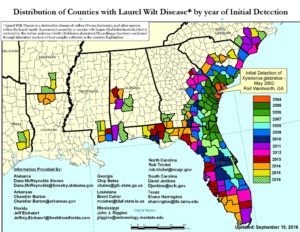

Spread of laurel wilt since 2003; source: USFS

Redbay mortality, Claxton, GA 2009

Redbay mortality, Claxton, GA 2009

photo by Scott Cameron

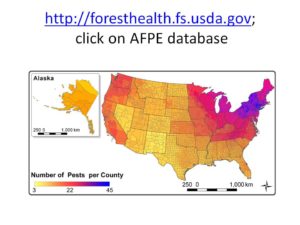

The southeastern states have been invaded by a smaller number of non-native, tree-killing insects and pathogens than some other regions (see map below). But among these are highly damaging pests that show just how vulnerable this area’s native species and forests are, e.g., chestnut blight, laurel wilt, hemlock woolly adelgid, balsam woolly adelgid, and now emerald ash borer (all described here).

Join the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases at its annual meeting in Savannah, GA, November 9 & 10, 2017 to learn about the issues outlined below and to build relationships to sustain action. The meeting will be in conjunction with the Annual Gypsy Moth Review, so we will also discuss the most recent developments pertaining to European and Asian gypsy moths. Visit www.continentalforestdialogue.org to see the agenda and registration information (both to be posted soon).

The Southeast is at high risk for greater damage because:

- The Port of Savannah is already the largest container port on the East Coast. Now, it moves 20,000 shipping containers per day and it is adding infrastructure to increase this volume.

Most of these containers – and their accompanying wood packaging material (for more on the risk from wood packaging, see my blog from the end of January; and fact sheets here) quickly move to distribution centers or their ultimate destinations – throughout the Southeast but as far away as Chicago. However, the port has storage for millions of containers on paved container yards that total 1,200 acres. The storage yards are close to mixed forests.

Trees across road from stored containers at Port of Savannah; photo by F.T. Campbell

More of these ships and containers will come directly from Asia – the major source of our most damaging invaders — now that the Panama Canal has been widened. When I visited the port in mid-May, the largest container ship ever to visit the U.S. East Coast was being unloaded – and re-loaded simultaneously! The “Cosco Development” carries 13,200 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent containers).

Unloading “Cosco Development” at Port of Savannah; photo F.T. Campbell

- The sudden oak death pathogen (Phytophthora ramorum) has been found in streams and ponds in several southeastern states – Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. Positive samples were drawn from three streams in Alabama and one stream in Mississippi in 2016. Most of these water bodies are near nurseries that had received infested plants from West Coast suppliers. In addition, infested plants have been detected recently in nurseries or landscape plantings in Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia, as well as in other states farther north [link to 2015 blog]. These infested plants have been removed. What is the current scientific thinking about the implications of these detections? Last I heard, scientists thought the pathogen cannot survive in water; it needs some plant material. Yet scientists have not found on-going infestations on plants along the streams and ponds. For more information on SOD, visit http://www.suddenoakdeath.org/

- Over recent decades, a half dozen non-native insects that attack pine trees have become established in the continental United States. These include the Sirex woodwasp, common pine shoot beetle, golden (or red) haired pine bark beetle (Hylurgus ligniperda), Mediterranean pine shoot beetle (Orthotomicus erosus) — all described here. The mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) has spread east of the Rocky Mountains and might eventually reach pine forests of the Midwest and East.

While none of these (other than the mountain pine beetle) has yet caused very much damage where they are established, should we continue to assume that they will not cause damage once they reach the “pine basket” of the Southeast? Even if plantations can be managed to minimize risk, what are the implications for natural pine forests so important to the ecosystems and protected areas of the region?

It is unclear whether the fact that the Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, is a former governor of Georgia with a record of support for forestry will raise attention to some of these issues. As you might remember (see my blog from March 28th), apparently no senators raised invasive pest issues during Secretary Perdue’s confirmation.

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.