For nearly 30 years I have documented bioinvasion threats and gaps, first in three Fading Forests reports (available here), then in five years of blogging. Here I pull together that information and suggest — in most cases reiterate — steps to address these threats and gaps. I list sources of discussion of the underlying issues – other than my reports and blogs – in references at the end of this blog.

My first premise is: robust federal leadership is crucial:

- The Constitution gives primacy to federal agencies in managing imports and interstate trade.

- Only a consistent approach can protect trees (and other plants) from non-native pests.

- Federal agencies have more resources than state agencies individually or in any likely collective effort — despite decades of budget and staffing cuts.

My second premise is: success depends on a continuing, long-term effort founded on institutional and financial commitments commensurate with the scale of the threat. This requires stable funding; guidance by research and expert staff; and engagement by non-governmental players and stakeholders. Unfortunately, as I discuss below, funding has not been adequate or stable.

My third premise is that programs’ effectiveness needs to be measured, not just effort (see the NECIS document referenced at the end of the blog).

SPECIFICS

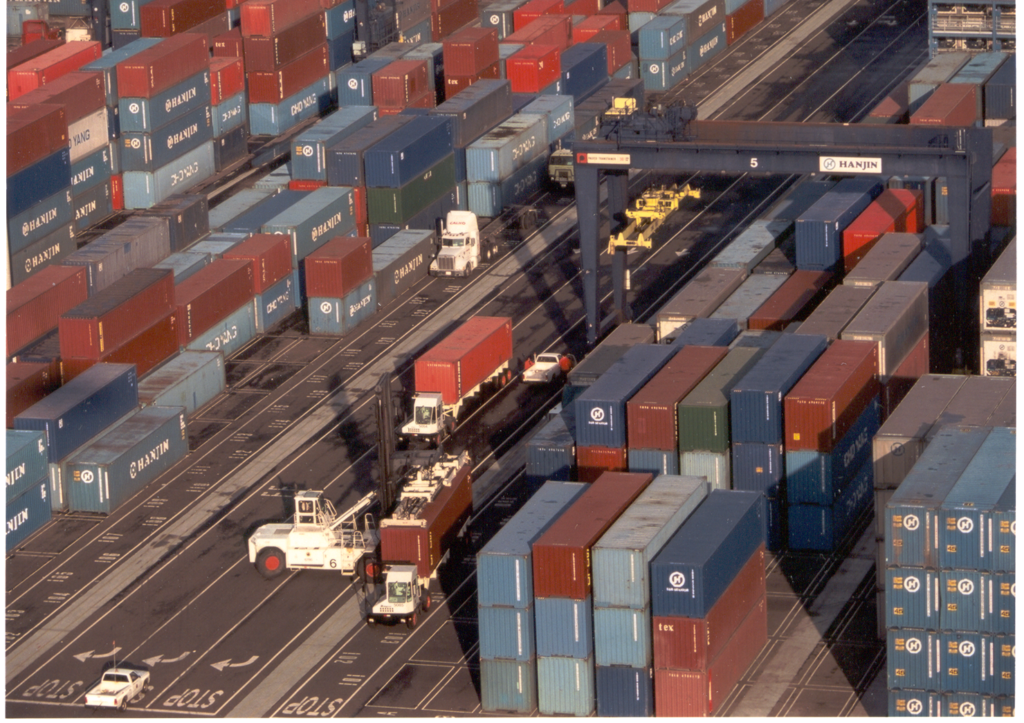

Preventing new introductions continues to be the most effective action. Mitigating options decrease and damages increase once a non-native pest has entered the country – much less become established (see Lovett et al. 2016 and Roy et al. 2014). I recognize that preventing new introductions poses an extremely difficult challenge given the volume and speed of international trade and the strong economic forces supporting free trade. These challenges have been exacerbated over several decades by the political zeitgeist – the anti-regulatory ideology, the emphasis on “collaborating” with “clients” rather than imposing requirements through regulations. Although the current “America First” policy might reduce import volumes and therefore reduce the invasive species threat to some extent, the anti-regulatory stance has only strengthened.

Decades of cutting key agencies’ budgets and personnel are another factor. However, the damage to America’s natural systems is so great that we must try harder to find more effective strategies (See the Fading Forest reports; my previous blogs; Lovett et al. 2016; and APHIS annual reports – e.g., the 2019 report here)

Prevention

- Despite adoption and implementation of new international and national regulations to stem pest introductions, introductions continue – although probably at a lower level than would otherwise be the case. Delays in adoption of regulations (documented in Fading Forests II and III and my two recent 30-years-in-review blogs have facilitated damaging introductions and spread.

