Guest blog by Lewis Ziska, Associate Professor, Environmental Health Sciences at the Columbia University

[Dr. Ziska has spent his career analyzing the impacts of CO2 and climate change on plants – and therefore on people. He served as Project Leader for global climate change at the International Rice Research Institute; then spent 24 years at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, where he worked primarily on documenting the impact of climate change and rising carbon dioxide levels on: Crop selection improves production; Climate and agronomic pests, including chemical management; Climate, plant biology and public health impacts on food security with a focus on nutrition and pesticide use.]

No question you’ve heard the term, “Climate Change” or “Global Warming”, or my personal favorite, “Global Weirding”. The consequences are talked and discussed in the media—as they should be—but often the media, like many Americans, is focus challenged. Or in more polite terms, they have the attention span of a hummingbird on crack. Which is to say, that simple physical consequences, like sea level rise (heat melts ice!), and stranded animals on ice (Poor polar bear!), or intense storms (newscaster whipped about in the rain, yelling to be understood) are repeated, over and over again. Understandable, makes for good TV.

But it also makes you feel separate from what is happening, these consequences of climate change are to the “other”. I don’t live near the ocean, I don’t interact with polar bears; sure we have storms, but I live in the Midwest, in one of those states that begins with a vowel. Shoot, I commute to work, try and make ends meet, I’m not some damn tree hugger. Why should I care?

To understand why, you need a bit more background, some science that isn’t always available on TV or social media when it comes to global weirding.

First, while you may not be a tree hugger, you do, in fact, interact with nature. Several times. Every day. We call those times, “breakfast”, “lunch” and “dinner”.

You depend on nature for food. And clothing. And paper. And medicine. And oxygen. And construction materials (wood), and many, many other things. So, if nature gets hinky, and the climate becomes uncertain, it might be worth your while to think about climate change, or global weirding, in a different light. What I want to do here then, is to illuminate two examples that I hope will help you see why climate could affect you, directly and significantly.

Let’s begin with plants. Those green living things that comprise the bulk of the natural world (literally, if you were to weigh the natural world, 97% would be plants, 3% animals). Then let’s look at them through two different lenses—how will climate weirding alter your food; shoot, how will it alter the air that I breathe?

Let’s start with a basic food, rice. Obviously you don’t want to mess with its production, or its nutritional quality. But that is exactly what global weirding is doing.

Rice has flowers. Not big showy ones, but flowers none the less—ones that get fertilized with pollen, and seed is produced. The seed that feeds some two billion people– or about a quarter of the earth’s population.

Like all living things, plants are heat sensitive, and for rice, and many crop plants, the degree of sensitivity varies, depending on the part of the plant in question. Take a look at the table. The crops that are listed, including rice, are the core of what the world eats. Now notice the difference in temperature sensitivity. Vegetative parts of the plant, leaves and stems, are reasonably tolerant of higher temperatures, but flowers are not. Pollen, the plant equivalent of animal sperm, is highly temperature sensitive, and if the temperatures get into the high 90s (37-38oC), they become deformed, and the rice plant doesn’t produce seeds. Same for a number of plants, ones necessary to feed 8 billion people.

| Crop | Opt. Temp. Vegetative | Opt. Temp. Flowering | Failure Temp. Flowering |

| Maize | 28-35oC | 18-22oC | 35oC |

| Soybean | 25-37oC | 22-24oC | 39oC |

| Wheat | 20-30oC | 15oC | 34oC |

| Rice | 28-35oC | 23-26oC | 36oC |

| Sorghum | 26-34oC | 25oC | 35oC |

| Cotton | 34oC | 25-26oC | 35oC |

| Peanut | 31-35oC | 20-26oC | 39oC |

Data are adapted from Hatfield et al., 2011.

Doubtful you’ve seen this climate threat to the global food supply on TV or a streaming service. I caught a glimpse once of temperature and agriculture on a CNN newscast, but with the “expert” calmly stating that we would just have to grow our corn in Canada, ha-ha. (Somehow, at least for rice, it’s hard to imagine India, one of the world’s largest rice producers, moving its rice production northward to the Himalaya’s, but I digress.)

Food is fundamental. If production, especially that of a global staple like rice, is impacted by rising temperatures there will be consequences. Rising prices, reduced availability, and wide-spread hunger.

But there is more to consider. Given the global dependence on rice, any change in its nutritional quality will also have effects, especially on poorer countries that rely heavily on rice as a major food source. And here we need to delve a little deeper into another aspect of climate weirding that doesn’t make it to the popular media—that rising carbon dioxide (CO2), the primary greenhouse gas, can also directly influence plant nutrition. The reasons are complicated, but in simple terms all living things consist of elements, carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, sulfur, copper, etc., etc. A plant gets it’s carbon from the air (CO2), but everything else (nitrogen, potassium) from the soil.

