photo by David Coyle

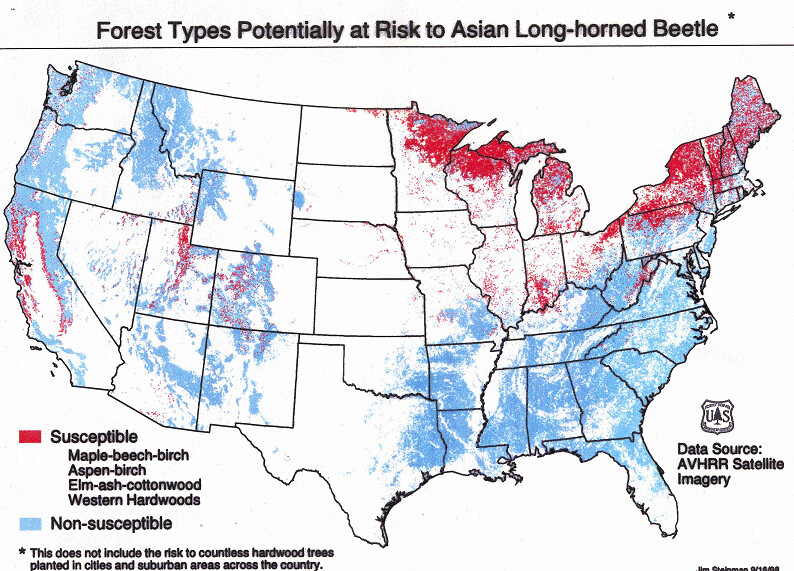

The Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) is one of the most threatening of the hundreds of non-native insects and pathogens introduced to American forests since European colonization began 400 years ago. The ALB attacks about 100 species of trees in 12 or 13 genera; it prefers maples, poplars, willows, and elms. Forests with substantial components of susceptible species constitute 10% of forests on the U.S. mainland and nearly all of Canada’s hardwoods. Host trees species also make up a significant proportion of trees in urban areas. A two-decade old estimate is that ALB could cause more than $1.2 billion in damage to urban trees [Coyle et al. 2021; full citation at the end of the blog]. The contemporary estimate would be higher.

The ALB began showing up in imports and in warehouses less than a dozen years after the U.S. opened trade with China [see Chapter 3 of Fading Forests II; url provided at the end of this blog]. Now there is a new infestation in South Carolina that threatens to be the most difficult to eradicate. Given the level of resources and extended commitment this will demand from APHIS and South Carolina, I worry that the agencies and Congress will give up. To find more money, will the agency take funds from other pests that also need to be addressed? Will it seek – and receive – emergency funding? Congress is currently considering funding for APHIS for the fiscal year that begins in October. Let’s inform them of the need to ensure adequate resources to carry forward necessary eradication efforts.

ALB in the U.S.: 25 Years of Repeated Infestations and Eradications

The first established ALB population to be detected was that in Brooklyn, New York, in 1996. Since then, seven more outbreaks have been detected in the United States [Poland et al. 2021; South Carolina press release] plus two in Canada. Several populations have been eradicated: a single population in Illinois, several populations in New Jersey, three populations in New York; a small outlying population in Ohio (APHIS newsletter Feb 2021); and two Canadian outbreaks.

Despite the U.S. and Canada having adopted regulations requiring treatment of wood packaging from China effective January 1999, ALB larvae continue to be detected in wood packaging from that country. Between 2012 and 2017, the ALB was intercepted six times in wood packaging made of Populus wood – each time originating from a single wood-treatment facility in China (Krishnankutty et al. 2020 – full citation at the end of the blog).