Solutions

- Stakeholders press USDA leadership to initiate rules intended to strengthen phytosanitary protection and expedite their completion

- APHIS promote and facilitate analysis of current programs and policies by non-agency experts to ensure the agency is applying most effective strategies (Lovett et al. 2016).

- Adoption of insufficiently protective regulations (documented in FFII, FFIII, two 30-years-in-review blogs) – adopted in part because APHIS is trying to “balance” trade facilitation and phytosanitary protection – has further contributed to damaging pests’ introduction and spread.

Solutions:

- Boost priority of preventing pest introductions by amending the Congressional finding in the Plant Protection Act [7 USC 7701(3)] as follows

Existing language: “[I]t is the responsibility of the Secretary [of Agriculture] to facilitate exports, imports and interstate commerce in . . . commodities that pose a risk of harboring plant pests or noxious weeds in ways that will reduce, to the extent practicable, as determined by the Secretary, the risk of dissemination of plant pests and noxious weeds .… “

Amend to read as follows: “…. in ways that will reduce prevent, to the greatest extent practicable feasible, as determined by the Secretary, …” [emphasis added]

- Adopt several actions to strengthen phytosanitary protections at the point of origin (Lovett et al. 2016)

- Expand pre-clearance partnerships — as authorized for plants under Q-37 regulations and ISPM-36

- Expand sentinel tree programs

- Promote voluntary substitution of packaging made from materials other than solid wood.

- APHIS doesn’t use the enforcement powers that it has under Plant Protection Act (see several of my past blogs)

Solutions:

- APHIS follow the lead of Customs and Border Protection and begin penalizing importers on the first instance of their wood packaging not being in compliance with ISPM#15 (see blog here).

- APHIS prohibit use of wood packaging by countries and importers of categories of imports that – over the 13 years since implementation – have developed a record of frequent violations of ISPM#15.

- APHIS use its authority per revised Q-37 regulations to negotiate with countries that export plants to the U.S. to establish “integrated measures” programs aimed at minimizing the risk of associated pests being transported to the U.S.

- APHIS use its authority per revised Q-37 to place in the “Not Authorized for Import Pending Pest Risk Assessment (NAPPRA) “limbo” category genera containing North American “woody” plants (see Roy et al. 2014; Lovett et al. 2016).

Spread within the U.S.

- The United States lacks a coordinated system to prevent pest spread within the country (see Fading Forests III Chapter 5). Even our strictest methods, like APHIS’s quarantines regulating interstate movement of goods, have failed to curtail spread of significant pests. The most obvious example is the emerald ash borer.

The regulations governing movement of the sudden oak death pathogen in the nursery trade have also failed: there have been periodic outbreaks in which the pathogen has been spread to nurseries across the country. Between 2003 and 2011, a total of 464 nurseries located in 27 states tested positive for the pathogen, the majority as a result of shipments traced from infested wholesalers. In 2019, plants exposed to the pathogen were again shipped to 18 states; eight of those states have confirmed that their plant retailers received infected plants (see my blog from summer here).

Another serious gap is the frequent failure of APHIS and states to adopt official programs targetting bioinvaders that will be difficult to control because of biological characteristics or cryptic natures – even when severe impacts are demonstrated. Recent examples include the laurel wilt disease complex, goldspotted oak borer, polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers and associated pathogens, and even the spotted lanternfly (although the last has received significant funds from APHIS.)

Solutions:

- APHIS apply much more stringent regulations to interstate movement, based on a heightened priority for prevention in contrast to facilitating interstate trade. E.g., prohibit nurseries on the West Coast from shipping P. ramorum hosts to states where the pathogen is not established.

- APHIS encourage states to adopt quarantines and regulations aimed at preventing spread of invasive pests to regions of the state that are not yet infested. For example, the sudden oak death pathogen in California and Oregon; the borers in southern California.

- APHIS abandon plans to deregulate emerald ash borer and step up its support for state regulations on firewood.

- APHIS stop dumping pests it no longer wants to regulate onto the states through the “Federally Recognized State Manage Phytosanitary (FRSMP) program”.

- APHIS revise its policies so that the “special needs exemption” [7 U.S.C. 7756] actually allows states to adopt more stringent regulations to prevent introduction of APHIS-designated quarantine pests (see Fading Forests III Chapter 3).

To help fill the gaps, the states are trying to coordinate their regulations in some important areas. The most advanced example is the voluntary Systems Approach to Nursery Certification, or SANC program. APHIS has supported this initiative, including by funding from the Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Program (see below). However, it is a slow process; USDA funds first became available in 2010. The states are trying to coordinate on firewood, but we don’t yet know what the process will be.