And there is an imbalance. In the last 50 years, atmospheric CO2 has increased by about 30%, and is projected to increase another 50% by the end of the century. With more CO2, plants are becoming carbon rich, but nutrient poor. Nutrient poor, because while CO2 has increased in the air, nutrients in the soil have not kept pace. A perverse carb loading at the plant level.

As a consequence, rice, and many other plants, are shifting their chemistry. For example, there is a general decline in protein, in part because protein requires nitrogen. There are similar ubiquitous declines in iron and zinc, important micro-nutrients needed for human development.

Such nutritional degradation is of obvious global importance, and does, on occasion, show up on basic media when warming / weirding is mentioned, but you’d be hard pressed to find it.

Let’s move our light to another hidden bit of science. How plants can influence the air we breathe.

As humans, we like to trade things. And a large percentage of what we trade are living organisms, from fish to trees. But what began as local, regionalized trading has grown with the global population and the needs of that population—a population of 1.6 billion at the beginning of the 20th century is now ~8 billion at the beginning of the 21st. And we haven’t stopped trading. Biological trade is not inherently bad, but it represents a historically unprecedented global movement of DNA across continents, across countries, regions, towns, cities and ecosystems. And some of the DNA, when introduced, can do great harm to the environment, the economy and to human health. That harm has a name, “Invasive Species”.

Let us focus on one such plant species introduced to Eastern Europe, one that almost every American has personal experience (ACHOO!) come fall. The species is common ragweed. An invasive plant whose introduction and spread in Eastern Europe—introduced accidently through imported seeds or contaminated hay – has resulted in enormous environmental and economic losses in agriculture and public health in recent decades. In Hungary, the most important ambient biological air pollutant is: ragweed.

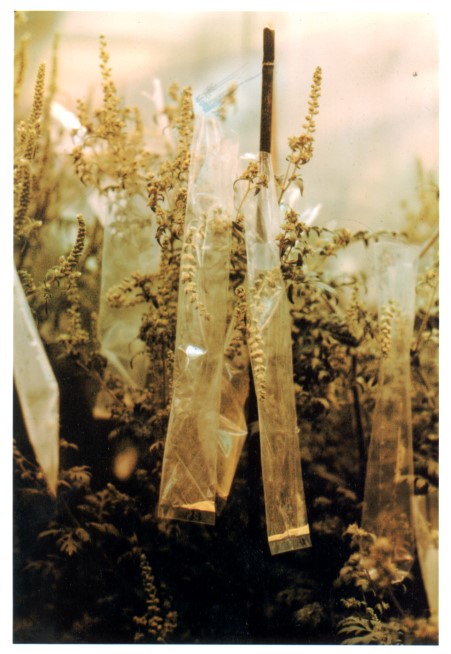

The photo is from studies that I led looking at how ragweed pollen would respond to temperature and carbon dioxide. (If you’re curious, ragweed likes both.) Warmer temperatures, earlier Springs, later Autumns can extend its pollen season; not only extend, but increase the amount of pollen being generated. There is even some data suggesting that rising CO2 can alter pollen chemistry, making it more allergenic (REFS). Sadly, ragweed pollen doesn’t appear as temperature sensitive as that of rice, or other agricultural plants.

I wish I could say that ragweed was the exception among allergenic plants, but it’s the rule. Parthenium weed is a highly invasive species that has spread to more than 40 countries around the world. Like ragweed its pollen are highly allergenic, but it can also produce severe rashes, like poison ivy, and is known to be poisonous to livestock. It is highly aggressive, and arriving in a new location (where it has no natural enemies) can dominate landscapes, reducing biodiversity. And as with ragweed, high temperatures, longer growing seasons, heatwaves and droughts are expanding its range, and for that matter, make controlling its spread more difficult.

Such responses among invasive species will have direct impacts on air quality, especially among those (myself included) who suffer from seasonal allergies. Gasping for air is never fun.

Estimates are that pollen and seasonal asthma affects more than 24 million of us, including 6 million kids. And yet, when watching news reports of climate change, how many times have you seen a report on pollen and air quality? On increasing allergies or asthma? Once? Twice?

I could go on, (and if you need more examples, read “Greenhouse Planet”, my latest book). But my point is this: Not all of the consequences of rising carbon dioxide and climate change, warming, weirding, whatever, make for “good” TV. There is so much more to explore. So, do yourself a favor. Take a deeper dive, find out what is happening behind the scenes.

Because if we are going to rise to the challenge, we need to know what we are fighting against. Right now, the media is exemplary on showing some things, but silent on much else of importance. Watching news coverage of climate change is a bystander watching a cataclysm, and thinking, “Boy, glad I’m not experiencing THAT!”. Yet in the simplest and most basic of terms, you are, or will be, affected– from food choices to nutrition, even your allergies. And so much more.

It isn’t just about polar bears. It’s about you. Read, Understand, Act.

Now.