It is widely recognized that invasions of non-native species occur as a consequence of international trade (see Seebens et. al. 2017 – full citations at the end of this blog). This is as true for non-native forest pests as for any other bioinvader – see Aukema et al. 2010; Liebhold et al. 2012, Lovett et al. 2016. In fact, gross domestic product – as an indicator of levels of trade — is a better predictor of the number of forest pest invasions in a given country than the country’s amount of forested land (Roy et al. 2014).

As I noted in my previous blog, I began studying and writing about the threat to North America’s forests from non-native insects and pathogens in the early 1990s. I reported my analyses of the evolving threat in the three “Fading Forests” reports – coauthored by Scott Schlarbaum – in 1994, 2003, and 2014. These reports are available here.

I document here that both introduction and spread of pests within the country have continued apace. While significant efforts have been made to prevent introductions (described briefly under the “Invasives 101” tab of the CISP website), they have fallen short. As I noted in Fading Forests III, programs aimed at preventing spread of pests within the country remain fragmented and often are unsuccessful.

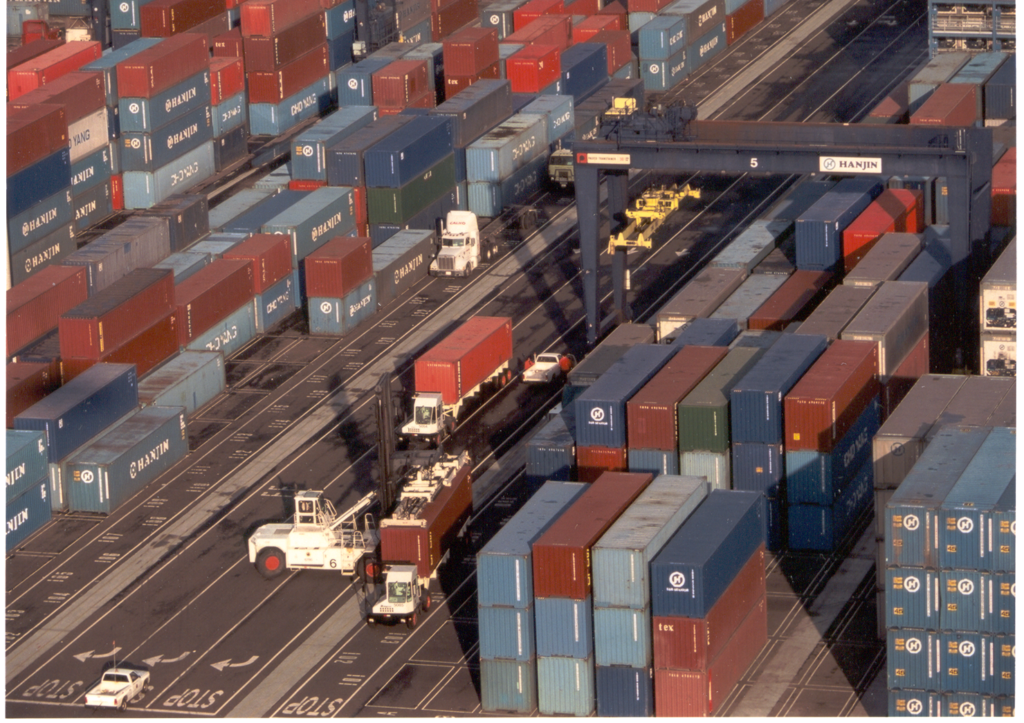

The Challenge: Huge Volumes of goods are moving, providing opportunities for pests

Since 1990, volumes of imported goods more than quintupled. Within the U.S., a total of 17,978 million tons of goods were transported in 2015; 10,776 million tons of this total by truck. About one-third of this total – 5,800 million tons – was moved farther than 250 miles. These vehicles moved on a public roads network of 4,154,727 miles (US DOT FFA). Consequently, once a pest enters the U.S., it can be moved quickly into every corner of the country.

Introductions

By and large, establishment of tree-killing pests has occurred at a fairly steady rate of about 2.5 per year, with “high-impact” insects and pathogens accumulating at 0.43 per year (Aukema et al. 2010). Since introductions did not rise commensurately with rising import volumes, Lovett et al. (2016) concluded that the recently adopted policies for preventing introductions referenced above are having positive effects but are insufficient to reduce the influx of pests in the face of ever-growing global trade volumes. The study’s authors went on to say that absent more effective policies, they expect the continued increase in trade will bring many new establishments of non-native forest pests.

One group of forest pests did not enter at a steady rate, but rather entered at a higher rate since 1985 – wood-boring insects. Experts concluded that the increase probably reflected increases in containerized shipping (Lovett et al. 2016). At the global level, the rate of fungal invasions has also recently been reported to be increasing rapidly (Roy et al. 2014).

Geography of trade patterns also matters. Opening of trade with China (in 1979) offered opportunities for pests from a new source country which has a similar climate and biology. Roy et al. describe the importance of phylogenetic relatedness of pests and of tree hosts in explaining tree species’ vulnerability to introduced pests. The most vulnerable forests are those made up of species similar to those growing in the source of the traded goods – i.e., the temperate forests of the northeastern U.S. – when goods are imported from similar forested areas of Europe and Asia. Chinese-origin wood-boring pests began to be detected around 1990. This already short interval probably underestimates how quickly pests began arriving; detection methods were poor in those years, so a pest was often present for close to a decade before detection.

Between 1980 and 2016, at least 30 non-native species of wood- or bark-boring insects in the Scolytinae / Scolytidae were newly detected in the United States (Haack and Rabaglia 2013; Rabaglia et al. 2019). Over the same period, approximately 20 additional tree pests were introduced to the continental states (Wu et al. 2017; Digirolomo et al. 2019; R. Haack, pers. comm.) plus about seven to America’s Pacific islands. Not all of the new species are highly damaging, but enough are. See my previous blog here.

Many of the tree-killing pests were probably associated with pathways other than wood packaging. These include 6 of the 7 Agrilus species, sudden oak death pathogen, three pests of palm trees, the spotted lanternfly, beech leaf disease; and the pests introduced to America’s Pacific Islands.

HIGH-RISK PATHWAYS OF INTRODUCTION

Already in the 1990’s it was evident that better preventing pest introductions would depend on shutting down the variety of pathways by which they move around the world. At that time, attention focused on imports of logs and nursery stock (nursery stock makes up one component of a broader category called by phytosanitary agencies “plants for planting”). Both logs and “plants for planting” had well-established histories of transporting pests and import volumes were expected to grow. We have since learned that there are many more pathways!

Plants for Planting

Imports of “plants for planting” (phytosanitary agencies’ term, which encompasses nursery stock, roots, bulbs, seeds, and other plant parts that can be planted) have long been recognized as a dangerous pathway for introduction of forest pests. For example, this risk was the rationale for adopting the 1912 Plant Quarantine Act. Charles Marlatt, Chairman of USDA’s Federal Horticultural Board (see “Then and Now” in Fading Forests III here), wrote about the risk in National Geographic in April 1911 (urging adoption of the 1912 law) and again in August 1921. See also Brasier (2008), Roy et al. (2014), Liebhold et al. (2012), Jung et al. (2016).

January 28, 1910; Agriculture Research Service

Of the 91 most damaging non-native forest pest species in the U.S. (Guo et al. 2019), about 62% are thought to have entered North America with imports of live plants. These include nearly all the sap-feeding insects, almost 90% of the foliage-feeding insects, and approximately half of the pathogens introduced during the period 1860-2006 (Liebhold et al. 2012). Specific examples include chestnut blight, white pine blister rust, Port-Orford-cedar root disease, balsam woolly adelgid, hemlock woolly adelgid, beech scale, butternut canker, dogwood anthracnose, and sudden oak death. In more recent years, introductions via this pathway possibly include ‘ōhi‘a rust, rapid ‘ōhi‘a death pathogens, and beech leaf disease. The gypsy moth, while a foliage feeder, was not introduced via imports of live plants.

The APHIS annual report for 2018 reported that in that year we imported 18,502 shipments containing more than 1.7 billion plant units (plants, bulbs, in vitro materials, etc.).

Liebhold et al. 2012, relying on 2009 data, found that about 12 percent of incoming plant shipments had symptoms of pests – a rate more than 100 times greater than that for wood packaging. Worse, a high percentage of the pests associated with a shipment of plants is not detected by the federal inspectors. The meaning of this finding is unclear because the study did not include any plant genera native to temperate North America and APHIS points out that infestation rates varied considerably among genera in the study. However, APHIS has not conducted its own analysis to document the “slippage rate” on imports of greatest concern to forest conservationists, i.e., imports of woody plants. I provide details on pests detected on imports of woody plants in recent in my blog here.

Clearly the risk of pest introductions continued at least until recently. I reviewed an APHIS database listing pests newly detected in the country during the period 2009-2013. I concluded that approximately 37 of the 90 “new” pests listed in the database (viruses, fungi, aphids and scales, whiteflies, mites) were probably introduced via imports of plants, cuttings, or cut foliage or flowers. I discussed these matters in greater detail here.

Adoption of a new regulatory regime governing imported plants for planting (Q-37 regulation) in 2018 is too recent to for us to see its impact. But the new regulation sets up a process under which APHIS can impose more protective regulations on specific types of plants or plants from certain countries of origin to counter a perceived concerning level of risk. Until APHIS begins activating its new powers by negotiating more protective regulations governing plant imports from high-risk sources, it seems unlikely there will be any meaningful change in the introduction rates.

Crates, Pallets, and Other Forms of wood packaging (solid wood packaging, or SWPM)

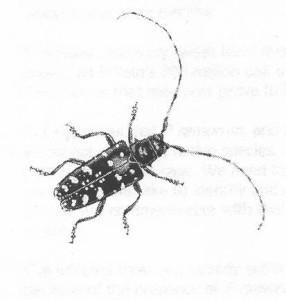

Recognition of the risk associated with wood packaging is much more recent. In 1982, a USDA risk assessment concluded that the wood boring insects found in crates and pallets were not of great concern (USDA APHIS and Forest Service, 2000). However, contradictory indications were quickly documented – including from APHIS’ own port interception data – which the agency began collecting in 1985. Over the 16-year period 1985-2000, 72% of the 6,825 bark beetles (Scolytidae) intercepted by APHIS were found on SWPM (Haack 2002). Cerambycids (longhorned beetles) and buprestids (jewel beetles) make up nearly 30% of insects detected in wood packaging over the last 30 years (Haack et al. 2014).

Detection of outbreaks of the Asian longhorned beetle and other woodborers in the mid-1990s made it clear that wood packaging was, indeed, a high-risk pathway.

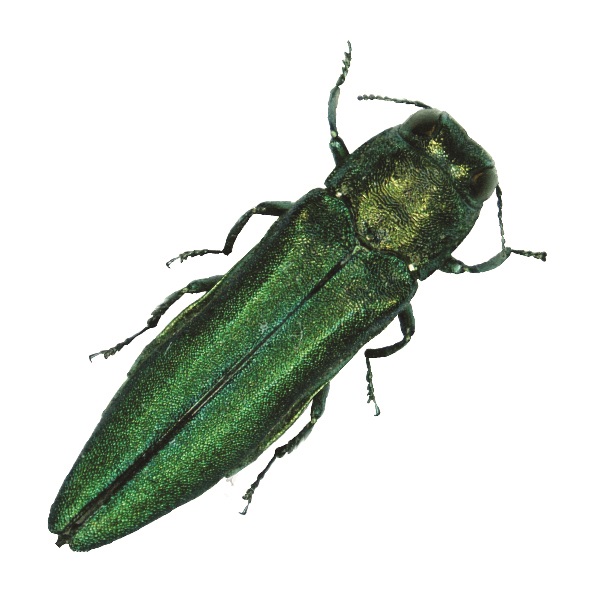

Of the 91 most damaging non-native pest species in the US, 30% probably arrived with wood packaging material or other wood products (Liebhold et al. 2012). This group includes many of the most damaging pests, the deadly woodborers – Asian longhorned beetle, emerald ash borer, redbay ambrosia beetle, possibly the polyphagous and Kuroshio shot hole borers.

As noted above, introductions of wood borers have risen in recent decades, widely accepted as associated with the rapid increase in containerized shipping after 1980. In 2009 it was estimated that 75% of maritime shipments were packaged in crates or pallets made of wood (Meissner et al. 2009). A good history of the global adoption of containerized shipping is Levinson, M. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton University Press 2008)

The simultaneous opening of trade with China (in 1979) offered opportunities for pests from a new source country which has a similar climate and biology. Chinese-origin wood-boring pests began to be detected around 1990. This already short interval probably underestimates how quickly pests began arriving; detection methods were poor in those years, so a pest was often present for close to a decade before detection.

I have already documented numerous times that, despite the U.S.’ implementation of the International Standard of Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) #15 in 2006, live quarantine pest woodborers continue to enter the U.S. in wood packaging. The best estimate is that 0.1% of wood packaging entering the United States is infested with wood-borers considered to be quarantine pests (Haack et al. 2014). More than 22 million shipping containers entered the U.S. via maritime trade in 2017 (US DoT). As noted, an estimated 75% of sea-borne containers include wood packaging. Applying the 0.1% estimate to these figures results in an estimate that as many as 17,650 containers per year (or 48 per day) transporting tree-killing insects enter the U.S.

Over a period of nine years – Fiscal Years 2010 through 2018 – U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) detected more than 28,600 shipments with wood packaging that did not comply with ISPM#15 (Harriger presentations to the annual meetings of the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases). While most of the non-compliant shipments were wood packaging that lacked the required mark showing treatment per ISPM#15, in 9,500 cases the wood packaging actually harbored a pest in a regulated taxonomic group.

Disturbingly, 97% of the shipments that U.S. CBP found with infested wood packaging bear the ISPM#15 mark certifying that wood had been fumigated or heat-treated (Harriger 2017). CBP inspectors tend to blame this on widespread fraud in use of the mark. On the other hand, one study found that larvae can survive both treatments – although the frequency of survival was not determined. It was documented that twice as many larvae reared from wood treated by methyl bromide fumigation survived to adulthood than larvae reared from heat-treated wood; the reason is unclear (Nadel et al. 2016).

The APHIS’ record of interceptions for the period FYs 2011 – 2016 contained 2,547 records for insect detections on wood packaging. The insects belonged to more than 20 families. Families with the highest numbers of detections were Cerambycids – 25% of total; Curculionidae – 23% (includes Dendroctonus, Ips, Orthotomicus, Scolytinae, Xyleborus, Euwallacea); Scolytidae – 17% (includes true weevils such as elm bark beetles); Buprestids – 11%; and Bostrichidae – 3%. Not all of the insects in these groups pose a threat to North American plant species.

One encouraging data point is that since 2010, there have been no detections of species of bark and ambrosia beetles new to North America in the traps deployed by the USDA Forest Service Early Detection and Rapid Response program (Rabaglia 2019). The 2014 recognition of the Kuroshio shothole borer apparently did not result from this trapping program.

There have been several changes in the wood packaging standard and its implementation by CBP since 2009, the year Haack et al. 2014 analyzed the “pest approach rate”. APHIS has not carried out a study to determine whether these recent changes have reduced the approach rate below Haack’s estimate of 0.01%. Consequently, we do not know whether these changes have reduced the risk of pest introductions.

Other Pathways That Transport Fewer Pests – Some of Which Have High Impacts

Insects that attach egg masses to hard surfaces can be transported by ship superstructures, containers, and hardsided cargoes such as cars, steel beams, and stone. While relatively few species have been moved in this way, some have serious impacts. The principal examples are the gypsy moths from Asia, which feed on 500 species of plants (Gibbon 1992).

The United States and Canada have a joint program – under the auspices of the North American Plant Protection Organization (see RSPM #33) aimed at preventing introduction of species of Asian gypsy moths. The NAPPO standard originally went into force in March 2012. Under its terms, ships leaving ports in those countries during gypsy moth flight season must be inspected and cleaned before starting their voyage.

Gypsy moth populations rise and fall periodically; it is much more likely that egg masses will be attached to ships during years of high moth population densities. These variations are seen in U.S. and Canadian detection reports – as reported here.

While most AGM detections are at West Coast ports, [here; and here] the risk is not limited to that region. AGM have been detected at Wilmington, NC; Baltimore, MD; Charleston, SC; Savanna and Brunswick, GA; Jacksonville, FL; New Orleans, LA; Houston and Corpus Christi, TX; and even McAlester, OK.

Nor is the risk limited to the ships themselves. In 2014, more than 500 Asian gypsy moth egg masses were found on four shipments of imported steel slabs arriving at ports on the Columbia River in Washington.

Between 1991 and 2014, AGM was detected and eradicated on at least 20 occasions in locations across the United States (USDA AGM pest alert). Additional outbreaks have been discovered and eradication efforts undertaken in more recent years.

A second example is the spotted lanternfly (SLF) (Lycorma delicatula), which was first detected in southeast Pennsylvania in autumn 2014. It is native to Asia; it is believed to have entered the country as egg masses on imported stone.

While SLF is clearly a pest of agriculture – especially grapes and tree fruits – its importance as a forest pest is still unclear. Many native forest trees appear to be hosts during the insect’s early stages, including maples, birches, hickories, dogwoods, beech, ash, walnuts, tulip tree, tupelo, sycamore, poplar, oaks, willows, sassafras, basswood, and elms. Adult lanternflies strongly prefer the widespread invasive species tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima).

As of August 2019, SLF was established in parts of five states: Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. It was detected as having spread to a 14th county in Pennsylvania; five new counties in New Jersey. APHIS is working with state departments of Agriculture in these states, as well as supporting surveys in New York, North Carolina, and West Virginia (USDA APHIS DA-2019-20, August 7, 2019). Apparently the detections of a few adults – alive or dead – in Connecticut and New York had not evolved into an outbreak. See description and map here.

Imports of logs – roundwood – seem inherently risky. Certainly Dutch elm disease was introduced via this pathway. However, there have been few pest introductions linked to this pathway in recent years, probably because we import most of our unprocessed lumber from Canada. (I provide considerable data on U.S. roundwood imports in Fading Forests III here.)

Decorative items and furniture made of unprocessed wood certainly have the potential to transport significant pests (USDA APHIS 2007). Examples include boxes and baskets; wood carvings; birdhouses; artificial Christmas trees or other plants; trellises; lawn furniture. To date, apparently, no high-impact pest has been introduced via this pathway, although pests intercepted on shipments have included Cerambycids from Asia, e.g., velvet longhorned beetle and here.

Alarmed by high numbers of infested shipments from China, APHIS first suspended imports of such items temporarily; then adopted a regulation (finalized in March 2012 – USDA APHIS 2012).

APHIS has not taken action to prevent introductions on such items imported from other countries – although the North American Plant Protection Action adopted a regional standard making the case for such action and outlining a risk-based approach (NAPPO RSPM#38).

Snails on Shipping Containers

Snails have been detected on shipping containers and wood packaging for decades. In 2015, APHIS stepped up its efforts to address this risk through bilateral negotiations with Italy and launching regional and international efforts to develop guidance for ensuring pest-free status of shipping containers (Wendy Beltz, APHIS, presentation to National Plant Board, 2018 annual meeting).

SPREAD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES

Major pathways for human-assisted spread of pests within the country are sales of plants for planting, movement of unprocessed wood – especially firewood, and hitchhiking on transport vehicles. Since most forest pests are not subject to federal quarantine, any regulatory programs aimed at preventing spread depend on cooperation among the 50 states. None of these pathways is regulated adequately to prevent pests’ spread. See Chapter 5 of Fading Forests III here.

And since neither federal nor state agencies do significant enforcement of existing regulations, preventing spread often depends upon pest awareness of, and voluntary compliance by, individuals and companies.

Even pests subject to a federal quarantine are not prevented from spreading. Plants exposed to the sudden oak death pathogen were shipped to 18 states in spring 2019.

A collaborative effort by the nursery industry, APHIS, and states (Systems Approach to Nursery Certification, or SANC) is striving to close gaps linked to the standard practice of inspecting plants at the time of shipping, but full implementation of this voluntary program is still years away.

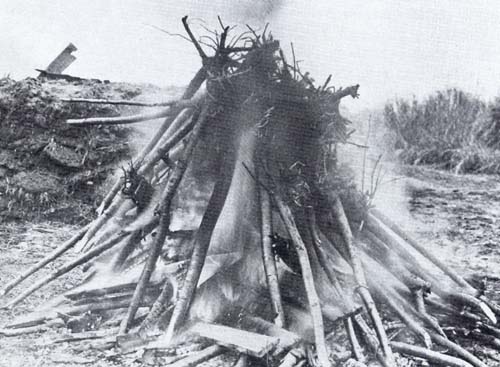

Transport of firewood has been responsible for movement of pests both short distances, e.g., goldspotted oak borer in southern California; and long distances – e.g., emerald ash borer to Colorado. APHIS attempted to develop a certification program but the industry was unable to put one together (see Chapter 5 of Fading Forests III). Current federal and state regulations of firewood are tied to the emerald ash borer quarantine, which APHIS has proposed to terminate. Wood for turning and woodworking has also been linked to movement of pests, e.g., walnut twig beetle/thousand cankers disease from the west to Pennsylvania.

Truck transport of a variety of goods has transported European gypsy moths from the infested areas in the east to the west coast. Transport of stone probably moved spotted lanternfly from southeastern Pennsylvania to Winchester, Virginia.

SOURCES

Aukema, J.E., D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle, A.M. Liebhold, K. Britton, & S.J. Frankel. 2010. Historical Accumulation of Nonindigenous Forest Pests in the Continental United States. Bioscience. December 2010 / Vol. 60 No. 11

Brasier, C.M. 2008. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology (2008) 57, 792-808

Bray, A.M., L.S. Bauer, T.M. Poland, R.A. Haack, A.I. Cognato, J.J. Smith. 2011. Genetic analysis of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) populations in Asia and North America. Biol. Invasions (2011) 13:2869-2887

Gibbon, A. 1992. “Asian Gypsy Moth Jumps Ship to United States.” Science. Vol. 235. January 31, 1992.

Guo, Q., S. Feib, K.M. Potter, A.M. Liebhold, and J. Wenf. 2019. Tree diversity regulates forest pest invasion. PNAS. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1821039116

Haack R. A. and J.F. Cavey. 1997. Insects Intercepted on Wood Articles at United States Ports-of-Entry and Two Recent Introductions: Anoplophora glabripennis and Tomicus piniperda. In press in International forest insect workshop proceedings, 18 – 21 August 1997, Pucon, Chile. Corporacion National Forestal, Santiago, Chile.

Haack, R.A., F. Herard, J. Sun, J.J. Turgeon. 2010. Managing Invasive Populations of Asian Longhorned Beetle and Citrus Longhorned Beetle:A Worldwide Perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010. 55:521-46.

Haack, R.A. and R.J. Rabaglia. 2013. Exotic Bark and Ambrosia Beetles in the USA: Potential and Current Invaders. CAB International 2013. Potential Invasive Pests of Agricultural Crops (ed. J. Peña)

Haack R.A., Britton K.O., Brockerhoff, E.G., Cavey, J.F., Garrett., L.J., 2014. Effectiveness of the International Phytosanitary Standard ISPM No. 15 on Reducing Wood Borer Infestation Rates in Wood Packaging Material Entering the United States. PLoS ONE 9(5): e96611. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096611

Haack, R.A., F. H´erard, J. Sun, and J.J. Turgeon. 2010. Managing Invasive Populations of Asian Longhorned Beetle and Citrus Longhorned Beetle: A Worldwide Perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010. 55:521–46

Harriger, K. Department of Homeland Security Bureau of Customs and Border Protection, presentation to the Continental Dialogue on Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases, November 2017.

Jung T, Orlikowski L, Henricot B, et al. 2016. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. Forest Pathology 46: 134–163.

Liebhold, A.M., E.G. Brockerhoff, L.J. Garrett, J.L.Parke, and K.O Britton. 2012. Live plant inports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US. Frontiers in Ecology.

Lovett, G.M., M. Weiss, A.M. Liebhold, T.P. Holmes, B. Leung, K.F. Lambert, D.A. Orwig, F.T. Campbell, J. Rosenthal, D.G. McCullough, R. Wildova, M.P. Ayers, C.D. Canham, D.R. Foster, S.L. LaDeau, and T. Weldy. 2016. Non-native forest insects and pathogens in the United States: Impacts and policy options. Eological Applications, 26(5) pp. 1437-1455.

