Increasing frequency and severity of forest disturbances pose significant challenges to the sustainable management of forests in the West and to the goods and services they provide. A recent study (Barrett and Robertson 2021; full citation at end of blog) found that natural and human-caused disturbances affected 22.3% of forest land in the West over a 5-year period. The study analyzed fire, drought, insects, disease, invasive plants, their interactions, and their socioeconomic impacts. Climate change was found to affect most disturbance processes now and is expected to continue to do so in the future.

The impacts of these disturbances varied; most disturbances did not result in stand-replacing mortality.

Overarching Findings on Disturbance Agents in Western Forests

- Insect and disease outbreaks were the most extensive disturbance types. Each was estimated to affect 6.1 million hectares. Insect and disease outbreaks also caused the highest levels of tree mortality. This finding resulted from what was described as a relatively “low” threshold for “disturbance.” The authors set this threshold at disturbances that cause damage or mortality to 25% of trees in a stand or 50% of an individual tree species.

The overwhelmingly important causal agent was the mountain pine beetle (MPB; Dendroctonus ponderosae). Even after an approximately 50% drop in mortality after its peak years in the 2000s, MPB caused almost half the total area affected by all bark beetles combined 2000-2016.

The great majority of “pest” organisms causing disturbance in the West are native. Some non-native pests are important, though, and they are expected to become more important in the future. The most damaging non-native agent is white pine blister rust (WPBR; Cronaritum ribicola). Despite the largest control effort (in the 1930s), WPBR has caused drastic declines in white pines in the West. Currently attention focuses on high-elevation pines, especially whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), which is suffering extensive mortality from a combination of drought, MPB, and WPBR.

Other non-native pests discussed in the report are balsam woolly adelgid, larch casebearer, spruce aphid, and sudden oak death (SOD). The report notes the presence of a second strain of the causal agent of SOD (Phytophthora ramorum). In June 2021, a third strain was detected in Oregon forests (COMTF newsletter). There are mere mentions of goldspotted oak borer and polyphagous shot hole borer. The California fivespined ips (Ips paraconfusus) is reported to vector the fungus Fusarium circinatum which causes pitch canker disease in Monterey pine (Pinus radiata).

- The second most extensive disturbance agent in the West is human activity – silvicultural management and conversion to non-forest land uses. These activities affected 4.4 million ha.

- The third most extensive disturbance agent is grazing (primarily livestock). This affected 3.9 million ha.

- Fire thus ranks fourth as a disturbance agent – as measured by extent. During a five-year period ending in 2017 or 2018, fire affected 3.7 million ha. (I don’t know whether this ranking will change in response to the fire cataclysms of the most recent years; apparently the latest year included in the data was 2017.) The area affected by fire during this period was double that of the period 1960 to 2000. However, fire frequency and extent were still considerably lower than in the 1920s through1940s, before the advent of fire suppression, especially in the drier forests of the interior West.

- Other disturbance events – including those caused by weather and vegetation (presumably invasive plants) – affected far smaller areas: a total of 2.3 million ha.

Furthermore, drought and invasive plants – while increasing in extent & intensity – are often considered contributing factors rather than as proximate causes.

Data on past disturbance extents are poor for all these causes except fire. Analysis is further complicated by the high variability of disturbance events – year to year and across space. It is also often difficult to determine the ultimate causes. This makes the implications of these recent increases difficult to ascertain.

As the report points out, forest conditions are inherently dynamic, not stable. They note particularly human manipulation of fire – originally setting fires and then, more recently, suppressing them, has shaped the region’s forests for centuries. Fire suppression has significantly altered forest structure throughout the region, resulting in increasing fuel loads, decreasing resilience to fire and other disturbances.

Impacts of Climate Change

Fire suppression has also increased rates of carbon sequestration (see below).

The report notes that while past timber harvest, land clearing, insect outbreaks, and fires have reduced carbon stocks in forests across the United States to about half their maximum storage potential, recent vegetation and forest cover dynamics have resulted in net increases in carbon stocks in the West – despite CO2 emissions from trees killed by fire and insect damage since 2000.

In the future, climate change is expected to increase tree mortality substantially. In drier forests, mortality would result from increased fire incidence facilitated by a combination of longer fire season and decreased snowpack, reduced summer precipitation, and higher temperatures. In high-elevation and mesic forests, mortality would result from reduced snowpack, precipitation, and temperature.

About half of the West is likely to experience unprecedented climates by the end of this century. This change in climate could trigger changes in vegetation types and extent, net primary productivity, wildfire frequency, and expansion of the range of tree-damaging pests. Grasslands, chaparral, and montane forests are expected to expand; subalpine forests, tundra, and Great Basin woodlands are expected to contract.

Except in Arizona, California, and New Mexico, bark beetles are having a larger impact on forest CO2 emissions than is fire. Future impacts are unclear. Under moderate climate conditions forests would grow faster than under more severe scenarios, but they would thereby generate more fuel for the fires likely to occur during dry years. These fires might ultimately lead to lower carbon stocks.

I have addressed the invasive plant data in a separate blog.

Reducing Impacts via Management

Barrett and Robertson (2021) suggest management actions that could reduce the impact of these disturbances. First, they mention actions aimed at reducing invasions by non-native insects, pathogens, and plants. Also, they name actions to ameliorate climate change, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions or increasing carbon sequestration and storage to mitigate expected future damage from wildfire, drought, and beetles.

They recommended a series of on-the-ground management actions: fuel reduction treatments; thinning to reduce tree mortality from drought; favoring species that do not host specific pests; and planting genetically resistant varieties. They call for caution to prevent transport of pathogens to new areas during restoration planting of nursery stock or in “assisted migration” projects. Economic impacts of disturbance events on recreation could be mitigated by altering the timing and duration of recreational site visits. The authors also note that the best choices will differ both by site-specific factors and by management goals. They call for community education programs, cooperative stewardship across multiple agencies and landowners, and local and regional planning.

