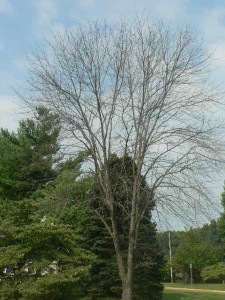

Several analyses seek to quantify the risk that new tree-killing pests will be introduced to North America. They use different data sources and assumptions, and reach somewhat different conclusions. But all agree that the risk remains high, and the consequences of such introductions are dire.

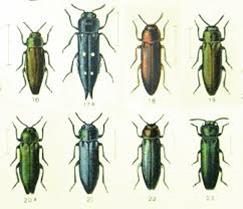

I have relied on the Aukema et al. 2010 (see references at the end of the blog) and Haack et al. 2014 studies in past blogs. Aukema et al. 2010 looked at the probable dates of introduction for established insects and pathogens to determine that over 150 years, from 1860 to 2006, damaging forest insect and pathogen species were detected at an average rate of between 0.47 and 0.51 species per year. This translates to one damaging insect or pathogen every 2.1 to 2.4 years. The frequency of detection of high-impact forest pests rose sharply after 1990; beginning that year, detections of high-impact forest pests averaged 1.2 per year, nearly three times the rate of detections in the previous 130 years.

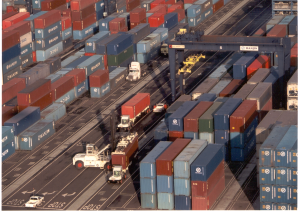

In 2013, 25 million shipping containers entered the U.S. An estimate from more than a decade ago is that wood packaging is used in about half of these containers. Haack et al. (2014) has estimated that 0.1% (1/10th of 1%) of the wood packaging in more than 12 million shipping containers entering the country each year is infested with quarantine pests. That works out to nearly 13,000 containers harboring pests that probably enter the country each year. That is 35 potential pest arrivals per day.

Leung et al. 2014 concluded that continuing to implement the international standard — ISPM#15 — at the efficacy level described by Haack et al. would result in a tripling of the number of non-native wood-boring insects introduced into the U.S. by 2050.

Koch et al. 2011 have also attempted to determine the current rate of introduction of wood-boring insects. They also sought to evaluate the introduction risk for specific metropolitan areas.

Koch et al. utilized various sources of information about volumes of imports of goods likely to be associated with wood-boring pests (e.g., raw wood and wood products; and stone, metals, non-metalic minerals, auto parts, etc., contained in wooden crates and pallets) to estimate both a nationwide establishment rate of wood-boring forest insect species and the likelihood that such insects might establish at more than 3,000 urban areas in the contiguous US.

They estimated the nationwide rate of introduction of wood-boring pests at between 0.6 and 1.89 forest pest species per year for the period 2001–2010. Even the more conservative estimates points to establishment of a new alien forest insect species somewhere in the US every 2–3 years. If one accepts the ‘‘tens rule’’ – that one out of ten new introductions proves to have substantial effects, then one expects establishment of a significant new pest on average every 5 – 6 years. The authors note that the establishment of at least four ecologically and/or economically significant alien forest insects during the past 20–25 years – emerald ash borer, Asian longhorned beetle, Sirex woodwasp, and redbay ambrosia beetle – fits the model’s conclusion. [All of these pests are described in the Gallery of Pests posted here.]

The Aukema et al. estimate for introductions of “high impact” pests during the period after 1990 – 1.2 per year – is in the middle of the Koch et al. estimate for wood-borers, but higher than the Koch et al. estimate for “significant” pests.

Koch et al. estimated a lower rate of introductions between 2010 and 2020 – between 0.36 and 1.7 species per year. The Haack et al. and Leung et al. analyses would seem to contradict this expectation. Also, the findings of Seebens et al. (see my blog from earlier this week) contradicts any expectation that introductions will soon decline as a result of depletion of the pool of possible pests in origin countries.

Koch et al. analyzed data on imports of relevant commodities from all source regions to determine the introduction risk for 3,126 urban areas in the country. The urban area at greatest risk was Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana, California. The predicted introduction rate for both 2010 and 2020 for this metropolis was establishment of a new alien forest insect species every 4–5 years. The port of New York-Newark came in second, with a predicted establishment rate of one every 8–9 years. Houston ranked third; its predicted establishment rate was one every 13–15 years. All other urban areas were at substantially lower risk – a new introduction every 24 years.

Looking ahead to the decade 2010 to 2020, Koch et al. found that three California metro areas – Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana; San Diego; and Riverside-San Bernardino – would be exposed to increased establishment rates driven by the growth of imports from Asia.

Risk To Canada

Yemshanof et al. 2011 applied the Koch et al. methodology to evaluate the risk to Canada. Reflecting the lower volume of imports entering Canada compared to the U.S., they found a lower nationwide entry rate for Canada – 0.338 new forest insect species per year vs. the Koch et al. estimate of 1.89 for the U.S. Evaluating individual urban areas, they found the greatest risks to the Greater Toronto and Greater Vancouver areas. Moderate-sized cities near ports, major markets, or U.S.-Canada border crossings – transportation hubs – were also at heightened risks.

Canada as Pest Pathway to U.S.

Yemshanof et al.’s model indicates that 8% of all tree pests entering the U.S. as estimated by Koch et al., come through goods transshipped through Canada. The risk is highest to the Pacific Coast states since they are the most likely to receive Asian goods transiting through Canada. Note that the U.S. and Canada have proposed requiring that wood packaging originating in one of the countries and shipped to the other should be included under the ISPM#15 regulation. However, APHIS was unable to adopt this regulation under the Obama Administration, and such an action seems even less likely under the Trump Administration.

Neither study included plant imports, which are another very important pathway for introduction of tree-killing pests, especially pathogens.

SOURCES

Haack RA, Britton KO, Brockerhoff EG, Cavey JF, Garrett LJ, et al. (2014) Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Koch, F.H., D. Yemshanov, M. Colunga-Garcia, R.D. Magarey, W.D. Smith. 2011. Potential establishment of alien-invasive forest insect species in the United States: where and how many? Biol Invasions (2011) 13:969–985

Leung, B., M.R. Springborn, J.A. Turner, E.G. Brockerhoff. 2014. Pathway-level risk analysis: the net present value of an invasive species policy in the US. The Ecological Society of America. Frontiers of Ecology.org

Yemshanov, D., F.H. Koch, M. Ducey, K. Koehler. 2012. Trade-associated pathways of alien forest insect entries in Canada. Biol Invasions (2012) 14:797–812

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org

Japanese honeysuckle; courtesy of Bugwood.org