C. 42(a)]. This statute, first adopted in 1900, empowers the Secretary of Interior to regulate human-mediated transport of any species of wild mammal, wild bird, fish, mollusk, crustacean, amphibian, or reptile found to be injurious to human beings; to the interests of agriculture, horticulture, or forestry; or to America’s wildlife or wildlife resources. Regulated articles include offspring or eggs of the listed species, dead specimens, and animal parts.

Any importation of a listed taxon into the U.S. is regulated. However, regulation of transport within the United States is complicated because of clumsy wording of the statute. In 2017, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals [U.S. Association of Reptile Keepers, Inc. v. Zinke [852 F.3d 1131 (D.C. Cir. 2017)] ruled that the law regulates transport of listed species (and their progeny, parts, etc.) between the contiguous 48 States and several other jurisdictions: Hawai`i, Puerto Rico, other U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia. However, transport among the “lower 48” states (e.g., from Virginia to Kentucky) or from the “lower 48” states to Alaska, is not regulated (unless the route to or from Alaska passes through Canada). In past years conservationists asked Congress to amend the law to close this obvious gap in protection, but without success.

It is still illegal to transport listed species across any state borders if the wildlife specimen was either imported to the U.S. or transported between the above-enumerated jurisdictions in violation of any U.S. law. [Lacey Act Amendments of 1981, 16 U.S.C. 3372(a)(1)]

Those wishing to transport a listed species for zoological, educational, medical, or scientific purposes may apply for a permit from USFWS to do so.

The threat to salamanders

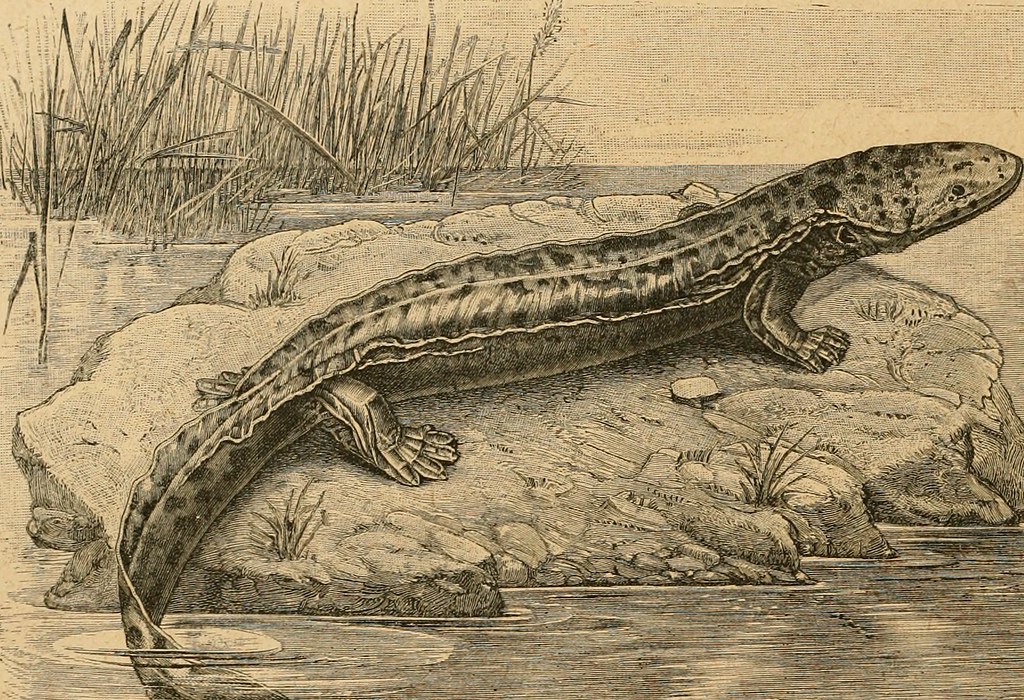

The United States is a center of diversity for salamanders. Our nation is home to 221 species of salamanders, more than any other country. These species are in 23 genera in nine families. In fact, nine of the 10 families of salamanders worldwide are found in the U.S. Highest diversity is found along the Pacific Coast and in the southern Appalachian Mountains. As the most abundant vertebrates in their forest habitats, salamanders make significant contributions to nutrient cycling and even carbon sequestration.

Because they depend on both aquatic and terrestrial habitats, salamanders face many threats to their existence. Twenty species of American salamanders from 6 genera (Ambystoma, Batrachoseps, Eurycea, Necturus, Phaeognathus, Plethodon) are listed under the Endangered Species Act link as endangered or threatened. A subspecies of hellbender salamander (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleghaniensis) has been proposed for listing.

Over the last 12 years, they have faced an alarming new threat.

In 2013, European scientists detected rapid, widespread death of salamander populations in the Netherlands. They determined that the cause was a fungal disease caused by Batrachochytrium salamandrivoran (Bsal). Their alarm was heightened because this fungus is closely related to another, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which had recently caused serious decline of more than 100 frog and toad species, including driving several to extinction, and had been transported to all continents except Antartica.

Responding to this new threat, amphibian conservation specialists and wildlife groups generally banded together to put pressure on the USFWS to take regulatory action. In response, in 2016, the USFWS adopted an interim rule link prohibiting importation of 20 genera of salamanders. These genera had been shown by scientists to contain at least one species which either suffered mortality when it was exposed to Bsal or could transmit the disease to other salamanders. At the time, Bsal had been shown by scientific studies to be lethal to two American species; USFWS had evidence that U.S. species in other genera could “carry” the pathogen and infect other animals. Three of the species included in the 2016 action had already been listed as endangered or threatened. USFWS’ action cut down the number of salamanders being imported annually by ~95% (based on official import data compiled by the USFWS’ Office of Law Enforcement).

The prohibitions do not apply to articles that cannot transmit the fungus. These include eggs or gametes; parts or tissues that have been chemically preserved, chemically treated, or heat treated so that the pathogen, if present, is rendered non-viable; and molecular specimens consisting of only the nucleic acids from organisms.

Now, 8 years later, the USFWS is acting to finalize the 2016 “interim” rule and to regulate importation and transportation of an additional 16 genera of salamanders. This step had been urged by the National Environmental Coalition on Invasive Species (NECIS), and many others, in their public comments on that Interim Rule. Extending protection to these 16 genera is based on research conducted since the 2016 Rule. Species in 13 of the newly protected genera are considered likely carriers of the disease. Nine species have been demonstrated to be killed by Bsal. No studies have yet determined the vulnerability of more than 50 species in 10 genera of North American salamanders, including four species listed under the Endangered Species Act.

The 36 genera covered by the combined actions of 2016 and 2025 actions are currently considered to comprise ~ 426 species. However, changes in taxonomy are frequent. So USFWS is no longer enumerating the species protected, but is instead relying on listing genera. The regulations apply to all species in a listed genus (whether so classified now or in the future) as well as hybrids of species in any listed genus, including offspring from a pair in which only one of the parents is in a genus listed as injurious.

USFWS chose to issue “interim” rules in both 2016 and 2025 because that action takes effect almost immediately. (The 2025 interim rule take effect on January 25th.) The usual rulemaking process governed by the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. 551 et seq.) often takes years to complete. During that time, the species proposed for listing may still be imported and transported – that is, they could place additional salamander populations at risk of infection by Bsal. The USFWS states that it is unlikely to be able to protect or restore species and ecosystems if the pathogen does become established in the U.S.

In the interval between 2016 and now, Canada banned importation of all living or dead salamanders, eggs, sperm, tissue cultures, and embryos in response to the Bsal threat.

During these years scientists also completed several studies aimed at clarifying which salamander species are either at risk of infection by Bsal or are able to harbor and transmit the pathogen to other salamanders. The USFWS cites studies by, inter alia, Yuan et al. 2018, Carter et al. 2020, Barnhart et al. 2020, Grear et al. 2021, and Gray et al. 2023. USFWS says it cannot act in the absence of such studies, since it must justify its protective actions on scientifically defensible information.

