A year ago, I alerted you to a new threat to American beech (Fagus grandifolia). In that blog I reported that conservation and park managers in northeastern Ohio had begun noticing troubling decline and mortality of beech saplings beginning in 2012. The problem was spreading: we now know that over the four years between 2012 and 2016, the apparent disease spread from an estimated 84 ha to 2,525 ha within Lake County, Ohio (Ewing et al. 2018; full citation provided at end of the blog).

By 2018, trees with symptoms had been detected in 24 counties across three states and one province: 10 counties in Ohio, 8 counties in Pennsylvania, 1 county in New York, and 5 counties in Ontario). A map is provided in Ewing et al.

The rate of decline within beech stands varies, suggesting that trees differ in susceptibility. This is a promising for breeding resistance (Ewing et al.).

Symptoms

A number of organizations have produced fact sheets and related material. I recommend the fact sheet available here.

Disease Progression

In Northeast Ohio, Cleveland Metroparks’ intensive monitoring program revealed a 4% mortality rate from 2015 to 2017. More than half of the plots now have dead trees that had previously been only symptomatic. Most of the dead trees are small – less than 4.9 cm dbh. However, some larger trees have died and others bore only a few leaves this past summer. Leaves with light, medium, or heavy symptoms of infection – as well as asymptomatic leaves – can occur on the same branch of an individual tree.

The disease seems to spread faster between the stems of trees growing in beech clone clusters by spreading along the interlocking roots.

Serious science effort finally initiated – and funded!

The cause of beech dieback and mortality has still not been definitively determined. Most scientists agree that the cause is some kind of disease agent, not abiotic factors. A growing number of scientists from USDA’s Agriculture Research Service and Forest Service; Ohio’s Division of Forestry and Department of Agriculture; the Holden Arboretum; Ohio State University; and groups in Canada are researching possibilities.

The most promising candidate is a previously undescribed nematode detected by David McCann of the Ohio Department of Agriculture. That nematode has since been described by Japanese researchers on Japanese beech F. crenata (Kanzaki et al.) and given the name Litylenchus crenatae. Thousands of live Litylenchus nematodes (at least 10,000) can swim out from a single leaf. Scientists at the USDA Agriculture Research Service and Holden Arboretum are waiting for bud break this spring to see whether plant material inoculated with the nematode develops disease symptoms.

Still, other possible disease agents could also play a role.

An international working group has been formed to continue studies of both disease agents and disease progression in seedlings, saplings, and mature trees.

Still, no regulation to counter long-range spread via nurseries!

Long range spread of the disease is probably assisted by anthropogenic transport, especially of nursery stock. As I reported in May, an Ontario retailer received – and rejected – a shipment of diseased beech from an Ohio nursery.

Despite the evident risk, no official agency has adopted regulations to prevent spread on nursery stock. None of the states or provinces in which the disease is present has adopted regulations. None of the neighboring states or provinces has acted to protect its nursery industry or forests. Neither USDA APHIS nor the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has adopted regulations. The disease was not mentioned during the annual meeting of the National Plant Board – which took place in Cleveland in August! Connie Hausman of Cleveland MetroParks did include the issue during her presentation on the extensive park complex to the group during the group’s field trip.

The absence of regulation is a puzzling omission because Lake County, Ohio, has many nurseries that grow and ship European beech — which can also be infected by beech leaf disease.

The Importance of American Beech – and Protecting

Our American beech is not a major timber species – in fact, the species is actively disliked by managers focused on timber production because beech bark disease kills trees before they reach commercial size. Beech trees also often have cavities which reduce their timber value – but which are valuable to wildlife.

