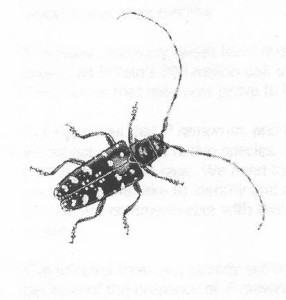

polyphagous shot hole borer exit holes on box elder; photo source http://ucanr.edu/

I have posted many blogs criticizing California state authorities for not acting to counter several highly damaging tree-killing pests, such as the goldspotted oak borer and invasive shot hole borers.

I should have made it clear that many Californians – academics, employees of local, state, and federal agencies, concerned citizens – are working very hard to develop scientific knowledge, test strategies, educate stakeholders and those whose activities facilitate the insects’ spread. These people have carried forward a wide range of dedicated efforts that do much to make up for the lack of state or federal agencies’ engagement.

More than 60 stakeholder entities now participate in one or more of nine working groups focused on shot hole borers, promoting research, education and outreach. Some of these activities receive advice (but apparently no funding) from California Department of Food and Agriculture. Outreach to the media has resulted in some good coverage. Master Gardeners and other potential citizen scientist groups have been trained. See here.

A smaller but older group is carrying out similar activities targetting goldspotted oak borer; visit here.

Here I summarize some of the most recent activities.

1) Scientists have released a pocket-sized guide for identifying trees infested by polyphagous or Kuroshio shot hole borers (For summaries of the threat posed by these insects and their associated fungi, visit here). The guide can be downloaded here.

The Guide is useful for people outside as well as inside California, since some host species grow across the continent: box elder (Acer negundo), sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), mimosa or silk tree (Albizia julibrissin).

Other hosts are common in horticulture: camellia (Camellia semiserrata), Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), Japanese wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), London plane (Platanus x acerifolia), mimosa, and weeping willow (Salix babylonica).

The shot hole borers could be present outside the six California counties known to contain infestations because one or both of these beetles could have been spread via movement of wood, greenwaste, or nursery stock; or they could have entered other parts of the country on plants or wood from Asia.

2) Scientists are testing possible pesticide treatments to protect trees from polyphagous shot hole borer

The polyphagous shot hole borer (a still undescribed beetle in the Euwallacea genus), attacks more than 200 host tree species in southern California, including many important native and urban landscape trees. Forty-nine species from more than 20 families are known to be reproductive hosts. Trees are dying in parks, residential neighborhoods, other public landscapes, and riparian areas. John Boland of Southwest Wetlands Interpretive Association has documented that 88% of the willows in the Tijuana River Valley have been infested by the Kuroshio shot hole borer – although many of the trees regrow into four-foot-tall shrubs. Dr. Boland estimates that more than two billion KSHB hatched in the valley during 2015-2016.

Confronted by such threats, home owners, park managers, and arborists are desperate for management tools.

As reported by Jones et al. 2017 (see reference below), scientists tested the effectiveness of insecticides, fungicides, and insecticide–fungicide combinations for controlling continued PSHB attacks on previously infested California sycamore trees. The combination of a systemic insecticide (emamectin benzoate), a contact insecticide (bifenthrin), and a fungicide (metconazole) provided the best control over the six months of the study period. The biological fungicide Bacillus subtilis provided short-term control.

Efficacy of the treatment combination is not yet settled. First, the polyphagous shot hole borer actively oviposits year-round, and both adults and larvae may be found in an infested tree at any time of year. Furthermore, the shot hole borers are active throughout the sapwood, not just in the phloem and cambium tissues. These differences in behavior may make timing and efficacy of systemic insecticides more difficult to predict. In addition, it is extremely difficult to detect infestations at an early stage, when treatment is most likely to be effective. Finally, the treated trees should be monitored over several years, rather than for six months, to evaluate true efficacy.

3) Efforts to gain official actions re: Invasive Shot Hole Borers

Some people are trying to promote state engagement. They are focused on getting adoption of a strategy under the auspices of the California Invasive Species Council to create a system to respond to bioinvaders that don’t fall within the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s definition of its responsibilities – e.g., the shot hole borers. The invasive shot hole borers are included in the interagency “Charting the Pest Prevention System in California” plan.

4) On-the-Ground Efforts

Some entities are compiling and publicizing their costs for responding to the several wood borers. For example, the University of California Irvine reports spending close to $2 million to manage trees on campus that have been attacked. The Orange County parks agency has spent $1.7 million on shot hole borer surveys, tree inventory, public outreach materials, staff training, and some research. These costs are rising – in the first half of 2017, Orange County parks agency has already spent $348,000 on tree treatment and removal.

