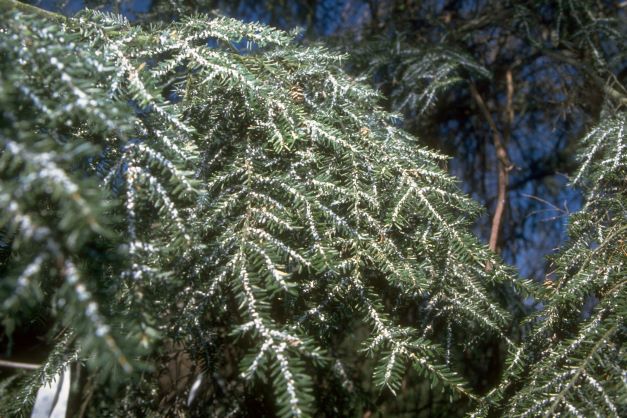

I blogged recently about North Carolina’s multi-pronged hemlock conservation program. As noted there, scientists are putting considerable hope in biological control as the most promising strategy to protect eastern (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina hemlocks (T. caroliniana) from the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA; Adelges tsugae). For a more detailed discussion of the adelgid’s life cycle, go here.

A new study by Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton (full citation at end of blog) cheers us by supporting the probable efficacy of this approach – as long as a complete suite of biocontrol agents is deployed. The study points to the need to introduce additional biocontrol agents, specifically those that feed in the summer.

The study analyzed the relative importance of two different mechanisms to protect plants from herbaceous insects: do some hemlock species have an enhanced ability to fend off the adelgid (bottom-up protection); or do predators apply sufficient pressure (top-down protection) to reduce adelgid populations to levels that the tree can withstand? The study simultaneously analyzed

(1) the relative importance of summer-active and winter-active native predators;

(2) whether HWA colonization and abundances differed on western and eastern hemlock species;

(3) the relative importance of top-down and bottom-up forces on HWA feeding on western and eastern hemlocks in the adelgid’s native range;

4) tested whether the adelgid is ubiquitous at low densities across the Pacific Northwest (PNW) and compared HWA abundance in PNW to invaded range in New England.

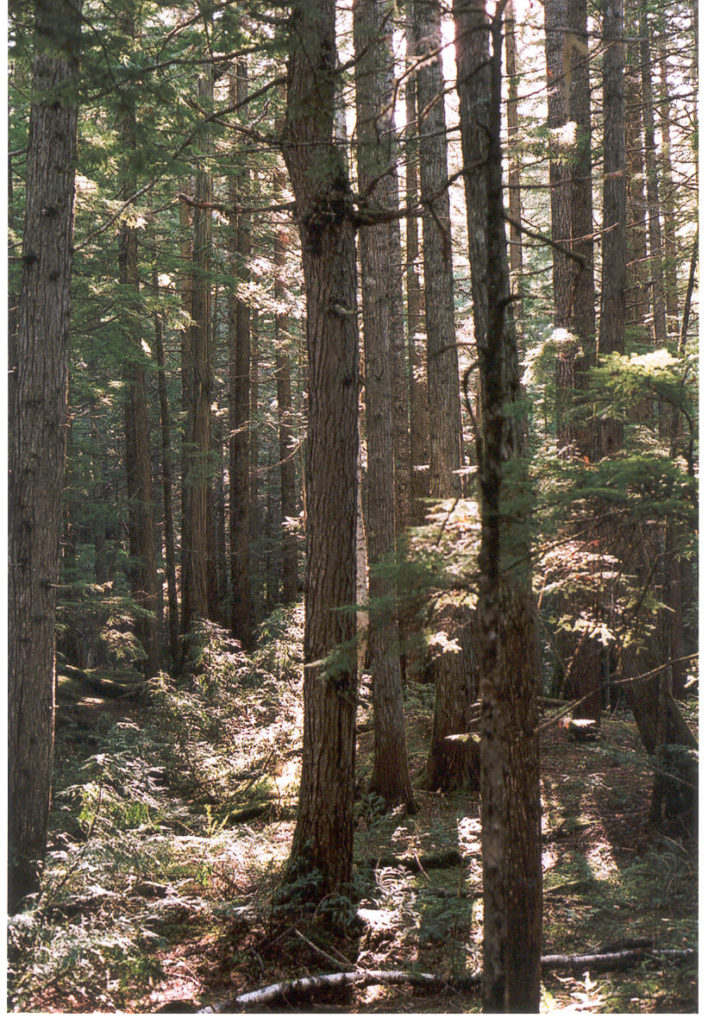

The study was carried out in Washington State, where both western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and HWA are native. They were able to compare adelgid impacts on eastern hemlock because the tree is planted in parks and gardens in the PNW.