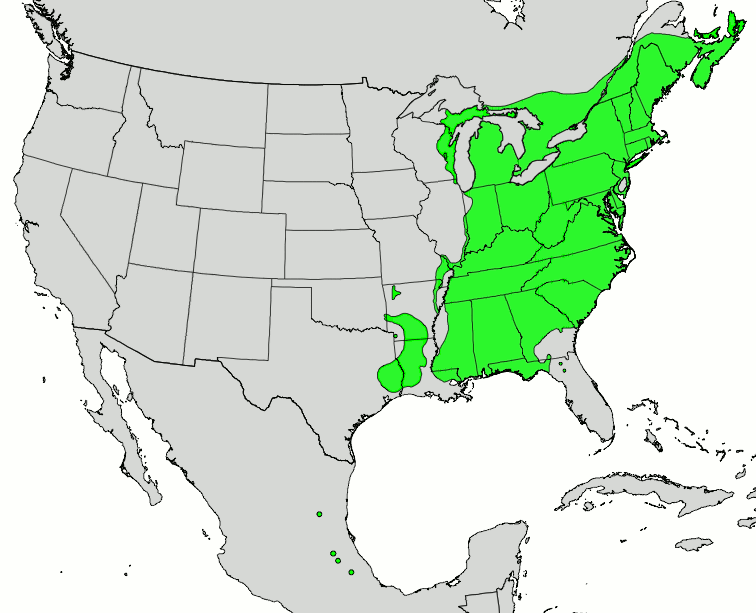

However, American beech is extremely important ecologically in northern parts of the United States and in Canada east of the Great Plains. Beech is co-dominant (with sugar maple) in the Northern Hardwood Forest. A summary of the species’ ecological importance can be found in Lovett et al. 2006. Beech nuts are a primary source of food for many woodland birds and mammals. In the central part of the northern hardwood forest – including in southern Canada – beech trees are the only source of hard mast. Furthermore, beech trees create a dense canopy; drastic defoliation modifies light levels at ground level, thereby affecting understory competition and other forest ecosystem services. Beech leaf litter decays more slowly than maple’s, which affects nutrient cycling. While beech leaf disease is unlikely to eradicate American beech, it could cause functional eradication of the species. Ohio alone has more than 17 million American beech trees, according to Tom Macy of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (Ewing et al. 2018).

The threat appears to be widespread because both European (F. sylvatica) and Asian (F. orientalis) beech have shown symptoms. Ewing et al. 2018 call for detection efforts across Northern Hemisphere.

Of course, the species is already under threat from beech bark disease. Promising efforts to breed beech trees resistant to BBD now face the complication of having to incorporate resistance to this new disease (Ewing et al. 2018).

European Beech Weevil

I will remind you that last year I noted a third threat to beech trees – the European leaf weevil. Originally detected in Nova Scotia, it continues to spread. About 95% of beech trees in forest plots near Halifax are dead. In the city, half the beech trees have died and the rest are in severe decline. While neither the province nor CFIA has imposed a quarantine or other regulations to govern the movement of beech material, Canadian officials are exploring possible chemical treatments. They are working with European colleagues to explore biocontrol agents (Jon Sweeney, Natural Resources Canada, pers. comm.).

Conclusion

These new threats are getting far too little attention! Some can be blamed on the difficulty of regulating an unknown disease agent (e.g., beech leaf disease). Attempting this would stretch traditional policy practice and, possibly, legal authorities. And it has not yet been demonstrated that this disease can kill mature beech. However, neither of these caveats applies to the weevil, which is an identified species, documented to kill mature trees, and a problem still not addressed.

Sources

Ewing, C.J., C.E. Hausman, J. Pogacnik, J. Slot, P. Bonello. 2018. Beech leaf disease: An emerging forest epidemic. Short Communication. Forest Pathology 2018;e12488

Kanzaki, N., Y. Ichihara, T. Aikawa, T. Ekino, and H. Masuya. 2019. Litylenchus crenatae n. sp. (Tylenchomorpha: Anguinidae), a leaf gall nematode parasitising Fagus crenata Blume. Nematology. Volume 21: Issue 1

Lovett et al. 2006. Forest Ecosystem Responses to Exotic Pests and Pathogens in Eastern North America. BioScience Vol. 56 No. 5.

Sharon Reed’s presentation on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tDBbik7cUrI

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.