This blog summarizes important new research on invasive plant species. You’ll find a USFS update on the spread of invasive plants in regional forests. The second paper used a new funding source to assess the impacts of removing invasive shrub honeysuckles on forest canopies – and to begin restoration. The third paper uses Google searches to study news coverage of plant invaders (spoiler alert: it’s poor). I welcome the attention!

A. Update on Invasive Plants in the Northeast: 44 Species, in 24 States, on Forested Land

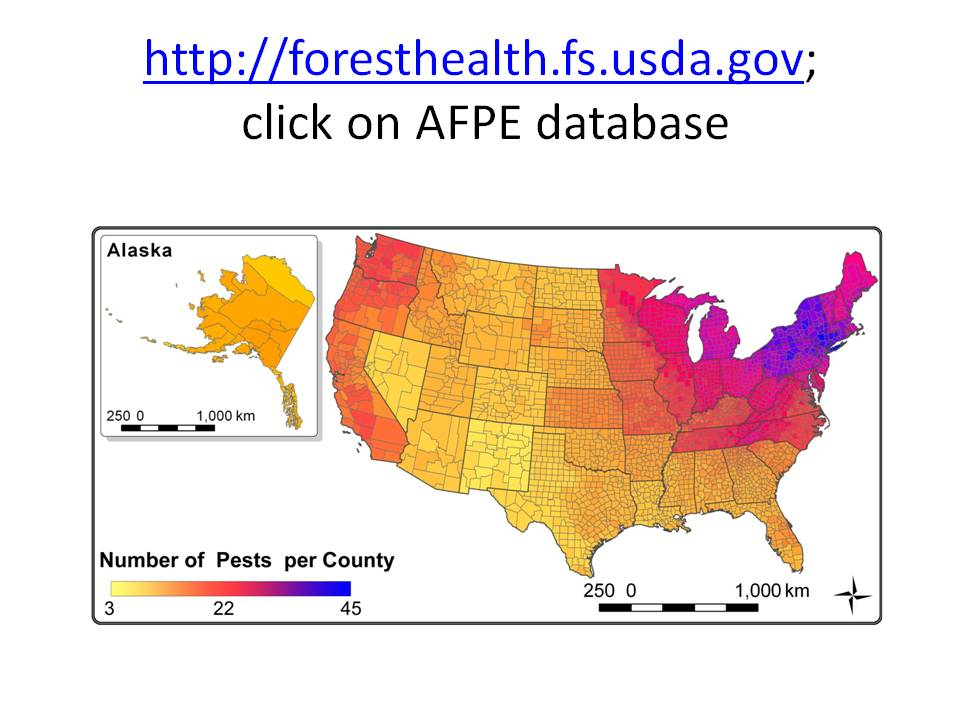

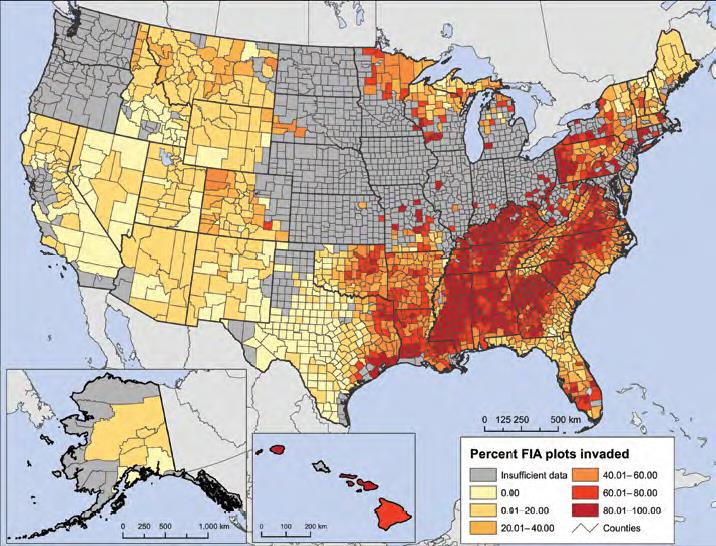

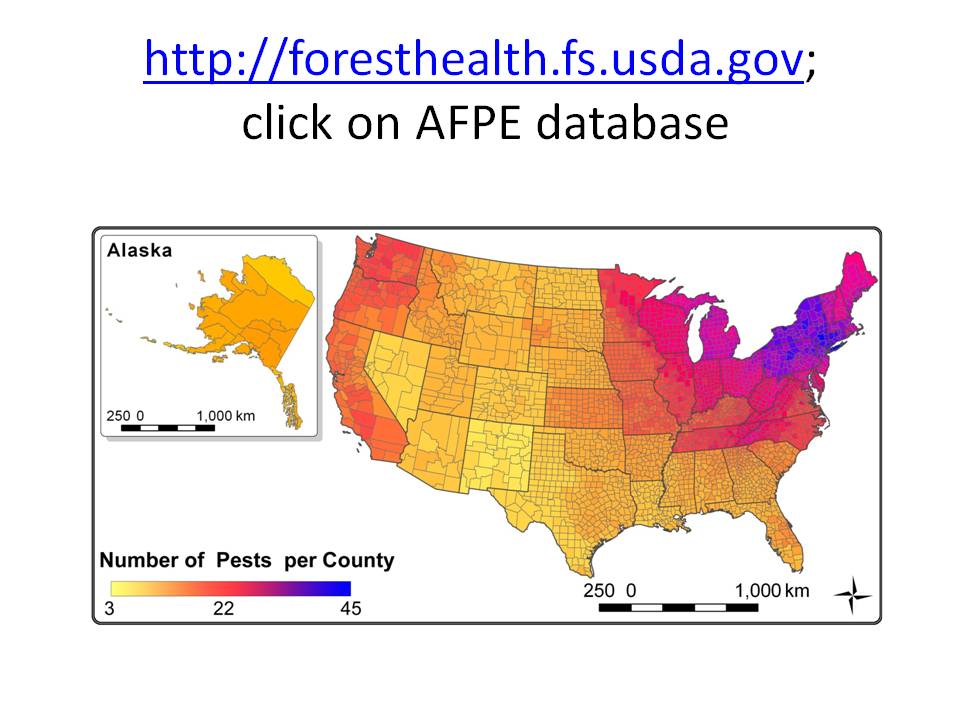

The USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station (NRS) continues to publish lots of studies of invasive plants in the forests of the Northeast and Midwest. Kurtz (see USDA citation at end of blog) summarizes data on the extent and intensity of plant invasions collected by the USFS Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program. Since 2012, scientists have compiled data on 44 invasive species on forested land. Crews recorded these plants’ presence on 6,361 plots in 2014 and 4,244 in 2019. [The species surveyed are listed in Table 2 of the publication.]

1. Presence —

Overall, the number of forested plots on which one or more of the 44 monitored invasive species occurs rose from 52% in 2014 to 55% in 2019. Eighteen of the 24 states in the region experienced an increase in the percentage of plots with invasive plants. The number of invasive plants per plot also increased.

The plots with the greatest number of these invasive plants are Ohio (98%), Indiana (97%), North Dakota (93%), and Illinois and Iowa (92% each). The North Dakota data bear a high uncertainty because only 15 plots were surveyed in 2019. The states with the lowest number of invaded plots are New Hampshire (16%) and Vermont (22%). South Dakota also ranks near the bottom with 38% of plots invaded.

A different picture emerges when considering the number of invasive plants per plot. States ranking highest on this criterion were Pennsylvania (13 species on at least one plot) and Illinois (11 species on at least one plot). (See map in USDA publication from References) Plots with five to eight species appear in a band from the Ohio/West Virginia border, across western Maryland and western and eastern Pennsylvania, and into western New York and western Massachusetts. Note the apparent abse nce of invasive plants in the Adirondacks!

2. Species

Of the 44 species monitored, 41 species were observed on plots during these surveys. Two of the three species not found — punktree/Melaleuca and Chinese tallow tree (Triadica sebifera) – grow in the deep South so I am not surprised by their absence. The third – Bohemian knotweed (Polygonum xbohemicum) is invasive in colder climates, e.g., Washington State. Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) is the most common species – again, not surprising since it was long planted deliberately to provide food for wildlife. Three species were observed in one but not both inventories: Chinaberry (Melia azedarach) was only found in 2014; saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) and European swallow-wort (Cynanchum rossicum) were found only in 2019.

Most of the 44 plant species increased their presence as measured by the proportion of plots on which they were observed (see Table 2). Among these, Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) increased by 5.38%; garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) by 3.21%; Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) by 2.95%; and bush honeysuckles (Lonicera species.) by 2.77%. Twelve species decreased – all by less than one percent.

3. One of the Worst: Amur Honeysuckle

Amur honeysuckle is one of most actively spreading invasive plant in the entire region – especially in urban forests. The proportion of plots invaded by this species rose from half a percent to six percent between 2014 and 2019. Amur honeysuckle dominates due to competitive growth, allelopathy (producing a biochemical that impedes the germination, growth, and survival of other plants), and its ability to resprout after cutting. The presence of honeysuckle negatively affects native plant communities. It suppresses plant recruitment, homogenizes forest communities, and alters ecosystem processes. It also shapes the canopy structure by affecting the growth and composition of overstory trees, as well as the amount of leaf material (Fotis et al.).

The riparian areas which Amur honeysuckle often invades provide numerous ecosystem services. These include filtering nutrients, preventing soil erosion, filtering sediment from runoff, offering shade and wildlife habitat, and reducing the likelihood of floods to croplands and downstream communities (Fotis et al.).

B. Managing Honeysuckle, Restoring Riparian Forests

Forest managers in central Ohio, near Columbus, have begun a significant restoration experiment to improve the resilience and function of disturbed riparian forests. Fotis and colleagues took advantage of this to track and characterize the immediate, short-term, and long-term impacts of removing Amur honeysuckle on forest canopies. They used new technology: portable canopy imaging, detection, and ranging (LiDAR).

Fotis et al. found that

- Honeysuckle presence had a stronger influence on tree species diversity than on the size or number of trees.

- Removing honeysuckle from areas where its abundance is high and native tree density is low promoted native tree growth (e.g., the height of tallest trees) and increases in the tree canopy’s structural complexity for up to 10 years.

- Honeysuckle removal, followed by treating honeysuckle stumps with herbicides to prevent resprouting, is key for establishing a healthy restored riparian forest.

- Planting a diverse suite of native species to fill different ecological niches helps create more resilient forest systems.

- Forest recovery began within two years of honeysuckle removal.

At some sites, the researchers planted a variety of woody plants, including understory shrubs and mid- and full-canopy trees, after removing the honeysuckle. The article did not discuss the results.

C. Poor Media Coverage of Invasive Plants Undermines Management Efforts

Woodworth et al. (full citation at end of blog) studied how media coverage of invasive plants interacts with low public interest, which the authors claim hampers management efforts and efficacy.

Woodworth et al. note that strong public awareness of urgent environmental issues is linked to the development of new public policy. However, public awareness of invasive species is low despite their causing high monetary costs and significant damage to the environment and human health.

The authors recognize the public generally has a low level of “plant awareness”. They argue that some plants are “charismatic” in one way or another, e.g., some form widespread and conspicuous monocultures; some are attractive and sold in the ornamental trade; and some are harmful to people by producing allergens or bearing thorns/spines/prickles. Such plants often attract more attention.

They asked four questions: Is public interest in these invasive plant species driven by (1) their abundance? (2) their traits? (3) the quantity and sentiment of news articles written about them? Finally, (4) How do these factors combine to drive interest – or lack thereof! – in invasive plant species?

1. Searching for Answers

Woodworth et al. analyzed data on Google searches (in Google Trends) for 209 plant species, 2010 – 2020. The searches revealed whether members of the public sought information about invasive plants, whether news media covered invasive plant issues, whether such coverage had a positive or negative slant, and whether it affected public awareness and attitudes toward invasive plants.

They found that public search interest was highest for the species that are most abundant at both national and state levels. Plant abundance was the second strongest predictor of Google search interest. Also, the more widespread the invader, the more articles were published and the more negative the terms used to describe it. For some species, high search interest was limited to the locations where the plant occurs. An example is garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). For other species, there was high search interest across the US although the plant occurs only in some localities. This was true, for example, for giant hog-weed (Heracleum mantegazzianum).

In a related finding, plant species posing a risk to human health ranked high in Google searches. These include giant hogweed (which causes serious skin rashes), allergen-producing grasses, plants that harbor ticks, and those that contribute to fires in the West like cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum). Regarding ticks, they cite multiflora rose but not barberry (Berberis spp). These results suggest to the authors that public interest in invasive plants is motivated primarily by the likelihood of encountering these species, with direct consequences for health and well-being. These concerns can be amplified by the media. The authors suggest that articles spelling out health risks of invasive plants might increase public support for wider management efforts.

The greater the number of articles published about a species, the more frequently readers utilized Google to search for information. Woodworth et al. suggest that more attention by the media translates to more public interest. They caution, however, that there are two other possible explanations. First, more searches might drive science journalists [I add: or newspaper editors!] to write more articles on species already known to be of interest to the public. Or, search and media interest might be unrelated to each other, but driven by the same external factors, such as a recent fire. In other words, journalists and the general public might be interested in the same aspects of invasive plants.

2. Which Invaders Got Attention

The media and public focus on only some invasive plants. Media articles discussed only 175 (84%) of the 209 species included in the study. More than 50% of news articles were written about only 10 species (5% of all the species); 80% on just the top 25 species. Public interest was even narrower. No one searched for information on 60 of the species (29%) over the 10-year period.

The authors – and I – are distressed that invasive plants that are sold as ornamentals were both written about and searched for less than invasive plants that are not so marketed. Worse, articles about the ornamental species had a more positive tone than articles about non-marketed invasives.

Finally, they found that species that form monocultures did not garner more media attention, more negative coverage, or search interest. Their example is Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), which they describe as being a problematic and prolific invader of eastern forest understories. There are exceptions to this finding: common reed Phragmites and kudzu. I note that these species are very noticeable, and thus “charismatic.” The former is a large plant and masses along roadsides and in open habitats. Kudzu has been notorious for decades as the “vine that ate the South”.

Woodworth et al. concluded that the media’s narrow focus on “notorious” invasive plant species, when combined with the lower and more positive coverage of ornamental introductions, could send mixed messages and weaken public awareness of their threats. The authors believe, however, that there is ample opportunity to improve messaging and increase public awareness. This requires more media coverage and a greater focus on invasive plants’ negative impacts. One potentially “sticky” message is about “loss of control.”

SOURCES

Fotis, A., Flower, C.E.; Atkins, J.W. Pinchot, C.C., Rodewald, A.D., Matthews, S. 2022. The short-term and long-term effects of honeysuckle removal on canopy structure and implications for urban forest management. Forest Ecology and Management. 517(6): 120251. 10 p. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120251 .

USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station Rooted in Research ISSUE 18 | SEPTEMBER 2023

Kurtz, C.M. 2023. An assessment of invasive plant species in northern U.S. forests. Res. Note NRS-311. http://doi.org/10.2737/NRS-RN-311

Woodworth, E. A. Tian, K. Blair, J. Pullen, J.S. Lefcheck and J.D. Parker. 2023. Media myopia distorts public interest in US invasive plants. Biol Invasions (2023) 25:3193–3205 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03101-8

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or