In an earlier study, (Crandall et al. 2020) found that L. nigrinus was not able to reduce HWA densities in the east. Laricobius spp have their greatest impact on HWA by larval feeding on the progrediens eggs produced by the sistens. However, 90% of hatching progrediens die naturally because there are a finite number of needles for them to settle on. To have an impact on HWA populations, Laricobius spp would have to prey on more than 90% of progrediens eggs. The solution appears to be summer-active predators – e.g., silver flies — which feed on the progrediens eggs and the sistens eggs which the progrediens generation lays.

KEY FINDINGS

- Western hemlock is a native host of the adelgid. Crandall, Lombardo, and Elkinton found no evidence that western hemlock’s structure, chemistry, or other attributes help it fend off adelgid attack. The proportion of branches colonized by HWA was significantly higher on western than on eastern hemlock. Indeed, HWA populations were able to reach levels similar to those in eastern North America and were able to persist on western hemlock for multiple generations. Thus there is no evidence for bottom-up control of HWA on western hemlock.

- HWA survival was significantly lower on branches of western hemlock when predators were allowed access. Crandall assumes that the smaller, non-significant, decrease in HWA densities on eastern hemlocks in the Pacific Northwest is also attributable to predation, although the data are too few to support a definitive conclusion. These predators included a species that has been released as a biocontrol agent in the east, Laricobius nigrinus. More important, apparently, was the presence of summer-active predators, including Leucotaraxis spp. and generalists. These summer-active predators are active from the progrediens nymph stage in April through the aestivating sistens nymph stage until about October. Laricobius nigrinus doesn’t become active until September. These results support the hypothesis that predator-caused mortality is responsible for suppressing HWA during rare and localized outbreaks on western hemlock in the PNW. In the east there are no native natural enemies that attack HWA – which is introduced to the region.

- Effective control of HWA on the eastern naïve hosts will require establishment of a suite of predators which – together — attack the adelgid during both summer and winter.While several possible biocontrol agents have been introduced in the region, and at least some – e.g., Laricobius nigrinus – have established self-sustaining populations, are spreading, and have high predation rates, they have had very limited success in reducing HWA populations. Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton say these data support the recent decision by the USDA Forest Service to augment the HWA biocontrol effort by introducing two species of silver flies, Leucotaraxis argenticollis and Le. piniperda, that feed on both the sistens and progrediens generations in PNW.

- Tree-adelgid interactions are probably significantly affected by the lineage of both – whether the tree species has co-evolved with the specific lineage of the adelgid with which it is interacting. Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton think evaluation of any Tsuga species’ resistance to HWA or any potential biocontrol agent needs to be studied in relation to the appropriate lineage of the adelgid.

When they compared HWA abundance (in 2021) on hemlock forests in western Washington with HWA abundance at introduced HWA range in New England, Crandall, Lombardo and Elkinton found that HWA abundance was higher in New England. They note that these comparisons are between two different linages of HWA – the lineage native to PNW and the introduced Japanese lineage in the East.

The authors note that HWA densities in the PNW are higher at the urban site (Seattle) than rural sites. Perhaps the reason is lower densities of HWA predators in non-forest settings because some, e.g., La. nigrinus, require a duff layer for pupation. Duff layers are rarely permitted to accumulate in urban areas. The authors call for studies to assess the relative abundance and identify factors affecting the abundance of HWA predators in rural and urban settings.

SOURCES

Crandall R.S., Jubb C.S., Mayfield A.E., Thompson B., McAvoy T.J., Salom S.M. and J.S. Elkinton. 2020. Rebound of Adelges tsugae spring generation following predation on overwintering generation ovisacs by the introduced predator Laricobius nigrinus in the eastern United States. Biological Control 145, 104-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104264

Crandall, R.S., J.A. Lombardo, and J.S. Elkinton. 2022. Top-down regulation of hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) in its native range in the Pacific Northwest of North America. Oecologia 199, 599-609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-022-05214-8

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or