Details on Pest Impacts

Disease dominated in the high elevations of interior mountain ranges and in the precipitation-heavy regions of Oregon and Washington. Even in these locations, mortality levels are often low, resulting in multi-aged stands with complex structure. Patterns of disturbance are expected to change as pathogens and their hosts adapt to climate change. The microbes might evolve more rapidly than the host trees.

Sudden oak death (SOD) is now the leading biotic cause of tree mortality in coastal forests of California [and possibly Oregon?]. In heavily infested areas SOD has caused conversion of previously tanoak-dominated stands. The report provides a summary of Oregon’s attempts to eradicate SOD from 2001 to 2012.

I am surprised by the failure to mention non-native pest impacts on two narrowly endemic species: Port-Orford cedar root disease and pitch canker disease in Monterrey pines – other than to mention the vector (above).

Insect outbreaks were most common in pine forests. Decades of fire suppression, and now climate change, have substantially altered forest conditions over millions of hectares, primarily increasing the density of shade-tolerant and fire-intolerant trees (e.g., true firs, Abies spp.). Balsam woolly adelgid (BWA; Adelges piceae) is now threatening subalpine fir stands in British Columbia, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Utah. BWA is ranked as the 10th most damaging forest insect, first among non-native species over the next few decades (2013-2027). The spruce aphid (Elatobium abietinum) is having its most significant impact in coastal Southeast Alaska on Sitka spruce and in Arizona on Engelmann spruce. Projected increases in temperature and the frequency of droughts in the West will likely make spruce aphid a more significant disturbance agent in coming decades.

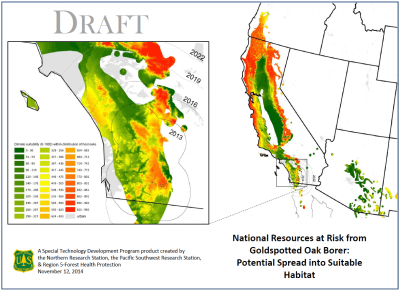

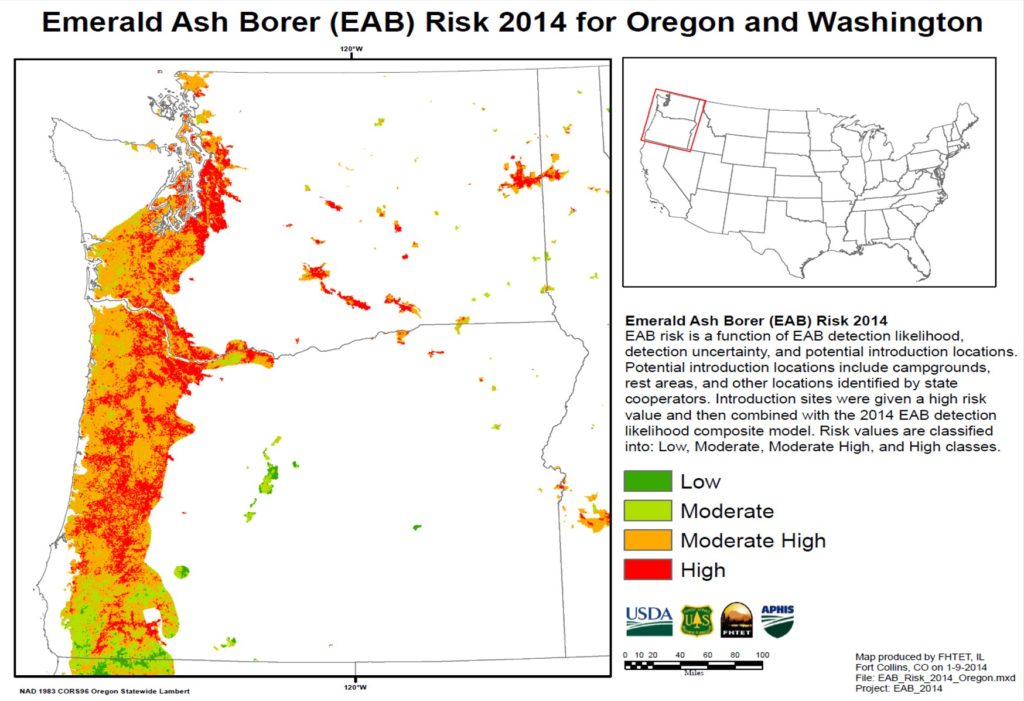

In discussing the goldspotted oak borer (GSOB; Agrilus coxalis sic) in California and emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis) in Colorado, Barrett and Robertson (2021) say that the heterogeneity of western landscapes provides some buffer against invasion. However, I note that GSOB threatens oaks throughout California (see the map at left). EAB threatens riparian areas of the Pacific states (see map below). These riparian areas are admittedly small in geographic extent but ecologically vital.

Barrett and Robertson (2021) expect seven tree species to suffer substantial levels of tree mortality in the near future. Six are pines threatened in large part by mountain pine beetle, led by the two high-elevation five-needle pines, whitebark pine (58% of total basal area) and limber pine (44%). These are followed by lodgepole pine (39%), ponderosa pine (28%), pinyon pine (27%), Jeffrey pine (26%). The seventh is grand fir (25% of total basal area); the report does not specify which agents are responsible.

Data Issues

The report notes that insects and pathogens are only partially covered by existing monitoring programs. Pathogens are particularly hard to detect and to make conclusive attributions of causality.

SOURCE

Barrett, T.M. and G.C. Robertson, Editors. 2021. Disturbance and Sustainability in Forests of the Western United States. USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-992. March 2021

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm