We have long known that significant damage to our forests have been caused by non-native insects and diseases. Now USFS scientists have found that exacerbated mortality caused by these pests is showing up in official monitoring data – the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data. In a presentation at the 81st Northeastern Forest Pest Council, Randall Morin described the results of applying FIA data to determine mortality levels caused by several of the most damaging invaders. He found an approximately 5% increase in total mortality volume nation-wide.

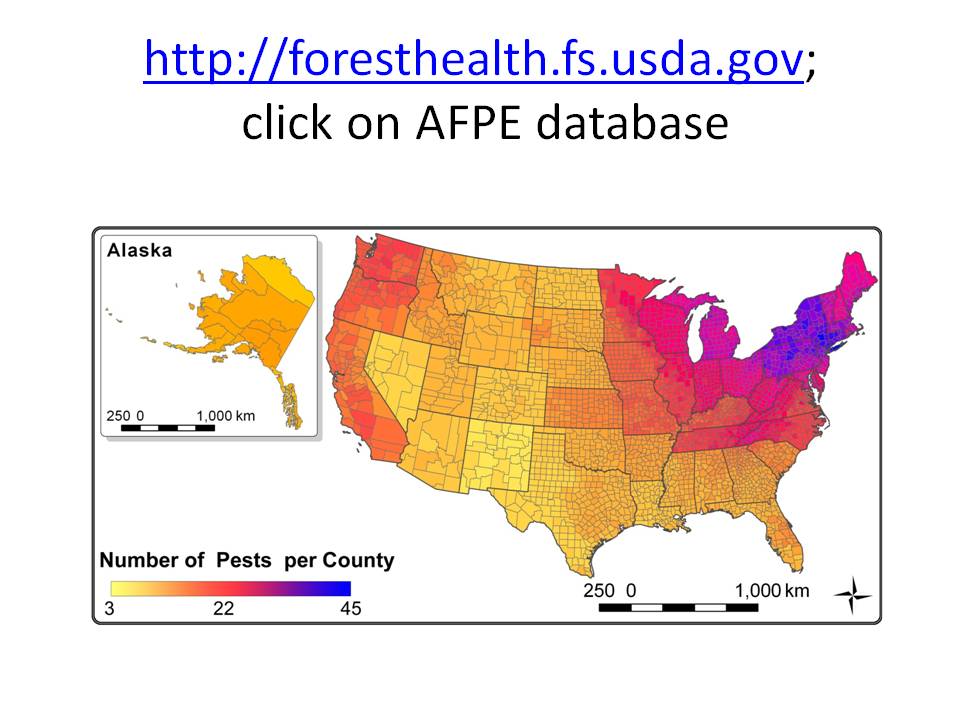

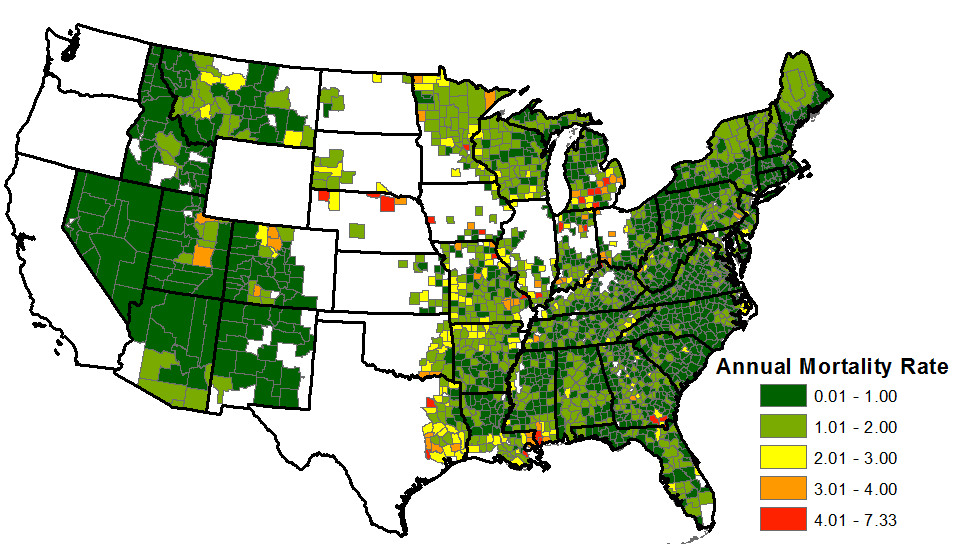

Morin also compared a map prepared by Andrew Liebhold showing the number of non-native tree-killing pests established in each county of the continent to the mortality rates for those counties based on the FIA data. (See two maps below.)

