Close to four hundred tree species native to the United States are at risk of extinction. The threats come mainly from non-native insects and diseases – a threat we know gets far too little funding, policy attention, and research.

As Murphy Westwood, Vice President of Science and Conservation at the Morton Arboretum, which led the U.S. portion of a major new study, said to Gabriel Popkin, writing for Science: “We have the technology and resources to shift the needle,” she says. “We can make a difference. We have to try.”

Staggering Numbers

More than 100 tree species native to the “lower 48” states are endangered (Carrero et al. 2022; full citation at the end of this blog). These data come from a global effort to evaluate tree species’ conservation status around the world. I reported on the global project and its U.S. component in September 2021. This month Christina Carrero and colleagues (full citation at the end of this blog) published a summary of the overall picture for the 881 “tree” species (including palms and some cacti and yuccas) native to the contiguous U.S. (the “lower 48”).

This study did not address tree species in Hawai`i or the U.S. Pacific and Caribbean territories. However, we know that another 241 Hawaiian tree species are imperiled (Megan Barstow, cited here).

Assessing Threats: IUCN, NatureServe, and CAPTURE

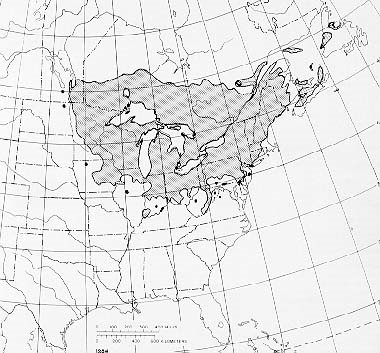

Carrero and colleagues assessed trees’ status by applying methods developed by IUCN and NatureServe. (See the article for descriptions of these methods.) These two systems consider all types of threats. Meanwhile, three years ago Forest Service scientists assessed the specific impacts of non-native insects and pathogens on tree species in the “lower 48” states and Alaska in “Project CAPTURE” (Conservation Assessment and Prioritization of Forest Trees Under Risk of Extirpation). All three systems propose priorities for conservation efforts. For CAPTURE’s, go here.

Analyses carried out under all three systems (IUCN, NatureServe, and CAPTURE) concur that large numbers of tree species are imperiled. Both IUCN and CAPTURE agree that non-native insects and pathogens are a major cause of that endangerment. While the overall number of threatened species remained about the same for all three systems, NatureServe rated threats much lower for many of the tree species that IUCN and CAPTURE considered most imperiled.

This difference arises from the criteria used to rate a species as at risk. IUCN’s Criterion A is reduction in population size. Under this criterion, even extremely widespread and abundant species can qualify as threatened if the population declines by at least 30% over three generations in the past, present, and/or projected future. NatureServe’s assessment takes into account rapid population decline, but also considers other factors, for example, range size, number of occurrences, and total population size. As a result, widespread taxa are less likely to be placed in “at risk” categories in NatureServe’s system.

In my view, the IUCN criteria better reflect our experience with expanding threats from introduced pests. Chestnut blight, white pine blister rust, dogwood anthracnose, emerald ash borer, laurel wilt disease, beech leaf disease, and other examples all show how rapidly introduced pathogens and insects can spread throughout their hosts’ ranges. (All these pests are profiled here . ) They can change a species’ conservation status within decades whether that host is widespread or not.

Which Species Are at Risk: IUCN

Carrero and colleagues found that under both IUCN and NatureServe criteria, 11% to 16% of the 881 species native to the “lower 48” states are endangered. Another five species are possibly extinct in the wild. Four of the extinct species are hawthorns (Crataegus); the fifth is the Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha) from Georgia. A single specimen of a sixth species, an oak native to Texas (Quercus tardifolia),was recently re-discovered in Big Bend National Park.

The oak and hawthorn genera each has more than 80 species. Relying on the IUCN process, Carrero and colleagues found that a significant number of these are at risk: 17 oaks (20% of all species in the genus); 29 hawthorns (34.5% percent). A similar proportion of species in the fir (Abies), birch (Betula), and walnut (Juglans) genera are also threatened.

Other genera have an even higher proportion of their species under threat, per the IUCN process:

- all species in five tree genera, including Persea (redbay, swampbay) and Torreya (yews);

- two-thirds of chestnuts and chinkapins (Castanea), and cypress (Cupressus);

- almost half (46.7%) of ash trees (Fraxinus).

Pines are less threatened as a group, with 15% of species under threat. However, some of these pines are keystone species in their ecosystems, for example the whitebark pine of high western mountains.

Carrero et al. conclude that the principal threats to these tree species are problematic and invasive species; climate change and severe weather; modifications of natural systems; and overharvest (especially logging). Non-native insects and pathogens threaten about 40 species already ranked by the IUCN criteria as being at risk and another 100 species that are not so ranked. Climate change is threatening about 90 species overall.

Considering the invasive species threat, Carrero and colleagues cite specifically ash trees and the bays (Persea spp.). In only 30 years, the emerald ash borer has put five of 14 ash species at risk. All these species are widespread, so they are unlikely to be threatened by other, more localized, causes. In about 20 years, laurel wilt disease threatens to cause extinction of all U.S. tree species in the Persea genus.

Carrero and colleagues note that conservation and restoration of a country’s trees and native forests are extremely important in achieving other conservation goals, including mitigating climate change, regulating water cycles, removing pollutants from the air, and supporting human well-being. They note also forests’ economic importance.

As I noted above, USFS scientists’ “Project CAPTURE” also identified species that deserve immediate conservation efforts.

Where Risk Assessments Diverge

All three systems for assessing risks agree about the severe threat to narrowly endemic Florida torreya and Carolina hemlock.

With three risk ranking systems, all can agree (as above), all can disagree, or pairs can agree in four different ways. Groups of trees fall into each pair, with various degrees of divergence. Generally, only two of the three systems agree on more widespread species:

- black ash: IUCN and Project CAPTURE prioritize this species. NatureServe ranked it as “secure” (G5) as recently as 2016.

- whitebark pine: considered endangered by IUCN, “vulnerable” (G3) by NatureServe. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed listing the species as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act. https://www.fws.gov/species-publication-action/endangered-and-threatened-wildlife-and-plants-threatened-species-18 However, Project CAPTURE does not include it among its highest priorities for conservation. Perhaps this is because there are significant resistance breeding and restoration projects already under way.

- tanoak: considered secure by both IUCN and NatureServe, but prioritized by Project CAPTURE for protection.

Carrero notes the divergence between IUCN and NatureServe regarding ashes. Four species ranked “apparently secure” (G4) by NatureServe (Carolina, pumpkin, white, and green ash) are all considered vulnerable by IUCN. They are also prioritized by Project CAPTURE. I have described the impact of the emerald ash borer on black ash. Deborah McCullough, noted expert on ash status after invasion by the emerald ash borer, also objects to designating this species as “secure” (pers. comm.).

This same divergence appears for eastern hemlock.

Port-Orford cedar is currently ranked as at risk by IUCN and Project CAPTURE, but not NatureServe. Growing success of the restoration breeding project has prompted IUCN to change the species’ rank from “vulnerable” to “near threatened”. IUCN is expected to reclassify it as of “least concern” in about a decade if breeding efforts continue to be successful (Sniezko presentation to POC restoration webinar February 2022).

While these differing detailed assessments are puzzling, the main points are clear: several hundred of America’s tree species (including many in Hawai`i, which – after all – is our 50th state!) are endangered and current conservation and restoration efforts are inadequate.

Furthermore, a tree species loses its function in the ecosystem long before it becomes extinct. It might still be quite numerous throughout its range – but if each individual has shrunken in size it cannot provide the same ecosystem services. Think of thickets of beech root sprouts – they cannot provide the bounteous nut crops and nesting cavities so important to wildlife. Extinction is the extreme. We should act to conserve species much earlier.

YOU CAN HELP!

Congress is considering the next Farm Bill – which is due to be adopted in 2023. Despite its title, this legislation has often provided authorization and funding for forest conservation (for example, the US Forest Service’ Landscape Scale Restoration Program).

There is already a bill in the House of Representatives aimed at improving the US Department of Agriculture’s prevention and early detection/rapid response programs for invasive pests. Also, it would greatly enhance efforts to restore decimated tree species via resistance breeding, biocontrol, and other strategies. This bill is H.R. 1389.

The bill was introduced by Rep. Peter Welch of Vermont, who has been a solid ally and led on this issue for several years. As of August 2022, the bill has seven cosponsors, most from the Northeast: Rep. Mike Thompson [CA], Rep. Chellie Pingree [ME], Reps. Ann M. Kuster and Chris Pappas [NH], Rep. Elise Stefanik [NY], Rep. Deborah K. Ross [NC], Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick [PA].

Please write your Representative and Senators. Urge them to seek incorporation of H.R. 1389 in the 2023 Farm Bill. Also, ask them to become co-sponsors for the House or Senate bills. (Members of the key House and Senate Committees are listed below, along with supporting organizations and other details.)

Details of the Proposed Legislation

The Invasive Species Prevention and Forest Restoration Act [H.R. 1389]

- Expands USDA APHIS’ access to emergency funding to combat invasive species when existing federal funds are insufficient and broadens the range of actives that these funds can support.

- Establishes a grant program to support research on resistance breeding, biocontrol, and other methods to counter tree-killing introduced insects and pathogens.

- Establishes a second grant program to support application of promising research findings from the first grant program, that is, entities that will grow large numbers of pest-resistant propagules, plant them in forests – and care for them so they survive and thrive.

- [A successful restoration program requires both early-stage research to identify strategies and other scientists and institutions who can apply that learning; see how the fit together here.]

- Mandates a study to identify actions needed to overcome the lack of centralization and prioritization of non-native insect and pathogen research and response within the federal government, and develop national strategies for saving tree species.

Incorporating the provisions of H.R. 1389 into the 2023 Farm Bill would boost USDA’s efforts to counter bioinvasion. As Carrera and colleagues and the Morton Arboretum study on which their paper is based demonstrate, our tree species desperately need stronger policies and more generous funding. Federal and state measures to prevent more non-native pathogen and insect pest introductions – and the funding to support this work – have been insufficient for years. New tree-killing pests continue to enter the country and make that deficit larger –see beech leaf disease here. Those here, spread – see emerald ash borer to Oregon.

For example, funding for the USDA Forest Service Forest Health Protection program has been cut by about 50%; funding for USFS Research projects that target 10 high-profile non-native pests has been cut by about 70%.

H.R. 1389 is endorsed by several organizations in the Northeast: Audubon Vermont, the Maine Woodland Owners Association, Massachusetts Forest Alliance, The Nature Conservancy Vermont, the New Hampshire Timberland Owners Association, Vermont Woodlands Association, and the Pennsylvania Forestry Association.

Also, major forest-related national organizations support the bill: The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF), American Forest Foundation, The Association of Consulting Foresters (ACF), Center for Invasive Species Prevention, Ecological Society of America, Entomological Society of America, National Alliance of Forest Owners (NAFO), National Association of State Foresters (NASF), National Woodland Owners Association (NWOA), North American Invasive Species Management Association (NAISMA), Reduce Risk from Invasive Species Coalition, The Society of American Foresters (SAF).

HOUSE AND SENATE AGRICULTURE COMMITTEE MEMBERS – BY STATE

| STATE | Member, House Committee | Member, Senate Committee | Key members * committee leadership # forestry subcommittee leadership @ cosponsor of H.R. 1389 |

| Alabama | Barry Moore | ||

| Arizona | Tom O’Halleran | ||

| Arkansas | Rick Crawford | John Boozman* | |

| California | Jim Costa Salud Carbajal Ro Khanna Lou Correa Josh Harder Jimmie Panetta Doug LaMalfa | ||

| Colorado | Michael Bennet # | ||

| Connecticut | Jahana Hayes | ||

| Florida | Al Lawson Kat Cammack | ||

| Georgia | David Scott * Sanford Bishop Austin Scott Rick Allen | Raphael Warnock Tommy Tuberville | |

| Illinois | Bobby Rush Cheri Bustos Rodney Davis Mary Miller | Richard Durbin | Note that the report was led by scientists at the Morton Arboretum – in Illinois! |

| Indiana | Jim Baird | Mike Braun | |

| Iowa | Cindy Axne Randy Feenstra | Joni Ernst Charles Grassley | |

| Kansas | Sharice Davids Tracey Mann | Roger Marshall# | |

| Kentucky | Mitch McConnell | ||

| Maine | Chellie Pingree @ | ||

| Massachusetts | Jim McGovern | ||

| Michigan | Debbie Stabenow * | ||

| Minnesota | Angie Craig Michelle Fischbach | Amy Klobuchar Tina Smith | |

| Mississippi | Trent Kelly | Cindy Hyde-Smith | |

| Missouri | Vicky Hartzler | ||

| Nebraska | Don Bacon | Deb Fischer | |

| New Hampshire | Ann McLane Kuster @ | ||

| New Jersey | Cory Booker | ||

| New Mexico | Ben Ray Lujan | ||

| New York | Sean Patrick Maloney Chris Jacobs | Kristen Gillibrand | |

| North Carolina | Alma Adams David Rouzer | ||

| North Dakota | John Hoeven | ||

| Ohio | Shontel Brown Marcy Kaptur Troy Balderson | Sherrod Brown | |

| Pennsylvania | Glenn Thompson | ||

| South Dakota | Dusty Johnson | John Thune | |

| Tennessee | Scott DesJarlais | ||

| Texas | Michael Cloud Mayra Flores | ||

| Vermont | Patrick Leahy | ||

| Virginia | Abigail Spanberger # | ||

| Washington | Kim Schreir |

SOURCES

Christina Carrero, et al. Data sharing for conservation: A standardized checklist of US native tree species and threat assessments to prioritize and coordinate action. Plants People Planet. 2022;1–17. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/ppp3

Washington Post: Sarah Kaplan, “As many as one in six U.S. tree species is threatened with extinction” https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/08/23/extinct-tree-species-sequoias/

Popkin, G. “Up to 135 tree species face extinction—and just eight enjoy federal protection”, Science August 25, 2022. https://www.science.org/content/article/135-u-s-tree-species-face-extinction-and-just-eight-enjoy-federal-protection

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or

Posted by Faith Campbell

We welcome comments that supplement or correct factual information, suggest new approaches, or promote thoughtful consideration. We post comments that disagree with us — but not those we judge to be not civil or inflammatory.

For a detailed discussion of the policies and practices that have allowed these pests to enter and spread – and that do not promote effective restoration strategies – review the Fading Forests report at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm

or