Another relevant question is whether Bsal is already established in North America? Waddle et al. 2020 carried out an intensive search in 35 states that found no evidence that it is. The USFWS concludes that prohibiting importation of additional salamander taxa is still an effective measure to protect North American biodiversity. This is because the international commercial trade in salamanders is the most likely pathway by which Bsal would be introduced to the United States. We note in support of this assertion that former USFWS employee Su Jewell found years ago that none of the 288 non-indigenous species listed as injurious while they are not established in the U.S. has become established since the listing.

The Federal Register document includes a lengthy discussions of why the USFWS has chosen to act under the Lacey Act rather than try some other approach, e.g., setting up quarantine areas or a disease-free certification program for traded salamanders. Among the factors they considered were the current absence of certainty in testing procedures and the possibility of falsified documentation.

WEAKNESSES THE LACEY ACT

The Lacey Act is the principal statute under which the U.S. Government tries to manage invasive species of wildlife – at least those that are not considered “plant pests”. It is not surprising that a law written 125 years ago is no longer the best fit for current conservation needs. See our earlier blog and discussions by, inter alia, Fowler, Lodge, and Hsia and Anderson.

Here, the USFWS lacks authority to regulate pathogens [viruses, bacteria, and fungi that cause disease] or fomites (materials, such as water, that can act as passive carriers and transfer pathogens). Instead, USFWS regulates the hosts. The USFWS previously listed dead salmonids as “injurious” because their carcasses can transmit several viruses.

Another issue is that USFWS cannot designate a taxon “injurious” and regulate trade in it until the Service has conclusive scientific evidence that the species or genus meets the definition. The USFWS has chosen to rely on genus-level data rather than require that each species be tested. Still, as we noted above, American salamanders in 10 genera remain outside the Lacey Act’s protections because studies have not yet been conducted. The USFWS concedes that many of these genera might contain species that are vulnerable to this potentially deadly fungus.

As to relying on laboratory tests of a taxon’s response to the pathogen, the USFWS believes that environmental stresses inherent living in the wild might exacerbate a salamander species’ vulnerability to the disease.

The USFWS is requesting public comment specifically on:

(1) the extent to which species in the 16 genera listed by this interim rule are currently in domestic production for sale – and in which States this occurs? How many businesses sell salamanders from the listed genera between enumerated jurisdictions (e.g., between “lower 48” states and Hawai`i or the District of Columbia)?

(2) What state-listed endangered or threatened species would be affected by introduction of Bsal?

(3) How could this interim rule be modified to reduce costs or burdens for some or all entities, including small entities, while still meeting USFWS’s goals? What are the costs and benefits of the modifications?

(4) Is there any evidence suggesting that Bsal has been established in the U.S.? Or that any of these genera are not carriers of Bsal? Or that additional genera are carriers of Bsal? Is there evidence that eggs or other reproductive material pose a greater risk than USFWS determined, so should be regulated?

(5) Could a reliable health certificate system be developed that would allow imports of Bsal-free salamanders? Are there treatments that would ensure imported salamanders are reliably free of Bsal? How could compliance be monitored? As to salamander specimens, parts, or products, are there other treatments proven adequate to render Bsal non-viable?

(6) Do any Federal, State, or local rules duplicate, overlap, or conflict w/ this interim rule?

CISP encourages those with knowledge of amphibian conservation and disease to comment. Slow progress has been made toward blocking Bsal from the U.S., but the story is not yet closed.

See also the articles by Su Jewell,

Jewell, S.D. 2020 A century of injurious wildlife listing under the Lacey Act: a history. Management of Biological Invasions 11(3): 356–371, https://doi.org/10. 3391/mbi.2020.11.3.01

Jewell, S.D. and P.L. Fuller 2021 The unsung success of injurious wildlife listing under the Lacey Act. Management of Biological Invasions 2021 Volume 12 Issue 3

Posted by Faith Campbell and Peter Jenkins (former member of CISP’s board and consultant to NECIS and other groups on amphibian disease regulation)

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.