Counties showing the highest mortality rates in FIA data do not align with counties with highest numbers of invasive species. Morin thinks the discrepancy is explained by such human factors as invasion pressure and the ease of pest movement through the good transportation network in the Northeast. He assigns less importance to habitat invasibility.

The increase in mortality above the background rate was the worst for redbay due to laurel wilt disease – the annual mortality rate rose from 2.6% to 10.9% — slightly more than a four-fold increase. Almost as great an increase in mortality rates – to approximately three-fold – was found for ash trees attacked by the emerald ash borer (from 2.6% to 10.9%); beech dying from beech bark disease (from 0.7% to 2.1%); and hemlock killed by hemlock woolly adelgid, hemlock looper, and other pests (from 0.5% to 1.7%).

Some species are presumed to have an elevated mortality rate, but the pre-invasion “background” rate could not be calculated. These included American chestnut (mortality rate of 7%), butternut succumbing to butternut canker (mortality rate of 5.6%), and elm trees succumbing to “Dutch” elm disease (mortality rate of 3.5%).

The non-native pests and pathogens that have invaded the largest number of counties are white pine blister rust (955 counties), European gypsy moth (630 counties), dogwood anthracnose (609 counties in the East; the western counties were not calculated); emerald ash borer (479 counties); and hemlock woolly adelgid (432 counties).

The invaders posing the most widespread threat as measured by the volume of wood of host species are European gypsy moth (230.9 trillion ft3), Asian longhorned beetle (120.5 trillion ft3), balsam woolly adelgid (61 trillion ft3), sudden oak death (44.6 trillion ft3), and white pine blister rust (27.7 trillion ft3).

The proportion of the host volume invaded by these non-native pests is 94% for white pine blister rust, 48% for balsam wooly adelgid, 29% for European gypsy moth, 12% for sudden oak death, and one half of one percent for Asian longhorned beetle.

Of course, measuring impact by wood volume excludes some of the species suffering the greatest losses because the trees are small in stature. This applies particularly to redbay, but also dogwoods. Also, American chestnut was so depleted before FIA inventories began that it is also not included – despite the species’ wide natural range and large size.

[You can see the details for particular species by visiting the FIA “dashboards”. A particularly good example is that for hemlock woolly adelgid, available here.

USFS Response

Of course, the Forest Service has been trying to counter the impact of invasive insects and pathogens for decades, long before this study documented measurable changes in mortality rates.

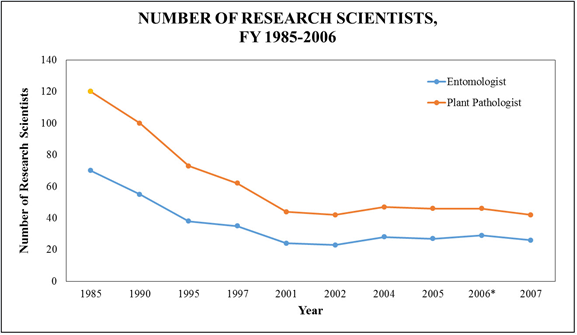

Unfortunately, funding for the agency’s response has been falling for decades – with concomitant reduction in staffs needed to carry out the work. See the graph below from p. 108 of my report, Fading Forests III, available here.

The President’s FY2020 budget proposes additional cuts.

The proposal would cut funding for the USFS Research division by $42.5 million (14%); cut staff by 212 staff years (12.5%). It would refocus the research program on inventory and monitoring; water and biological resources; forest and rangeland management issues, especially fire; forest products innovations; and people and the environment.

As shown by the above graph, this proposed cut follows years of loss of expertise and research capacity.

The President’s budget proposes to slash the State & Private Forestry account by 45.6% – from $335 million to just $182 million. The critically important Forest Health Management program is included under State & Private Forestry. The cuts proposed for FHM are 7% for work done on federal lands (from $44.9 million to $41.7 million; and 16% for work done on non-federal “cooperative” lands (from $38 million to $31.9 million). Staffing would be reduced by 4% for those working on federal lands, a startling 38% for those working on cooperative lands.

For details, view the USDA Forest Service budget justification, which can be found by entering into your favorite search engine “FY2020 USFS Budget”. Funding details begin on p. 12; staffing number details on p. 15.

These severe cuts are proposed despite the fact that the budget justification notes that pests (native as well as exotic) threaten more than four million acres and that those pests know no boundaries. The document claims that the Service continues to apply an “all lands” approach.

When considering individual invasive pest species, these proposed cuts exacerbate reductions in previous years. Some cuts are probably justified by changes in circumstances, such as improved understanding of a species’ life cycle resulting from past research. However, some are still troubling. (Again, for details, view the USDA Forest Service budget justification, which can be found by entering into your favorite search engine “FY2020 USFS Budget”. A table listing species-specific expenditures in recent years, and the proposed FY2020 levels, is on pp. 38-39.)

The budget proposes to eliminate spending to manage Port-Orford-cedar root disease – which was funded at just $20,000 in recent years but received $200,000 as recently as FY2016. Forest Health Management would cease funding restoration for whitebark pine pests, including white pine blister – despite widespread recognition of the ecological importance of this species. Research on blister rust would continue, but at just over half the funding of recent years. Spending on oak wilt disease would be cut by 45%; funding for protecting hemlocks by 40% (the latter received $3.5 million in FY16). Funding for management of sudden oak death is proposed to be cut by 31% . Cuts to these programs seem particularly odd given that much of the threat is on federal lands – the supposed priority of the Administration’s budget.

The budget calls for a 12% cut in funding for the emerald ash borer – at the very time that USDA APHIS plans to terminate its regulatory program and state agencies and conservationists are looking to the Forest Service to provide leadership.

According to Bob Rabaglia, entomologist for the Forest Health Management program, the proportion of the FHM budget allocated to invasive alien species (as distinct from native pests) has been rising in recent years. Some of this increase is handled through a new “emerging pest” account. Species targeted by these funds, I have been told, include beach leaf disease; goldspotted oak borer; and the invasive polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers.

Unfortunately, the “emerging pest” account funds are not included in the table on pp. 38-39 of the budget justification. Nor have I been able to learn from program staff how much money is in the fund and how much has been allocated to these or other pest or disease threats.

Adequate funding of the USFS Research and Forest Health Management programs could allow the agency to support, inter alia, efforts by agency and academic scientists to breed trees resistant to the damaging pest. I am aware, for example, of efforts to find “lingering” ash, beech, hemlock, whitebark pine, and possibly also redbay. None is adequately funded.

Please contact your member of Congress and Senators and urge them to support adequate funding for these two Forest Service programs. Research should be funded at $310 million (usually 5% or less of these funds is devoted to invasive species); Forest Health should be funded at $51 million for cooperative lands and $59 million for federal lands. It is particularly important to advocate for funding for the “cooperative lands” account since both the Administration and many members of Congress think the Forest Service should focus more narrowly on federal lands.

It is particularly important to contact your member if s/he is on the Interior Appropriations subcommittees. Those members are:

House:

- Betty McCollum, Chair (MN 4th)

- Chellie Pingree (ME 1st)

- Derek Kilmer (WA 6th)

- José Serrano (NY 15th)

- Mike Quigley (IL 5th)

- Bonnie Watson Coleman (NJ 12th)

- Brenda Lawrence (MI 14th)

- David Joyce, Ranking Member (OH 14th)

- Mike Simpson (ID 2nd)

- Chris Stewart (UT 2nd)

- Mark Amodei (NV 2nd)

Senate:

- Lisa Murkowski, Chair (AK)

- Lamar Alexander (TN)

- Roy Blunt (MO)

- Mitch McConnell (KY)

- Shelly Moore Capito (WV)

- Cindy Hyde-Smith (MS)

- Steve Daines (MT)

- Marco Rubio (FL)

- Tom Udall, Ranking (NM)

- Diane Feinstein (CA)

- Patrick Leahy (VT)

- Jack Reed (RI)

- Jon Tester (MT)

- Jeff Merkley (OR)

- Chris van Hollen (MD)

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.