Meissner, H., A. Lemay, C. Bertone, K. Schwartzburg, L. Ferguson, and L. Newton. 2009. EVALUATION OF PATHWAYS FOR EXOTIC PLANT PEST MOVEMENT INTO AND WITHIN THE GREATER CARIBBEAN REGION. Caribbean Invasive Species Working Group (CISWG) and Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory (PERAL) / CPHST. June 4, 2009

Morin, R. presentation at Northeastern Forest Pest Council 81st Annual Meeting, March 12 – 14, 2019, West Chester, Pennsylvania

Nadel, N., S. Myers, J. Molongoski, Y. Wu, S. Linafelter, A. Ray S. Krishnankutty, and A. Taylor. 2016. Identificantion of Port Interceptions in Wood Packaging Material: Cumulative Progress Report, April 2012 – August 2016

North American Plant Protection Organization Regional Standard for Phytosanitary Measures#24 https://www.nappo.org/english/products/regional-standards/regional-phytosanitary-standards-rspms/rspm-24/

North American Plant Protection Organization Regional Standard for Phytosanitary Measures#38 https://www.nappo.org/english/products/regional-standards/regional-phytosanitary-standards-rspms/rspm-38/

Rabaglia, R.J., A.I. Cognato, E. R. Hoebeke, C.W. Johnson, J.R. LaBonte, M.E. Carter, and J.J. Vlach. 2019. Early Detection and Rapid Response. A Ten-Year Summary of the USDA Forest Service Program of Surveillance for Non-Native Bark and Ambrosia Beetles. American Entomologist Volume 65, Number 1

Roy, B.A., H.M. Alexander, J. Davidson, F.T. Campbell, J.J. Burdon, R. Sniezko, and C. Brasier. 2014. Frontiers in Ecology 12(8): 457-465

Seebens et. al. 2017. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species world wide. Nature Communications. January 2017 http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14435

U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization International Plant Protection Convention. 2012. International Standards for Phytosanitary Meaures No. 36 Integrated Measures for Plants for planting. Rome. Online at https://www.ippc.int/ Accessed December 7, 2012.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and Forest Service, 2000. Pest Risk Assessment for Importation of Solid Wood Packing Materials into the United States.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2009. Proposed Rule Importation of plants for planting: establishing a category of plants for planting not authorized for importation pending pest risk assessment. Federal Register 74(140): 36403-36414 July 23, 2009.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 7 CFR Parts 318, 319, 330, 340, 360, and 361. Federal Register Rules and Regulations Vol. 83, No. 53. Monday, March 19, 2018

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2014. Asian gypsy moth pest alert https://www.aphis.usda.gov/publications/plant_health/content/printable_version/fs_phasiangm.pdf and pers. comm.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2007. Pests and mitigations for manufactured wood décor and craft products from China for importation into the United States. Revision 6. July.

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2012. Importation of wooden handicrafts from China. Final rule. Federal Register 77(41): 12437-12444. March 1. Online at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-03-01/pdf/2012-4962.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2013.

United States Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Statistics Freight Facts and Figures

https://www.bts.dot.gov/sites/bts.dot.gov/files/docs/FFF_2017.pdf accessed 19/8/13

United States Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, U.S. Waterborne Foreign Container Trade by U.S. Customs Ports (2000 – 2017) Imports in Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units (TEUs) – Loaded Containers Only

at https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/freight_analysis/nat_freight_stats/docs/06factsfigures/fig2_9.htm

Williams, L.H. and J.P. La Fage. 1979. Quarantine of Insects Infesting Wood in International Commerce. in J.A. Rudinksy, ed. Forest Insect Survey and Control Fourth Edition 1979

Wu,Y., N.F. Trepanowski, J.J. Molongoski, P.F. Reagel, S.W. Lingafelter, H. Nadel1, S.W. Myers & A.M. Ray. 2017. Identification of wood-boring beetles (Cerambycidae and Buprestidae) intercepted in trade-associated solid wood packaging material using DNA barcoding and morphology Scientific Reports 7:40316