- Funding shortfalls (See the three Fading Forests reports, my blogs about appropriations)

- Increase APHIS’ access to emergency funds from the Commodity Credit Corporation by amending the Plant Protection Act [7 U.S.C. 7772 (a)] to include this new definition of “emergency”:

the term “emergency” means any outbreak of a plant pest or noxious weed which directly or indirectly threatens any segment of the agricultural production of the United States and for which the then available appropriated funds are determined by the Secretary to be insufficient to timely achieve the arrest, control, eradication, or prevention of the spread of such plant pest or noxious weed.

- Although APHIS has the most robust prevention program of any federal agency, its funding is still inadequate. Stakeholders should lobby the Congress in support of higher annual appropriations.

The Plant Pest and Disease Management and Disaster Program (now under Section 7721 of the Plant Protection Act) has provided at least $77 million for tree-pest programs (excluding NORS-DUC & sentinel plant programs and other programs) since FY 2008. Much useful work has been carried out with these funds. However, these short-term grants cannot substitute for stable, long-term funding. I reiterate my call for stakeholders to lobby the Congress to provide larger appropriations to the APHIS Plant Protection program and Forest Service Forest Health Protection and Research programs.

Long-term Responses to Bioinvasive Challenge

More stakeholders are advocating raising the priority of – and providing adequate resources to – such long-term solutions as biocontrol and breeding trees resistant to pests and restoring them to our forests. Advocates include the state forestry agencies of the Northeast and Midwest, some non-governmental organizations, some academics, and individual USFS scientists. One effort resulted in inclusion of language in the 2018 Farm Bill (see blog here) – although this approach has apparently run into a dead end. The new emphasis on breeding has so far not been supported by agency or Congressional leaderships.

Solutions:

- USFS convene workshop of the federal, state, National Academy, academic, and NGO groups promoting resistance breeding in order to develop consensus on priorities and general structure of program.

Explicitly include evaluation of the CAPTURE Project’s (see blog here) efforts to set priorities to guide funding allocations and policies; and proposals for providing needed supportive infrastructure – facilities, trained staff in various disciplines. (See my blogs here.)

Report results of meeting to USDA leadership, Congress, and stakeholders

Then ensure implementation of the accepted approach by both Research and Development and Forest Health Protection programs. Include provisions to provide sustainable funding.

These proposed actions still do not address ways to correct the provisions of the international phytosanitary agreements (World Trade Organization and International Plant Protection Convention) that complicate – or preclude – efforts to prevent introduction of pests currently unknown to science. This issue is discussed in Fading Forests II. A current example is beech leaf disease (described here).

Continuing inadequate engagement by stakeholders

Most constituencies that Americans expect to protect our forests don’t press decision-makers to fix the problems I have identified above: inadequate resources, weak and tardy phytosanitary measures. Some of these stakeholders are other federal agencies, or state agencies – or their staffs. They face restrictions on how “political” they can be. But where are the professional and scientific associations, representatives of the wood products industry, forest landowners, environmental NGOs and their funders, urban tree advocates Efforts by me, USDA, and others to better engage these groups have had disappointing results.

As I have documented, groups of USFS scientists have made several attempts to document the extent of invasive species threats and impacts and to set priorities. So far, they have not gained much traction. Another USFS attempt, Poland et al. in press, will appear at the end of the year. Will this be more successful?

I detect growing attention to educating citizen scientists for early detection; but if there is an inadequate – or no – official response to their efforts won’t people become discouraged?

SOURCES

Lovett, G.M., M. Weiss, A.M. Liebhold, T.P. Holmes, B. Leung, K.F. Lambert, D.A. Orwig, F.T. Campbell, J. Rosenthal, D.G. McCullough, R. Wildova, M.P. Ayres, C.D. Canham, D.R. Foster, SL. Ladeau, and T. Weldy. 2016. NIS forest insects and pathogens in the US: Impacts and policy options. Ecological Applications, 26(5), 2016, pp. 1437–1455

National Environmental Coalition on Invasive Species “Tackling the Challenge.”

Poland, T.M., Patel-Weynand, T., Finch, D., Miniat, C. F., and Lopez, V. (Eds) (2019), Invasive Species in Forests and Grasslands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector. Springer Verlag. (in press).

Roy, B.A., H.M Alexander, J. Davidson, F.T Campbell, J.J Burdon, R. Sniezko, and C. Brasier. 2014. Increasing forest loss worldwide from P&Ps requires new trade regulations. Front Ecol Environ 2014; 12(8): 457–465