UC Cooperative Extension for San Diego County organized a Green Waste-Wood Biomass Symposium in February aimed at educating industry and public agency waste-management practitioner.

Goldspotted Oak Borer

Three National forests are treating high-value oaks in specific sites:

- Cleveland NF sprayed 248 oak trees with the contact insecticide, carbaryl. The Forest hopes to continue the treatments yearly dependent on funding and need.

- The Angeles NF removed 50 GSOB-infected oaks in Green Valley. They then tagged about 1,000 oak trees in the area so their changing conditions can be monitored.

- San Bernardino NF is felling and debarking GSOB-infested oaks on the periphery of the communities of Idyllwild and Pine Cove.

Orange County removed highly infested trees at Weir Canyon; now spraying another 1,672 oaks, including both lightly infested and neighboring trees, with carbaryl … monitoring has not detected any other infested trees in Weir Canyon or neighboring Blind Canyon.

Summarized from the San Diego County update (reference below).

In the absence of legal mechanisms to stop the movement of infested firewood, collaborating organizations have focused on public education and outreach programs for the firewood industry, tree care professionals, and the public. Still, some infested wood continues to be moved – probably to uninfested areas.

The Update also reports the following impacts of the goldspotted oak borer in San Diego County:

- Eight San Diego County Parks have suffered loss of habitat, diminished recreational value, and direct costs associated with tree removal and grinding and insecticidal treatments. More than 5,000 trees have been lost in just one park, William Heise Park.

- One California State Park lost nearly $500,000 in campground and day-use fees when areas were closed for tree removal. GSOB has been discovered at two more State parks in recent years.

- The Cleveland National Forest has suffered negative environmental, economic and aesthetic impacts; removed more than 200 trees and treated 248 high-value trees on developed sites.

- Tribal lands have lost oaks of great cultural value as well as reduced habitat, shade, and recreational enjoyment.

- Urban and rural residential homeowners are faced with removal and disposal costs averaging $1,500 per tree.

- Fire, transportation, and public works agencies are dealing with higher fuel loads and hazard trees along rights of way.

GSOB activists are collaborating with those working on the invasive shot hole borers to seek state and federal support.

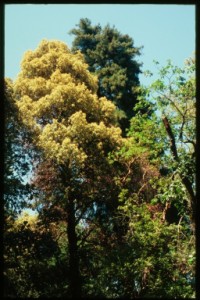

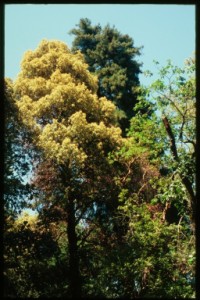

SOD-infected tanoak; photo by F.T. Campbell

SOD-infected tanoak; photo by F.T. Campbell

UPDATE ON SUDDEN OAK DEATH

Eight California nurseries were found late this spring to be infected by the sudden oak death pathogen (Phytophthora ramorum). (As of May, only two nurseries were known to be positive.) Seven of the positive nurseries are located in counties with disease in the natural environment. Given the wet winter and spring in California, this upswing is probably not surprising. Still, this sudden upsurge raises questions about the efficacy of nursery regulations. One of the nurseries was detected as a result of a trace-back investigation – not through the annual inspection.

SOURCES

California Oak Mortality Task Force newsletter, July 2017

Goldspotted Oak Borer and Oak Mortality Quarterly Situation Report April 1 through June 30, 2017

Status of Goldspotted Oak Borer – July 2017 Update Goldspotted Oak Borer Steering Committee www.GSOB.org Email: gsobinfo@ucdavis.edu

Invasive Shot Hole Borer (Polyphagous and Kuroshio)/Fusarium Dieback Quarterly Situation Report January 1 through March 31, 2017

Jones, M.E., J. Kabashima, A. Eskalen, M. Dimson, J.S. Mayorquin, J.D. Carrillo, C.C. Hanlon, and T.D. Paine. 2017. Evaluations of Insecticides and Fungicides for Reducing Attack Rates of a new invasive ambrosia beetle (Euwallacea Sp., Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Infested Landscape Trees in Calif. Journal of Economic Entomology, 110(4), 2017, 1611–1618 doi: 10.1093/jee/tox163 Advance Access Publication Date: 5 July 2017

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

Posted by Faith Campbell