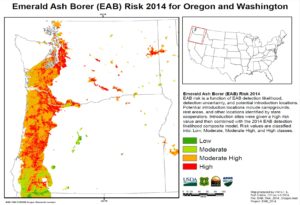

EAB risk to Oregon & Washington

EAB risk to Oregon & Washington

USDA APHIS has formally proposed to end its regulatory program aimed at slowing the spread of the emerald ash borer (EAB) within the United States. APHIS proposes to rely on biological control to reduce impacts and – possibly – slow EAB’s spread. The proposal and accompanying “regulatory flexibility analysis” are posted here.

Public comments on this proposed change are due 19 November, 2018.

I will blog more fully about this issue in coming weeks. At present, I am on the fence regarding this change.

On the one hand, I recognize that APHIS has spent considerable effort and resources over 16 years trying to prevent spread of EAB – with less success than most would consider satisfactory. (EAB is known to be in 31 states and the District of Columbia now). While APHIS received tens of millions of dollars in emergency funding in the beginning, in recent years funding has shrunk. Over the past couple of years, APHIS has spent $6 – $7 million on EAB out of a total of about $54 million for addressing “tree and wood pests.” (See my blogs on appropriations by visiting www.cisp.us, scrolling down to “topics,” then scrolling down to “funding”). Funding has not risen to reflect the rising number of introduced pests. Presumably partly in response, APHIS has avoided initiating programs targetting additional tree-killing pests. For example, see my blogs on the shot hole borers in southern California and the velvet longhorned beetle by visiting www.cisp.us, scrolling down to “categories,” then scrolling down to “forest pest insects”. I see a strong need for new programs on new pests and money now allocated to EAB might help fund such programs.

On the other hand, APHIS says EAB currently occupies a quarter of the range of ash trees in the U.S. Abandoning slow-the-spread efforts put at risk trees occupying three quarters of the range of the genus in the country. (See APHIS’ map of infested areas here.) Additional ashes in Canada and Mexico are also at risk. Mexico is home to 13 species of ash – and the most likely pathway by which they will be put at risk to EAB is by spread from the U.S. However, APHIS makes no mention of these species’ presence nor USDA’s role in determining their fate.

I am concerned by the absence of information on several key aspects of the proposal.

- APHIS makes no attempt to analyze the costs to states, municipalities, homeowners, etc. if EAB spreads to parts of the country where it is not yet established – primarily the West coast. As a result, the “economic analysis” covers only the reduced costs to entities within the quarantined areas which would be freed from requirements of compliance agreements to which they are subject under the current regulations. APHIS estimates that the more than 800 sawmills, logging/lumber producers, firewood producers, and pallet manufacturers now operating under compliance agreements would save between $9.8 M and $27.8 million annually. This appears to be a significant benefit – but it loses any meaning absent any estimate of the costs that will be absorbed by governments and private entities now outside the EAB-infested area.

- APHIS does not discuss how it would reallocate the $6 – 7 million it spends on EAB. Would it all go to EAB biocontrol? Would some be allocated to other tree-killing pests that APHIS currently ignores?

- APHIS provides no analysis of the efficacy of biocontrol in controlling EAB. It does not even summarize studies that have addressed past and current releases of EAB-specific biocontrol agents. (I will report on my reading of biocontrol studies in a future blog.)

- APHIS says efforts are under way to develop programs to reduce the risk of pest spread via firewood movement. APHIS does not explain what those efforts are or why they are likely to be more effective than efforts undertaken in response to recommendations from the Firewood Task Force issued in 2010.

- APHIS makes no attempt to analyze environmental impacts.

champion green ash in Michigan killed by EAB

- APHIS says nothing about possibly supporting efforts to breed ash trees resistant to EAB.

I welcome your input on these issues.

I will inform you of my evolving thinking, information obtained in efforts to fill in these gaps, etc. in future blogs.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

P. ramorum-infected seedlings in a nursery; photo by USDA APHIS

P. ramorum-infected seedlings in a nursery; photo by USDA APHIS