ALB Near Charleston, S.C.: Recently Detected; Must be Eradicated

The most recent detection is near Charleston, South Carolina. As usual, a beetle was found by a member of the public. Dendrological studies indicate that this infestation was seven years old at the time of its detection in May 2020, meaning it began about 2013 (Coyle et al. 2021). As the authors note, it has proved impossible to determine whether the South Carolina outbreak resulted from transport of infested wood from the Ohio outbreak or from China directly. Lots of visitors travel from the Midwest to South Carolina every winter. The center of the primary area of infestation includes a railway and an RV park which might be utilized by such travelers. On the other hand, two ports that receive high volumes of incoming shipping containers including wood packaging are nearby — Charleston, SC and Savannah, GA (Coyle et al. 2021). Charleston imported almost 666,000 containers (measured as 20-foot equivalents, or TEUs) in 2013.

Even under the best circumstances, eradicating an ALB infestation is difficult. Eradicating the Chicago outbreak took ten years [Poland et al. 2021]; eradicating the Brooklyn infestation took 23 years [APHIS ALB newsletter]. Massachusetts might be on the verge of eradicating the Worcester outbreak twelve years after it was detected because only one infested tree was found in 2020 [Felicia Hubacz at Northeast Forest Pest Council meeting, March 2021]

Eradication entails removing large numbers of trees – more than 171,000 in the Northeast and Midwest; and pesticide treatment of at least 800,000 [Poland et al. 2021]. Tens of thousands of trees must be inspected – especially in areas with significant woodland areas like the South Carolina site. In Clermont County, Ohio, 3,500,000 trees have been surveyed in the regulated area – which is 56 square miles [APHIS newsletter]

In South Carolina, APHIS and the state are already regulating 72.6 mi2 — and that is before the full extent of the infestation has been delimited. This regulated area is larger than the Ohio and New York regulated areas, although smaller than that in Massachusetts (110 mi2 Coyle et al.). As of February 2021, 4,425 infested trees have been identified (APHIS newsletter]. Ninety-eight percent are red maples; half of the others are willows (Coyle et al.) In May 2021, APHIS expanded the quarantine zone to 76.4 square miles (APHIS press release May 21, 2021).

So APHIS and South Carolina face a great deal of hard work. But acreage and numbers of trees affected don’t convey the real extent of the challenge.

The first challenge is anticipating the timing of events in the ALB life cycle. Scientists understand a great deal about the ALB life cycle. However, that knowledge all applies to areas with temperate climates such as the U.S. northeast, southern Canada, and Europe. South Carolina has a subtropical climate. How will the warmer climate affect the beetle’s speed of development, timing of emergence, etc. Already, dendrologial studies indicate that the ALB in South Carolina might complete development from egg to mature adult much faster – in less than a year rather than one to four years (Coyle et al.)

An even bigger challenge will be trying to carry out searches for infested trees and standard responses. Removing infested trees and removing or applying pesticides to at-risk host trees is standard practice. Much of the regulated area has standing water and/or saturated soil. These conditions – plus the presence of venomous snakes and alligators – make visual surveys from the ground or by tree climbers difficult. Use of lifts and bucket trucks will be impossible. When infested trees are found, felling trees in swampy conditions presents a heighted risk for felling crews. And it will be impossible to operate the equipment needed to remove or chip infested trees (Coyle et al.). I believe it is impossible to use soil injection to treat at-risk trees under such conditions.

SOURCES

Coyle, D.R., R.T. Trotter, M.S. Bean, and S.E. Pfister. 2021. First Recorded Asian Longhorned Beetle (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Infestation in the Southern United States. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, (2021) 12(1): 10; 1–6

Krishnankutty, S., H. Nadel, A.M. Taylor, M.C. Wiemann, Y. Wu, S.W. Lingafelter, S.W. Myers, and A.M. Ray. 2020b. Identification of Tree Genera Used in the Construction of Solid Wood-Packaging Materials That Arrived at U.S. Ports Infested With Live Wood-Boring Insects. Commodity Treatment and Quarantine Entomology

Poland, T.M., T. Patel-Weynand, D.M. Finch, C.F. Miniat, D.C. Hayes, V.M. Lopez. 2021. Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States. Springer.

USDA APHIS Asian longhorned beetle monthly newsletter for March 2021. Sign up here https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/asian-longhorned-beetle/ALB-eNewsletter

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm